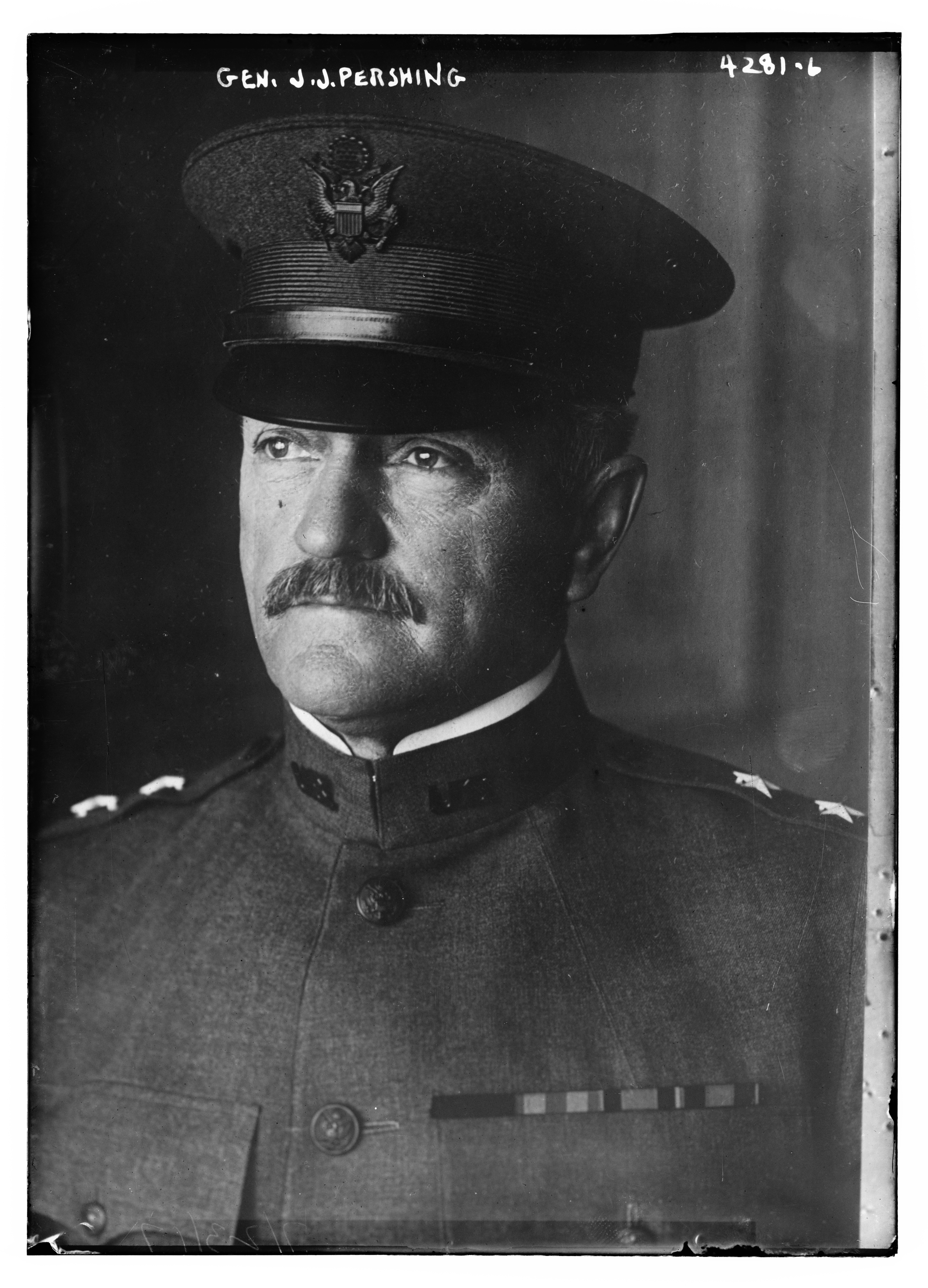

General John J. Pershing was commander of the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front in World War I.

(Credit: Regimental Historian & Archivist)

No. 2

General Pershing and his JAG

The Friendship that Helped Win WWI

By Major Robert W. Runyans

You will assume without a moment’s hesitation that I have both your professional and personal interests at heart in everything that I suggest. Our uninterrupted friendship has extended over too many years to permit me any other view.1 – Major General Enoch H. Crowder.

Professionally [Crowder’s] exceptional record speaks for itself more eloquently than anything I could say. I had a high regard for him, both as a man and an officer.2 – General of the Armies John J. Pershing

I. Introduction

Thirty-five miles separate the northwestern Missouri towns of Edinburg and Laclede.3 Although never particularly populous, and located over 4,500 miles from the Western Front in France,4 this small geographic area retains distinction for the 1859 and 1860 birthplaces of Major General (MG) Enoch H. Crowder and General of the Armies (GEN) John J. Pershing.5

Pershing, the more heralded of the two men, needs little introduction and features prominently in any study of U.S. involvement in World War I. His command of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF)—then, the largest American command in history6—fought alongside British and French forces to achieve the final defeat of imperial Germany.7 Of lesser acclaim, but well-known to judge advocates, is fellow Missourian Enoch H. Crowder.8 Serving as the Judge Advocate General (tJAG)9 and Provost Marshal General throughout the conflict,10 MG Crowder’s duties as a “swivel chair”11 general included drafting and implementing the Selective Service Act,12 which provided seventy-two percent of the AEF’s manpower.13 To succinctly state each man’s signature contribution to victory in World War I: one led the army that the other raised.

Considering the symbiotic relationship between these major achievements, it is fitting that these officers also enjoyed a long personal relationship that preceded and followed their wartime association. Marked by a voluminous exchange of letters, their personal relationship began as a friendship between Missourians with similar biographies, matured into a professional association between officers that decisively contributed to victory in World War I, and concluded as the two aging lawyers14 attempted to steward the Judge Advocate General’s Department.15 In recognition of the 100th anniversary of the Armistice, it is especially appropriate now to celebrate and study this relationship. As illuminated by their correspondence and actions, it remains an ideal example of a judge advocate supporting an operational commander and a sterling illustration of brotherhood in the profession of arms.

II. Origins

Relationships are built, in part, from mutual interests and common experiences. Against these criteria, even the most superficial examination of Pershing and Crowder’s biographies reveals that they had both. As native Missourians born at the advent of the Civil War,16 each served as a secondary school instructor before winning acceptance to, and attending, the U.S. Military Academy.17 There, although their attendance did not overlap, each performed fairly well academically,18 and commissioned into the cavalry.19 Following commissioning, both men would serve on the closing American frontier,20 participate in final actions against the Apache and Sioux,21 and become professors of military science at midwestern universities.22 Their careers would also take them abroad, with service in Cuba,23 the Philippines,24 and as observers in the Russo-Japanese War.25 Each would also see Europe during the pre-war era, as both men toured that continent separately for professional purposes.26 As noted, Pershing—in addition to Crowder27—also found time to earn a law degree.28

Of all these similar experiences, two stand out as being particularly important in their friendship. First, and most interesting to judge advocates, was their mutual interest in the legal profession that dominated most of their initial, surviving correspondence.29 From 1910 to 1917, almost every letter discussed an array of legal topics, including judge advocate assignments,30 proposed changes to the Articles of War,31 prison reform,32 and academic thoughts on the charge of desertion.33 With letters sent to and from such exotic locations as the Philippines’ Moro Province34 and the mysterious location of “Headquarters Punitive Expedition, U.S. Army, Somewhere in Mexico,”35 the very existence of this correspondence underscores both their mutual interest in the law and the value each placed on his relationship with the other.

Second, if legal matters formed the quantitative bulk of their early correspondence, it was their shared Missouri heritage that likely played a larger qualitative role in their friendship. As geographic bonds remain a common fixture of friendships between service members, Pershing and Crowder’s frequent references to hometown July 4th celebrations,36 remarks on mutual friends,37 and plans for joint visits38 probably mirror correspondence still common among all ranks today, albeit via different media. Further, the fact that such references often accompanied requests for the other to “write to me oftener”39 or the transatlantic lament of “I wish you and I could have a talk,”40 provides additional evidence of this bond’s weight. Reflecting the true importance of Missouri in their friendship, Pershing likely captured it best in a curious letter of recommendation to Crowder concerning another officer who was “possibly just a little bit different from other people,”41 but still “a Missourian.”42

Most important, considering their later wartime roles, their Missouri bond also contained a temporal component in addition to mere geographic coincidence. In one letter to Crowder, Pershing described tJAG as a “red-blooded American from Northwestern Missouri,”43 who—like him—was “born amid the active scenes of conflict.”44 Given each man’s families’ experiences during the Civil War,45 these “active scenes of conflict”46 may have animated the pair further, as both men cited certain failures of the federal government in the Civil War as reasons for their joint support of universal conscription in World War I.47 Writing on the topic, Crowder probably spoke for Pershing when he stated that “[t]he relics of the past and our childhood recollections themselves often exercise a directing force in the shaping of our points of view and our activities.”48 Ultimately, the U.S. experience with universal conscription would unite them as strongly professionally as their Missouri roots and shared interest in the law did personally.

III. The War Years

In addition to uniting Crowder and Pershing around a common idea, universal conscription served as the catalyst that layered a professional association on top of their personal friendship. With war looming, President Wilson tasked Crowder to draft the Selective Service Act (the “Act”)49 on February 4, 1917.50 Efficiently completing a draft for Congress on 5 February 1917,51 tJAG was then appropriately dual-hatted as Provost Marshall General—with the charge to administer the Act’s apparatus—on 28 May 1917,52 ten days after the Act’s passage53 and in the same month that Pershing was selected as the American Expeditionary Forces’s (AEF) commander and sailed for France.54 Given these new roles, Pershing’s success as a combat commander was directly tied to Crowder’s success as Provost Marshall General.

To fully appreciate this new professional nexus between the two friends, it is important to consider the strategic situation in 1917. With an ill-equipped and inexperienced force formed from a total U.S. Army of less than 120,000 active Soldiers,55 Pershing was surrounded by hardened allies accustomed to casualties in excess of 300,000 in single operations like Verdun in 1916.56 With such carnage being routine since 1914, the pressure for Pershing to contribute quickly to the Allied effort by subordinating his smaller Army to the command of British and French officers was both heavy and understandable.57 Resisting this pressure, Pershing refused to commit to such an arrangement and stuck firm to the idea that he would command American forces, in an American sector, while conducting American offenses.58 This position rankled the British and French, and resulted in diplomatic pressure on President Wilson to intervene.59 Thus, Pershing’s position could only hold if he received the necessary manpower.

Crowder understood Pershing’s predicament. While tJAG certainly wanted to succeed as a matter of professional duty, he also privately assured his friend that “you need never contemplate a failure”60 and that “I am completely absorbed in the work of the draft . . . so as to give you assurances that the flow of man-power to the cantonments and thence to the battle-field shall not be interrupted.”61 These assurances probably helped to assuage Pershing’s private concern that “Americans—have got the burden of this thing on our shoulders”62 and his urging to Crowder that “the armies we shall need should be called out without delay.”63 In his private response to Pershing’s concerns, Crowder made perfectly clear his position, stating that Pershing should “consider me as working in elbow-touch with you and in subordinate relations to your great work, with no desire on my part quite so strong as to see you succeed in every way.”64

Beyond these words of encouragement, Crowder also got results. During his administration of the Act, Crowder provided 2,758,54265 of the “doughboys”66 that composed a U.S. force of approximately 3.5 million.67 When considering universal conscription began with the Act’s passage in May 1917,68 and that the armistice was signed on 11 November 1918,69 the staggering scale of this accomplishment cannot be overstated. With these results, Pershing became secure in his separate station and led the AEF in operations such as the Meuse-Argonne offensive, where the weight of American participation finally overcame the will of Germany to continue their effort.70 Reflecting pride in their joint contributions to this result, Crowder wrote candidly in their personal correspondence that “as I am raising the Army and you are fighting it, none of the other States of the Union are doing much.”71 Needless to say, such a frank assessment would have been inappropriate for official communications.

Befitting their friendship, Pershing also recognized the importance of Crowder’s duties and took care to encourage him. Understanding that Crowder was self-conscious about his stateside status,72 Pershing wrote that “I need not say that to have you here would give me the greatest pleasure . . . I honesty and candidly think that your work there, and your presence there close to the Secretary, are far more valuable.”73 Discouraging Crowder from further efforts at a combat role might have also been an additional act of mercy, as Pershing had no issue with dismissing officers he found ill-suited to combat duty despite long-associations.74

Further, Pershing was also correct about the importance of Crowder’s proximity to the Secretary of War. As a member of the “War Council,”75 Crowder became privy to official AEF communications sent to other departments.76 From this perch, Crowder offered Pershing candid assessments and provided insight into the bureaucracy’s inefficiency. For example, noting that not all of Pershing’s requests for material had been met, Crowder convinced the War Department to make a special survey of AEF’s communications and identify the deficiencies.77 As he explained to Pershing, “I pointed out that it was not fair to charge you with a hundred percent of performance unless you were given a hundred per cent of compliance.”78 Being very responsive to Pershing’s invitation “to write to you as illuminatingly as I can about conditions on this side,”79 Crowder carried this further and advocated for Pershing at the highest levels of the War Department.80 In his varied roles, Crowder thus supplied Pershing’s army as a matter of professional duty, provided protection to his friend’s political flank in D.C., and enabled an outlet for candid conversations during a fraught time. Few relationships have accomplished so much during war.

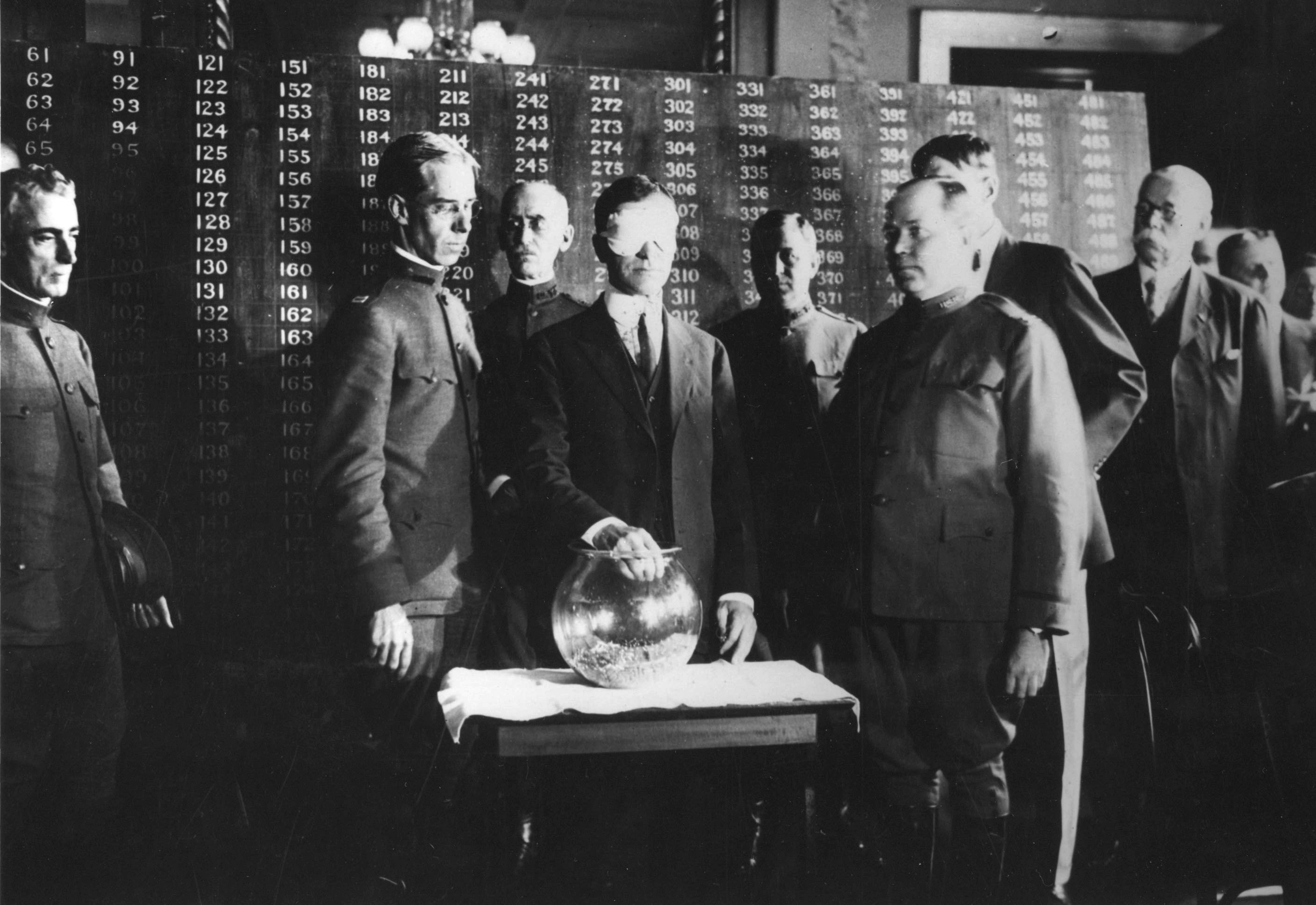

“...and the number is 246...” Photograph shows the drawing of the first number for the Second Draft of men to serve in the U.S. Army during World War I. Shown in the image is Secretary of War Newton D. Baker picking the first capsule out of the bowl. Left-to-right: Captain Charles R. Morris, Major General Enoch Crowder, and Secretary of War Baker. (Photo Credit: USAMHI)

IV. Later Years

It is worth noting that Crowder and Pershing’s relationship endured a rocky period following the war. Given his dual-hatted responsibilities during World War I, significant portions of Crowder’s legal duties fell to a subordinate, Brigadier General Samuel Ansell.81 For various reasons, rooted in both professional judgments and personal animosity, the two men collided in a very public debate over the fairness of the military justice system, the system’s balance of discipline and justice, and the role of commanders in the process.82 Crowder was ultimately vindicated in the public spectacle, but he carried a bitterness about the affair and towards those who he felt were less than absolutely loyal.83 Although Pershing did not side against Crowder, and provided support in his correspondence,84 Crowder felt that Pershing was insufficiently supportive given his rank and fame.85

Viewed another way, whatever hard feelings Crowder harbored about the experience, he overcame them with regard to Pershing. Following the war, the two continued their frequent correspondence, shifting from discussions about their wartime duties and resuming their old conversations about Missouri86 and the legal profession—especially judge advocate assignments.87 In addition to lower-level assignments, their correspondence soon focused on the appointment of future tJAGs.

This new focus was due, in large part, to the pair’s final accolades at the end of their long careers. Pershing, returning from France a hero, was appointed to the congressionally created rank of “General of the Armies” in 191988 and served as Chief of Staff until 1924.89 Crowder was also reappointed to a third four-year term as the Judge Advocate General on 18 February 1919,90 but again was dual-hatted for much of this term as an envoy to Cuba.91

With Crowder’s retirement looming, and with the wounds of the “Ansell-affair” still fresh, tJAG succession was a natural topic of conversation.

With three candidates identified, Pershing—as Chief of Staff—repeatedly sought Crowder’s advice on the selection of judge advocates Walter Bethel, Edward Kreger, or John Hull.92 Pershing stated his preference for Bethel, who previously served as the AEF’s judge advocate.93 Crowder expressed a contrary preference for Edward Kreger, calling him “unquestionably the best lawyer in the Department.”94 Further offering his candid thoughts, Crowder also provided what must rank among the ultimate “third-file” comments made by a tJAG to an Army Chief of Staff. Recalling that Bethel “years-ago”95 failed to complete a revision of Winthrop’s Unabridged Military Law96 while assigned to West Point, Crowder conceded that the “Department will be safe and thoroughly efficient”97 under Bethel’s guidance, while offering faint praise of his “high average . . . performance.”98 While Pershing would push back on Crowder’s characterization of Bethel,99 and initially offered his own criticisms of Kreger,100 there is no record that he challenged Crowder’s exceptionally harsh criticism of Hull: “Hull never decided a legal question except by throwing dice. He is not a lawyer and never will be one . . . ”101

Ultimately, MG Bethel became tJAG during Pershing’s tenure as Chief of Staff and served from 1923–1924.102 MG Kreger also achieved this position, after later winning Pershing’s confidence and respect,103 and served from 1928–1931.104 Despite Crowder’s criticism, MG Hull occupied the office between the favored successors.105

Franklin Bell (1856–1919), left, a U.S. Army officer, shakes hands with Brigadier General Enoch Crowder (1859–1932), at Camp Upton, a U.S. Army installation in Yaphank, New York, during World War I (Credit: Flickr Commons project, 2015).

V. Conclusion

Although ultimately anticlimactic, this discussion of future tJAGs is important for several reasons beyond its showcase of extreme candor and hints of palace intrigue. As their correspondence soon shifted to more nostalgic topics and inevitable concerns for poor health,106 this marked one of the last, truly substantive discussions between the two leaders. Reflective of the extraordinary trust and rapport between the two men, it underscores how remarkable it was that their relationship developed these qualities primarily through written communication.107 Although few judge advocates can expect to share so many common experiences and mutual interests with their commander-clients, the relationship between Pershing and Crowder remains a reminder to all professionals that diligent effort put forward to establish rapport and trust can pay great dividends.108

Second, this final discussion is also reflective of their shared concern for the institutions that each served for over thirty-five years.109 Capturing this concept, Crowder wrote to Pershing that “[t]he time is growing all too short in which we can be fair to subordinates who have served faithfully and honestly, and with great efficiency.”110 Although referring directly to Kreger’s candidacy, Crowder’s statement evoked their larger professional obligation to steward the profession and develop a future Army.111 Speaking volumes about each man as a professional and leader, their mutual concern for institutions is an excellent reminder to current members of the profession of arms about obligations to an enduring organization.

Beyond stewardship, Crowder’s support to Pershing is also particularly instructive for today’s judge advocates. To quote a bit of doctrine:

No matter the level of command to which assigned, judge advocates have several roles. They are counselors, advocates, and trusted advisors to commanders and Soldiers. They are Soldiers, leaders, and subject matter experts in all of the core legal disciplines. In every aspect of their professional lives, judge advocates serve the Army and the Nation with their expertise, dedication, and selflessness.112

In each of these roles, it is undebatable that Crowder performed remarkably well. Although his greatest contribution occurred in non-legal role, his expert legal mind drafted the Act that enabled Pershing’s success as a combat leader. Possessing a tireless work-ethic,113 Crowder’s dedication to implementing the Act then ensured that Pershing received the necessary manpower. As an advocate for his friend in France, Crowder was also invaluable in his stateside role as a conduit for information and counsel. Most of all, as a trusted advisor, his frequent communications marked by sage advice and candor stands unique in history with respect to the practice of law. He rightfully deserves to be remembered as the “Greatest Judge Advocate in History,”114 and he remains the ultimate example of expert support, across varied roles, to an operational commander.

Naturally, Crowder should not receive all the credit. As shown in their correspondence, credit for the critical rapport developed between these men also belongs to Pershing. From the tinder of their common experiences, both made efforts to communicate with each other over the decades and across vast distances. Considering their joint roles in creating their relationship, and considering the extraordinary benefits for the nation that it provided, Pershing and Crowder’s association should inspire not only legal professionals, but all Soldiers engaged in the defense of this nation. The U.S. Army values the importance of teamwork at every level to accomplish its mission. Here was an example of such teamwork and comradeship under the stress of world war. It succeeded brilliantly. TAL

MAJ Runyans is a Litigation Attorney for the Environmental Law Division, U.S. Army Legal Services Agency, Fort Belvoir, Virginia.

Notes

1. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Aug. 18, 1917) (on file with the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, John J. Pershing Papers, General Correspondence, Box 56 [hereinafter Pershing Papers]). The correspondence between Pershing and Crowder dates from April 17, 1910 to February 10, 1932.

2. David A. Lockmiller, Enoch H. Crowder: Soldier, Lawyer, and Statesman 261 (1955). In the only book-length biography of Crowder, Lockmiller quotes a letter received from Pershing. The letter is dated May 28, 1940. Id.

3. Distance from Edinburg, Mo. to Laclede, Mo., Google Maps, http://maps.google.com (follow the “Get Directions” hyperlink; then search for “Edinburg, Mo.” and “Laclede, Mo.”; then right click on the map location for “Edinburg” and select “Measure Distance”; then click on the map location for “Laclede”).

4. Distance from Edinburg, Mo. to Verdun, France, Google Maps, http://maps.google.com (follow the “Get Directions” hyperlink; then search for “Edinburg, Mo” and “Verdun, France”; then right click on the map location for “Edinburg” and select “Measure Distance”; then click on the map location for “Verdun”). Verdun is used as an example of the location of the Western Front in World War I. See, e.g., Robert A. Doughty et al., Warfare in the Western World: Military Operations Since 1871 523–633 (1996).

5. See Lockmiller, supra note 32, at 13–21 (discussing Crowder’s childhood); Gene Smith, Until the Last Trumpet Sounds: The Life of General of the Armies John J. Pershing 3–15 (1998) (discussing the early life of General Pershing).

6. Compare James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom 306–07 (1988) (citing other scholarship and concluding that approximately 2.1 million Soldiers served in the Union Army), with Enoch H. Crowder, The Spirit of Selective Service 363 (1920) (noting that approximately 3.5 million men were serving in the U.S. military on Nov. 11, 1918). See also I.C.B. Dear et al., The Oxford Companion to World War II 1192–1198 (1995) (indicating a U.S. Army strength of over 8.1 million on Mar. 31, 1945 and exclusive of approximately 4 million additional service members in the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps).

7. Mitchell Yockelson, Forty-Seven Days 320 (2016). Yockelson discusses the U.S. Army’s performance in the Meuse-Argonne offensive of 1918, and argues that it was the “deciding factor” in the war. Id. See also Doughty et al., supra note 5, at 624–33 (discussing U.S. participation in the reduction of the St. Mihiel Salient and the Meuse-Argonne offensive in 1918). Id.

8. See Fred L. Borch, The Greatest Judge Advocate in History? The Extraordinary Life of Major General Enoch H. Crowder (1859–1932), Army Law., May 2012. See also Joshua E. Kastenburg, to Raise and Discipline an Army 7–12 (2017). (discussing the lack of study of judge advocates during World War I and commenting that Pershing is the only U.S. leader from that conflict to receive significant study).

9. Id. Borch, supra note 9, at 3. The author notes that the office now referred to as “The Judge Advocate General” was referred to as “the Judge Advocate General” until 1924. Id.

10. War Dep’t, Biographical Data on Major General Enoch H. Crowder (1932) (on file with the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, John J. Pershing Papers, General Correspondence, Box 56) [hereinafter War Dep’t]; U.S. Military Academy, The Register of Graduates and Former Cadets 2879 (2010) [hereinafter Register]. See Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 133-216; Borch, supra note 9, at 4.

11. Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 148 (stating that “Crowder was preeminently a swivel chair general and for him the law was truly a jealous mistress.”). Id. “Swivel chair general” was a derogatory reference to officers serving in Washington D.C. during World War I. Id. at 192. Crowder’s status was part of the reason that he turned down the possibility of promotion to Lieutenant General. See Lockmiller, supra, at 191–92. Of note, Kastenberg claims that Crowder was also offered a fourth star after the Armistice. Kastenberg, supra note 89, at 352.

12. Selective Service Act, ch. 15, 40 Stat. 76 (1917) (codified as amended at 50 U.S.C. §201).

13. David Stevenson, With Our Backs to the Wall 146 (2011).

14. See, e.g., Smith, supra note 56, at 44 (noting that Pershing received a law degree while serving as a professor of military science at the Univ. of Nebraska).

15. Kastenberg, supra note 89, at 5. Kastenberg notes that this term referred to the staff department supervising all judge advocates.

16. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 17; Smith, supra note 6, at 4.

17. Id. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 22; Smith, supra note 56, at 12-14. Pershing also indicated that he previously turned down an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy. John J. Pershing, My Life Before the World War, 1860-1917: A Memoir 36 (John T. Greenwood ed., 2013) [hereinafter Before the World War]. This publication is an edited compilation of Pershing’s draft, unpublished memoir. The editor notes that the original papers are located in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Before the World War, supra, at Editor’s Note.

18. U.S. Military Academy, Official Register of the Officers and Cadets of the United States Military Academy 10 (1881), available at http://digital-library.usma.edu/cdm/compound object/collection/ p16919coll3/id/2081/show/2063/rec/9 [hereinafter USMA 1881]; U.S. Military Academy, Official Register of the Officers and Cadets of the United States Military Academy 10 (1886), available at http://digital-library.usma.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16919coll3/id/2300/rec/69 [hereinafter USMA 1886]. The 1881 publication notes that Crowder graduated thirty-first out of class of fifty-four cadets. In contrast to his high marks in law, Crowder received the fifth most demerits in his graduating class. USMA Records 1881, supra, at 10. The 1886 edition notes that Pershing graduated thirtieth in a class of seventy-seven and ranked thirteenth in discipline. USMA Records 1886, supra, at 10. Pershing also served as First Captain of the U.S. Corps of Cadets. In response to this accolade, Pershing is quoted as saying that “[n]o other military promotion has ever come to me quite equal to that.” Smith, supra note 6, at 23. See also David R. Hughes, The Class of 1881, It’s Great 75th Year, Assembly, July 1936, at 12–16, available at http://digital-library.usma.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/ assembly/id/7594/rec/26. This article, published by the U.S. Military Academy’s alumni organization, states that “the two most widely known members of the class were Colonel Andrew S. Rowan and Major General Enoch Crowder.” Id. at 16. As a matter of curiosity, the article further notes that Rowan “became a legend for his carrying of the ‘Message to Garcia.’” Id.

19. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 33; Register, supra note 101, at 3179.

20. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 34–65; Smith, supra note 56, at 27-38.

21. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 93; Smith, supra note 56, at 32, 37–38.

22. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 38–49; Smith, supra note 56, at 39–45.

23. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 109–20; Smith, supra note 56, at 51–55.

24. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 66–85; Smith, supra note 26, 95–118.

25. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, 98–108; Smith, supra note 56, at 85–91.

26. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 130–31; Smith, supra note 56, at 101–04.

27. See, e.g., Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 44.

28. See, e.g., Smith, supra note 53, at 44.

29. See, e.g., Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Apr. 17, 1910) (Pershing Papers). This letter is particularly interesting because it concerns the assignment of Captain Samuel Ansell to Pershing’s command in the Philippines. In this letter, Crowder states that Ansell is “abreast” of “the best men in the service.” Id. Pershing concurred in Crowder’s assessment, responding that “I consider him an exceptional man.” Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Aug. 19, 1910) (Pershing Papers). A decade later, Crowder and Ansell would have a very public dispute over military justice reform that would involve the credibility of the Judge Advocate General’s Department. Kastenberg, supra note 89, at 352–407.

30. See, e.g., Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Sept. 11, 1916) (Pershing Papers). In this 14-page letter, Crowder listed his thoughts on forty-two candidates for appointment as judge advocates. See also Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jun. 8, 1911) (Pershing Papers). Congratulating Crowder on his selection as the Judge Advocate General (tJAG), Pershing stated – without context – that “[t]his department has been allowed to lag behind. It has not kept up with the general progress that has been made in other departments.” Id.

31. See, e.g., Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Sep. 19, 1916) (Pershing Papers).

32. See, e.g., Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Mar. 30, 1915) (Pershing Papers).

33. See, e.g., Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Apr. 5, 1915) (Pershing Papers).

34. See, e.g., Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Aug. 19, 1910) (Pershing Papers).

35. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jun. 15, 1916) (Pershing Papers). This letter is further revealing of Pershing’s rapport with Crowder. In addition to discussing the legal work of a mutual acquaintance, Pershing reveals his private frustration with the pursuit of Pancho Villa and states that “[t]he whole situation is pathetic.” Id.

36. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jul. 22, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

37. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Dec. 17, 1921) (Pershing Papers).

38. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Oct. 15, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

39. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jun. 28, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

40. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jul. 22, 1918) (Pershing Papers). See also Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Feb. 10, 1919) (Pershing Papers) (stating that “[t]here is a great deal you and I would talk about if we could have a meeting but which, if I undertook to write about it would not look well on paper.”). Id.

41. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Oct. 24, 1919) (Pershing Papers).

42. Id. See also Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 21. Lockmiller notes that “a sure password to his [Crowder’s] inner office was: ‘I’m a friend from Grundy County, Missouri.’” Id.

43. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jun. 28, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

44. Id.

45. Among other observations, Pershing notes that his “earliest recollection” was of an 1864 raid on Laclede that killed a man named David Crowder (unknown relation). Before the World War, supra note 187, at 16-17. Pershing’s father was also a target of that raid. Smith, supra note 56, at 5. Crowder’s father served in the Union Army and his namesake uncle was killed in action. Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 19–20.

46. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jun. 28, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

47. See Crowder, supra note 67, at 76-91; John. J. Pershing, My Experiences in the World War 21–22 (1920). Pershing relates that he convinced Texas officials to support the idea of universal conscription in 1917 and states that “[i]t was very important that a repetition of the experience in the Civil War should be avoided. Id. at 21. Pershing also goes on to praise Crowder’s work in preparing the Selective Service Act and administering the draft. Id. at 27. Of note, Pershing’s autobiography also won the Pulitzer Prize. John J. Pershing, The 1932 Pulitzer Prize Winner in History, The Pulitzer Prizes, http://www.pulitzer.org/winners/ john-j-pershing (last visited Jun. 18, 2018). Crowder wrote extensively on the failures of conscription and volunteering in The Spirit of Selective Service. See Crowder, supra note 67, at 76–91.

48. Crowder, supra note 7, at 94 (1920); Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 19. Lockmiller dismisses the notion that Crowder was influenced by his childhood experiences during the Civil War and states that “[t]here is little to substantiate this thesis, and Enoch Crowder, who was six years old when the war ended, never claimed to have been thus influenced.” Id. Although it is impossible to know Crowder’s personal motivations, he specifically discussed failures of federal government policy and its resulting violence during the Civil War as justification for World War I’s system of universal conscription in The Spirit of Selective Service. See generally Crowder, supra note 7, at 76–91.

49. Selective Service Act, ch. 15, 40 Stat. 76 (1917) (codified as amended at 50 U.S.C. §201).

50. Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 152–55.

51. Id.

52. War Dep’t, supra note 101, at 2.

53. Selective Service Act, ch. 15, 40 Stat. 76 (1917) (codified as amended at 50 U.S.C. §201).

54. Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 163; Pershing, supra note 48, at 45.

55. Stevenson, supra note 134, at 247. Additionally, there were 164,000 National Guard troops available in April 1917. Id.

56. Doughty et al., supra note 54, at 573. Reflecting the carnage of that battle and the general condition of the war’s combat, the German’s referred to it as a “sausage grinder.” Id.

57. Smith, supra note 6, at 157. See also Stevenson, supra note 14, at 247. The issue was “amalgamation” of U.S. forces into British and French commands. Id.

58. Pershing, supra note 48, at 42–43. Pershing noted the instructions he received from the Secretary of War on May 26, 1917: “you are directed to cooperate with the forces of the other countries employed…but in so doing the underlying idea must be kept in view that the forces of the United States are a separate and distinct component of the combined forces, the identity of which must be preserved.” Id. at 42. See Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War 202 (1973); Russell F. Weigley, History of the United States Army 381–382 (1984) [hereinafter History] (stating that “Pershing’s insistence that the American soldier must fight in an American army is generally accounted one of his principle achievements.”). Id. at 382.

59. See C.J. Bernardo & Eugene H. Bacon, American Military Policy: Its Development Since 1775, 354 (1957); Doughty et al., supra note 5, at 603.

60. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Oct. 15, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

61. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Aug. 29, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

62. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jun. 28, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

63. Id.

64. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jul. 22, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

65. Crowder, supra note 7, at 363.

66. “Doughboys” was the general slang for infantry Soldiers in World War I. See e.g., Willis R. Skillman, The A.E.F., Who They Were, What They Did, How They Did It 62 (1920).

67. Id. at 363.

68. See Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 166-68. Registration began on Jun. 5, 1917 and the first lottery occurred on Jul. 20, 1917.

69. History, supra note 59, at 395.

70. Yockelson, supra note 8, at 320; History, supra note 59, at 393. In History, the author states that “[w]hen the Americans continued to arrive in mounting numbers and continued to go into battle…German calculations were so upset that the high command went into a funk from which it never emerged, except to importune the civil government to make peace.” Id.

71. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Aug. 29, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

72. Crowder sought a combat command and was disappointed that he was not given a division in France. See Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 190. Crowder expressed this displeasure in multiple letters to Pershing, stating that “[r]emember Pershing, it is a hell of a thing to go through a war in which our Country is engaged, especially this World War, without getting shot at.” Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Feb. 25, 1918) (Pershing Papers). Among other comments, Crowder also stated that “I hate to think that it can be said that I have been efficient in the means of selecting other men to be shot at and equally efficient in not finding duty where I was not likely to be shot at myself.” Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing, (Jan. 19, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

73. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jun. 28, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

74. Smith, supra note 6, at 162.

75. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jan. 19, 1918) (Pershing Papers). Crowder describes the creation of this Council during a late-night meeting with the Secretary of War. Id.

76. Id.

77. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jan. 19, 1918) (Pershing Papers). Crowder states that he argued over several meetings “to analyze all the correspondence with you since you first set foot on foreign soil and see how many unsatisfied requisitions for men and material you had made.” Id.

78. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jan. 19, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

79. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jul. 22, 1918) (Pershing Papers).

80. See, e.g., id. Crowder recognized that he had a close relationship with the Secretary of War. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jan. 19, 1918) (Pershing Papers). In addition, Crowder also had a close relationship with many politicians, due to the role of tJAG during his service. Kastenberg, supra note 9, at 8–9. This included Pershing’s father-in-law, Senator Francis E. Warren. Kastenberg, supra note 9, at 396. See Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Feb. 10, 1919) (Pershing Papers). In one instance, this relationship served to notify Pershing of General Peyton March’s attempt to curtail Pershing’s command authority. Kastenberg, supra note 9, at 396. Of note, Crowder had an especially contentious relationship with March. Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 260. Informed that March’s gravesite in Arlington would be along a hillside next to his, Crowder is quoted as saying that “[w]e must locate another lot. I’ll be damned if I have that old S-O-B- looking downing on me throughout eternity.” Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 260.

81. Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 202.

82. See Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 200–16; Kastenberg, supra note 9, at 352–407; Borch, supra note 9, at 4. There is also speculation that Ansell’s motives were not entirely pure, as Ansell believed that Crowder would not return to the Judge Advocate General’s office after being appointed the Provost Marshall General. Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 202-03.

83. See, e.g., Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jan. 18, 1923) (Pershing Papers). In this letter, Crowder refers to the Ansell affair and points to an isolated incident when Bethel failed to confront an unnamed critic of Crowder. Crowder stated dismissively that Bethel “did not regard it as a matter of sufficient importance to give the offender a proper lesson in loyalty and decency.” Id.

84. Letter from John J. Pershing, U.S. Army, to Enoch H. Crowder, (Apr. 19, 1919) (Pershing Papers). Pershing states that “[t]he Ansell affair and consequent investigation shows complete failure to appreciate war condition by those who are airing their views. Perhaps when some of the fighting men get home they shall be able to help you out.” Id. See Lockmiller, supra note 3, at 215.

85. Kastenberg, supra note 9, at 402.

86. See, e.g., Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Dec. 17, 1921) (Pershing Papers). Pershing and Crowder visited the Univ. of Missouri together as honored guests at commencement on Apr. 21, 1920. Pershing Arrives at 1:40 P.M. Tomorrow, City to Greet A.E.F. Leader and Crowder, The Evening Missourian, April 20, 1920. Reporting on the joint visit, the local newspaper referred to the pair as “Missouri’s two foremost sons.” All Columbia Out to See Pershing and E.H. Crowder, The Evening Missourian, Apr. 21, 1920. During the visit, the two lawyers were also awarded honorary Doctorate of Laws degrees. Pershing Awarded LL.D. By University, The Evening Missourian, Apr. 22, 1920.

87. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Sep. 3, 1921) (Pershing Papers).

88. Register, supra note 101, at 3179; Smith, supra note 56, at 228.

89. Register, supra note 101, at 3179; Smith, supra note 56, at 253-56

90. War Dep’t, supra note 101, at 2.

91. Lockmiller, supra note 23, at 219, 231. See also Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Feb. 18, 1920) (Pershing Papers). In a reversal of their wartime situations, Crowder writes from the U.S.S. Minnesota and expresses his appreciation for Pershing’s correspondence, noting that “I am necessarily out of touch with affairs at home.” Id.

92. Based on Crowder and Pershing’s correspondence, Kreger and Bethel were the clear frontrunners. See, e.g., Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Sep. 3, 1921) (Pershing Papers). Hull’s candidacy appears to have been the result of Hull maneuvering himself into consideration through his relationship with Pershing’s assistant, General Habbord. See Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jul. 18, 1921) (Pershing Papers); Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Nov. 24, 1922) (Pershing Papers) (stating that “if Hull is appointed Judge Advocate General, the army will have the poorest lawyer and the best politician.”). See also Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Dec. 28, 1926) (Pershing Papers) (stating that “[f]or some reason General Habbord took a fancy to Hull.”). Id.

93. See, e.g., Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Sep. 3, 1921) (Pershing Papers). Pershing states that “my own selection, if it were left to me, would be General Bethel.” Id.

94. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jan. 18, 1923) (Pershing Papers).

95. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jan. 18, 1923) (Pershing Papers).

96. Crowder most likely refers to the 1886 publication. See William W. Winthrop, Military Law (1886).

97. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Jan. 18, 1923) (Pershing Papers).

98. Id.

99. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Jan. 13, 1922) (Pershing Papers). Pershing states that “I regret that Bethel’s claim could not have received a little bit stronger backing from you.” Id.

100. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Sept. 3. 1921) (Pershing Papers).

101. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Dec. 28, 1926) (Pershing Papers).

102. The Judge Advocate General’s Corps, Regimental History, https://www.jagcnet2.army.mil/sites/history.nsf/ homeContent.xsp?open&documentId=2CA917451330519E852580200070FA92 (last visited Jun. 18, 2018) [hereinafter Regimental History].

103. Letter from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Dec. 22, 1926) (Pershing Papers).

104. Regimental History, supra note 1023.

105. Regimental History, supra note 1023.

106. See, e.g., Telegram from John J. Pershing to Enoch H. Crowder (Feb. 10, 1932) (Pershing Papers).

107. Charles N. Pede, Communication is Key – Tips for the Judge Advocate, Staff Officer and Leader, Army Law., June 2016, at 4, 5.

108. Id.

109. Register, supra note 101, at 2879, 3179.

110. Letter from Enoch H. Crowder to John J. Pershing (Sep. 28, 1926) (Pershing Papers).

111. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 6-22, Army Leadership para. 35 (1 Aug. 2012); U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 1, The Army para 2-8 (17 Sep. 2012).

112. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Field Manual 1-04, Legal Support to the Operational Army para. 1-12 (18 Mar. 2013).

113. Crowder’s work ethic is frequent reference for his biographers. Even in his obituary, he was praised for his “capacity for incessant work.” Major General F.J. Kernan, Enoch H. Crowder, Sixty-Third Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy 122 (1932) available at http://digital-library.usma.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/aogreunion/id/19934/show/19684/ rec/69.

114. Borch, supra note 98, at 1.