A Soldier holds an American flag prior to the start of an oath of citizenship ceremony at Fort Knox, Kentucky. (Credit: Eric Pilgrim)

Practice Notes

Defending Your MAVNI Client

Security Clearance Revocations and Separations

By Captain Vy T. Nguyen

Your client tells you their commander is involuntarily initiating separation proceedings against them and they are worried this can lead to them being removed from the United States. They entered the Service through the Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest (MAVNI) program, have served for almost one year on active duty, and have not yet naturalized. Your client hands you a small, four-page packet from the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff (DCS) G-1, notifying them that the Department of Defense (DoD) Consolidated Adjudication Facility (CAF) has rendered an adverse Military Service Suitability Recommendation (MSSR) against them. Attached to the memorandum is an Acknowledgment of Notice and Election sheet and an unclassified summary of the Counterintelligence (CI)-Screening Interview and screening assessment. The screening assessment is one paragraph, finding your client has foreign ties to their family members, which poses a concern that cannot be mitigated. Nothing else follows. What do you do?

MAVNI Program Background

Between 2008 and 2016, 10,400 individuals enlisted in the U.S. military through the MAVNI program.1 At its inception in 2008, the MAVNI program aimed to recruit certain legally-present aliens whose skills are vital to the national interest.2 Those skills include high-demand, low-density skills such as medical specialties and expertise in certain languages.3 In return, MAVNI applicants are offered an expedited path to U.S. citizenship.

Given the tension between the program’s strategic goals and its security concerns, MAVNI recruits now face volatile consequences.

Eventually, “MAVNIs” encapsulated a group of recruits with diverse backgrounds and unique circumstances. At the time of enlistment, applicants were either asylees, refugees, holders of Temporary Protected Status, beneficiaries of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, or in another nonimmigrant category.4

The program also allowed administrative waivers for certain applicants

who lost their legal status but who were otherwise eligible for

enlistment under the MAVNI program.5 For these applicants, it also imposed a complementary requirement for the Service to ensure they obtained Deferred Action from the Department of Homeland Security.

As concerns grew over whether these foreign-born recruits posed an increased security concern, the program became more restrictive.6 In 2016, the DoD established new security screening requirements.7 It imposed a yearly cap on the number of enlistments per military department and an annual reporting requirement to Congress.8 Although the program was suspended in 2017, and resumed in 2018, the DoD is reportedly not accepting new applicants to the MAVNI program.9 Notably, parts of these restrictions have been successfully challenged in civilian courts.10

Given the tension between the program’s strategic goals and its security concerns, MAVNI recruits now face volatile consequences. Legal practitioners struggle to choose between pursuing recourse through the civilian judicial system and recourse through regular security clearance channels.11

Ultimately, representing a MAVNI client requires familiarity with CI processes, administrative separation procedures, and immigration law. When I was a newly commissioned judge advocate (JA) starting my first duty position as a legal assistance attorney, I didn’t even know what I didn’t yet know. Now, after tumultuous experiences with my own MAVNI clients, I at least know what I wish I had known when I met my first MAVNI client. So, whether you are a first-term JA or first-time MAVNI counsel, this article seeks to assist you in the early stages of responding to security concerns.

What Makes a MAVNI Client Different

Any Service member can face security clearance denial, suspension, or revocation, but a separate process exists for MAVNIs. Ordinarily, Service members facing security revocation will receive a notice of intent to revoke their security clearance from the DoD CAF containing a statement of reasons for the action. The MAVNI Service members receive an MSSR from DoD CAF where the immediate reasons for their separation are contained in a summarized CI statement. It may seem like a mere difference of nomenclature; but, in practice, the MAVNI process is complicated by frequent ad hoc policy changes, a lack of transparency, and varying standards based on the individual who applied it and the time at which it was applied.

Moreover, the length of time for MAVNIs to respond before they are removed from Service will depend on their duty status. For example, if your client is in the Reserve or National Guard, they will have the opportunity to respond directly to the DCS G-1 before the DCS G-1 issues a Military Service Suitability Determination (MSSD). Their chain of command will only be directed to initiate separation proceedings in accordance with Army Regulation (AR) 135-18 after your client receives an adverse MSSD.12 In contrast, if your client is on active duty, the DCS G-1 memorandum will direct their chain of command to initiate separation within thirty days of your client’s signed acknowledgment and election sheet. Your client’s only opportunity to respond to the MSSR will be through that separation process. And then—if your client is afforded the opportunity to respond—hopefully, they have not already declined that opportunity before coming to see you.

To top it off, there are high-stake immigration consequences. For instance, your MAVNI client has either not yet naturalized and is foremost concerned about their continued eligibility for naturalization; or, they were already naturalized and are concerned about their continued employment and/or denaturalization. Either type of MAVNI client can fall out of legal status. Therefore, both can face removal from the United States.

Your Ten-Point Checklist

1. Apply a Critical Eye to the Underlying Information

When you first read the DCS G-1 packet, do not take the information at face value. After all, a lot has happened in your client’s clearance adjudications process up to this point.13

Prior to shipping to basic training or serving any time on active duty,

each MAVNI applicant completed security screening requirements,

including 1) the National Intelligence Agency Check (NIAC), 2) the

CI-Screening Interview, and 3) Tier 3 or Tier 5 background

investigations and/or polygraphs, as applicable. Your client will have

also submitted a Standard Form (SF) 86,

Questionnaire for National Security Positions. The CI-Security Interview will be based on the findings of the NIAC,

review of the SF-86, and standard questions from the Service and DoD

CAF. These findings will be forwarded to the DoD CAF to support the

National Security Determination (NSD). The DoD CAF will also have

rendered the NSD based on thirteen National Adjudicative

Guidelines.14

The NSD/MSSR/MSSD process has changed over the years, in part due to judicial challenges. This includes the right for your MAVNI client to 1) receive notice of a negative determination, which was only required by policy beginning in 201815 and 2) to not undergo continuous monitoring, a requirement that otherwise was compulsory only from those who possessed the highest clearance levels.16 As a result, expect the amount and quality of information you receive for each client to vary.

Furthermore, the MAVNI program is an interdepartmental, interagency effort, so it is essential for you to know the “how” and “to whom” when submitting a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.17 To that end, your first task should be to draft and submit three FOIA requests: one for the CI-Screening from the U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command; another for any final reports, recommendations, or adjudicative decisions made by DoD CAF; and a third for your client’s SF-86 from the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency.18 If your client kept a copy of their SF-86, it could save you a lot of time. Otherwise, prepare for a potentially lengthy wait for FOIA request results.19 Though you can submit a request for expedited review in certain circumstances, at the outset of a separation proceeding, request an additional thirty to forty-five days to allow for the expected receipt of FOIA request results.

2. Get to Know Your Client’s Circumstances

Your legal strategy must account for the potential impact on your client’s retention and immigration status. Some questions to consider include: Does your client want to stay in the Service and are they inside their reenlistment window? Your client would have a vested interest in expeditious processing through the command channel. What is your client’s current legal status? If it looks like they will lose their permanent residency, advise them to consult an immigration attorney sooner rather than later. Did they commit a past immigration violation, intentionally or unwittingly? This could increase their chances of removal from the United States and, as their attorney, you should make them aware. Could their responses to the security clearance concerns reveal that past violation and subject them to immigration proceedings? Regardless of the answers to these questions, you should review their responses for incriminating statements. Keep in mind that these are just some of the things for you to issue-spot as you work with your MAVNI client.

Talk to your client and draw out their narrative summary. Ask questions such as: What does your client remember about the interview? What was their English language skill level at the time of the interview versus now? That four-page packet your MAVNI client initially hands you likely only contained a single-paragraph summary of a CI agent’s impression of them at a time when they might not have spoken English well.

3. Help Your Client Respond

Once the FOIA results return, advise your client to write a pointed response addressing why each concern in the CI-Summary is either wrong or can be mitigated. All Service members are evaluated against thirteen National Adjudicative Guidelines which assess their reliability, loyalty, and trustworthiness to include: Allegiance to the United States, Foreign Influence, and Foreign Preference.20

Each Guideline lists example conditions that could mitigate the security concern. For example, “Guideline B: Foreign Influence” is concerned with foreign contacts and interests which could result in divided allegiance.21 So, contact with foreign family members can create a concern if that contact creates a heightened risk of foreign exploitation, inducement, manipulation, pressure, or coercion.22 This concern may be mitigated in the following circumstance: if the nature of the relationship, the country in which these persons are located, or positions or activities of those persons in that country are such that it is unlikely the individual will be placed in a position of having to choose between the interests of a foreign entity and the interests of the United States.23

The CI-Screening will include a narrative question and answer and the screener’s conclusions. After reading the CI-Summary, what does the client think could have triggered a security concern? Compare the narrative Q&A with the CI-Summary to determine the heart of the security concern(s). Advise your client to round out the facts about the circumstances underlying the security concern(s). Show them the guidelines and talk through evidence they could provide to explain, refute, mitigate, and/or correct the security concern(s). Focus their efforts on building a solid narrative statement and gathering letters of support. Edit for grammar and clarity, but try to preserve their voice.

4. Research

Based on your initial consultation and while you wait for FOIA results, compare how your client’s security concerns have been adjudicated in other cases. Look in JA community repositories, including JAGCNet and milSuite, to see if other JAs have dealt with a client in similar circumstances.24 For more nuanced issues, take advantage of public databases which track the latest immigration policy changes.25 Next, refer to the handbook for security clearance adjudicators to understand the criteria adjudicators must apply.26

Most importantly, scrub the DoD CAF and Defense Office of Hearings and

Appeals (DOHA) websites. The DOHA is an administrative office with

quasi-judicial powers to review security clearance appeals. While DOHA

decisions have no precedential value, reading through analogous

cases—such as those involving contractors—provide insight into the minds

of administrative law judges.27

Consider also how your local standard operating procedures could impact your client’s circumstances. For example, installation policy may require Soldiers to begin transition assistance programs in anticipation of initiating separation proceedings. Your MAVNI client should anticipate being removed from a meaningful position and ordered to attend classes about life after the military before they will have the opportunity to respond to the MSSR.

And then, if you have time—whether in an in-processing brief or through information papers—practice preventive law. By doing this, other MAVNIs who go through this revocation process can at least know they have somewhere to turn and then seek legal help before they potentially waive their right to respond.

5. Gather Support from Your Client’s Command Team

With your client’s permission, reach out to their chain of command. If their command wants to retain them, ask them to provide detailed letters of support that address their impression of your client’s reliability, loyalty, trustworthiness, and—if they know—the enumerated security concern(s). They should also emphasize your client’s value to the unit. Because CI interviews likely only lasted a few hours, and the summary is based on the impressions of a single screening officer, letters from the command team can carry significant weight. This is because the unit has spent far more time with them and is better positioned to know the Soldier.

When considering who to ask, consider those in a position of authority who could provide specific, objective assessments of their Soldier—whether it is their commander or a senior noncommissioned officer. If the individual providing a character reference is also an immigrant, see if their situation is analogous to your client’s experience and turned out favorably.28

6. Steward the Process

Commanders, staff sections, and JAs alike tend to shy away from anything

involving immigration. That, coupled with a process with which few have

any experience, creates bottlenecks and a general unwillingness of

responsible parties to take actions needed to process your client’s

paperwork efficiently. Consequently, it is critical you—as an advocate

for your MAVNI—be a good steward of the process.

One way to do this is to know where and through whom paperwork should be

transmitted. Once the separation authority signs your client’s

separation packet and forwards it through your client’s G-1 to the MAVNI

Operations Team, the packet undergoes a multi-step review process that

includes routing through the office of the Assistant Secretary of the

Army–Manpower and Reserve Affairs. Clients and JAs can send requests for

status updates to the MAVNI Operations Team general inquiries

mailbox.29 The MSSR memorandum should provide a point of contact, which may be either a specific person in the Enlisted Accessions Branch at HQDA or the MAVNI Operations Team general inquiries mailbox. If they are not aware of the steps to take, refer your client’s security manager(s) questions regarding interim security clearance eligibility to the DCS G-2, Personnel Security Branch. Follow up with the HQDA point(s) of contact, the commander, and/or the security manager(s).

Your job will be to ensure your client has received the complete separation packet and the paperwork is being transmitted in a timely manner. At the same time, be sure to manage your client’s expectations and prepare them for lengthy periods of time where they likely will not receive further answers.

7. Coordinate Early

Ideally, your legal strategy incorporates all stakeholders as early in the process as possible. You must know whether the Client Services office handles the whole process on your installation or whether Trial Defense Service (TDS) would be willing to be involved before the unit initiates separation proceedings. Once separation proceedings are initiated, does TDS handle the case exclusively? There are fewer worse experiences for a client than believing their chances slipped away due to a careless handoff or disjointed legal strategy. So, while it is impractical to provide joint representation for your MAVNI client, it is professional to convey a seamless transition between attorneys; and, it is critical that efforts are complementary.

So, your task will be to provide an explicit explanation of why your client does not pose a security concern by contrasting their enumerated security concern(s) and mitigating evidence against the DOHA decisions and adjudicator handbook.

You can view this Legal Assistance Office-TDS handoff and early coordination as analogous to the military justice advisor preparing a case in anticipation of court-martial and in close consultation with the litigators. Consider creating a joint, local standard operating procedure between the two sections, as this could alleviate some of the stress caused by an opaque security clearance process and also yield better results than ad hoc efforts whose success or failure rests on the motivation of the individual JA.

8. Build the Due Process Argument

As counsel, draft a memorandum that highlights the procedural difficulties your client faced. Advocate for them based on how their experience contravenes AR 635-200’s due process requirements.30 As previously mentioned, MAVNIs were not always entitled to receive notice of a negative determination, nor were they required to undergo continuous monitoring—even though their non-MAVNI counterparts did not receive notice of negative determination and were required to undergo continuous monitoring.

It may initially seem reasonable to require initiation of administrative separation in your client’s case, just as command teams would be required in other serious cases (e.g., drug abuse). But then you find the basis for your MAVNI client’s derogatory information—usually that they have foreign ties to their family members—cannot be mitigated. And you realize that a program which aimed to hire foreign-born recruits will, as a matter of course, find that recruit has foreign ties. The consequence of the program’s strategic goals and its post-facto security concerns are apparent. So, your task will be to provide an explicit explanation of why your client does not pose a security concern by contrasting their enumerated security concern(s) and mitigating evidence against the DOHA decisions and adjudicator handbook.

9. Manage Your Client’s Retention Expectations

Ensure your client is aware that, regardless of the outcome, a copy of the MSSR memorandum will be placed in their Army Military Human Resource Record. While this process is pending, a code will appear on their record brief that can prevent them from reenlisting. Although this can have the practical effect of a bar to reenlistment, the DD Form 214, Certificate of Release or Discharge from Active Duty, will not contain the same separation code.31

Clearly explain to your client that losing their military employment is

a possibility. Reassure them that you will help them through this

process to the best of your ability, but also encourage them to develop

a secondary course of action. Discuss their preferences for civilian

employment, including public service positions that will require similar

security checks.

10. Do Not Avoid Immigration Law

No one expects you to be an immigration expert simply because you are

representing a MAVNI client. But immigration consequences will be at the

forefront of their concerns. Just as you would research other areas of

law for your client, limited by your State rules of professional

responsibility, you should put forth the effort to understand the basic

framework of U.S. immigration laws and procedures.

Remember also that active duty Soldiers are afforded greater due process

than Reserve and National Guard Soldiers. After serving longer than 180

days, they cannot be separated with uncharacterized discharges. For

Reserve Soldiers, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service does not

treat an uncharacterized discharge as an honorable discharge, which

could affect the client’s eligibility for naturalization. Even those who

were naturalized may not be completely shielded; through a series of

subsequent events, denaturalization may be a possibility. For example,

if during their background investigation they were found to have

naturalized by illegally procuring citizenship or by concealment of a

material fact or by willful misrepresentation, naturalization may be

revoked.32 Naturalization through wartime military service may also be revoked if they are discharged under other than honorable conditions within a period or periods aggregating five years.33 For those without valid status, the Service is only obliged to ensure deferred action while the applicant is enrolled in the MAVNI program; therefore, out-of-status clients may face removal upon separation. In most circumstances, the U.S. immigration system is only easy for those with limitless time, money, and stability.

Nevertheless, recall that MAVNI recruits are a diverse population. Its members could have a conditional, rather than a permanent, residency status; they could be waiting to naturalize through their military service; or, they could have naturalized prior to service. Depending on their immigration status at the time their security clearance is revoked, MAVNI recruits can face various immigration concerns. Moreover, the outcome of a case can vary widely between federal circuits throughout the country, even between immigration officers in the same office or judges within a single immigration court. Caution your client against catastrophizing and encourage them to seek an immigration attorney early and often. Refer them to pro bono immigration legal services approved by the U.S. Department of Justice to avoid notario fraud.34

The best thing you can do is empower your MAVNI client to help themselves; prepare them to prove the merits of their own case.

In the meantime, advise them that proving they qualify for any immigration benefits and/or protection from removal will be their burden. If they express fear of returning to their country of origin, ask them the basis for those fears and if they have any supporting documentation. Consult U.S. Department of State country reports to corroborate their concerns.35 Certain protections may apply to those who fear persecution on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.36 Some discretionary applications turn on a balancing test of positive equities and adverse factors—such as family ties within the United States, residence of long duration in the country, evidence of hardship to the respondent and their family if removal occurs, honorable service in the U.S. armed forces, and evidence of value and service to the community.37 The best thing you can do is empower your MAVNI client to help themselves; prepare them to prove the merits of their own case.

Conclusion

Representing a MAVNI client is an uphill battle, especially if you are unfamiliar with CI processes, administrative separation procedures, and immigration law. Unlike other Service members, this security clearance revocation and mandatory separation may not be just a matter of losing their job. With the long delays and confusing processes, their patriotic journeys in pursuit of the American dream are held in unceremonious suspense. But, if you apply a critical eye to their case, pay attention to the responsible proponents, strive to understand the basics of immigration law, and care enough to steward the process, your attorney-client relationship should provide your client with much-needed reassurance and understanding. TAL

CPT Nguyen is the Resolute Support Train, Advise, Assist Command-South and Kandahar Airfield Command Judge Advocate.

Notes

1. U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-19-416, Immigration Enforcement:

Actions Needed to Better Handle, Identify, and Track Cases Involving

Veterans 1, 7 (2019)

[hereinafter GAO Report].

2. 10 U.S.C. § 504 (b)(2). 10 U.S.C. § 504(b)(2) provides a statutory basis for the Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest (MAVNI) program. The Office of the Secretary of Defense implemented the MAVNI pilot program in 2009 and it was subsequently authorized through 30 September 2017. Id.

3. By January 2018, MAVNI Soldiers represented more than 30 percent of the Army’s strategic language speakers. GAO Report, supra note 1.

4. Memorandum from the Under Sec’y of Def. to the Sec’y of Army et al., subject: Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest Pilot Program Extension (30 Sept. 2016) (including nonimmigrant categories E, F, H, I, J, K, L, M, O, P, Q, R, S, T, TC, TD, TN, U, and V) [hereinafter Military Accessions Memorandum]; Bryce H. P. Mendez et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., R45343, FY2019 National

Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues 1, 13

(2018). See also Nonimmigrant Classes of Admission, Homeland Sec. (Dec. 28, 2017), https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/nonimmigrant/NonimmigrantCOA (listing nonimmigrant categories such as temporary workers and their families as well as students and exchange visitors and their dependents); Temporary (Nonimmigrant) Workers, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-nonimmigrant-workers (Sept. 7, 2011).

5. Margaret D. Stock, Immigration Law & the Military 20-21 (2d ed. 2015); U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., Military Service During Hostilities (INA 329), in 12 Policy Manual, https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-12-part-i-chapter-3 (Mar. 10, 2021).

6. One of the security concerns was that clients had “foreign born parents”; however, that was known at the time of application, given the nature of the program.

7. Military Accessions Memorandum, supra note 4.

8. John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, Pub. L. No. 115-232, § 521, 132 Stat. 1636, 1755 (2018).

9. See Mendez et al., supra note 4; GAO Report, supra note 1. See also Memorandum from Dep’t of Army to Deputy Chief of Staff, G-1, subject: Temporary Suspension of Separation Actions Pertaining to Members of the Delayed Entry Program (DEP) and Delayed Training Program (DTP) Recruited Through the Military Accessions Vital to National Interest (MAVNI) Pilot Program (20 July 2018) [hereinafter Memorandum of Temporary Suspension].

10. See Tiwari v. Shanahan, No. 17-cv-242 (W.D. Wash. 2019) (enjoining the DoD from requiring a biennial series of National Intelligence Agency checks for continuous monitoring or security clearance eligibility purposes in the absence of individualized suspicion). See also Calixto v. U.S. Dep’t of the Army, Civil Action No. 18-1551 (D.D.C. May 16, 2019) (awaiting certification as a class action on behalf of all persons subject to final discharge or separation since 30 September 2016, whose discharge or separation has not been characterized by the Army and whose final discharge or separation decision was made without being afford due process—including adequate notice of the discharge grounds, an opportunity to respond, and due consideration of the Soldier’s response by the Army); Nio v. U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., Civil Action No. 17-0998 (D.D.C. Mar. 4, 2019) (alleging unlawful delay of Service member naturalization by imposing additional citizenship qualification and criteria not required by law); Kirwa v. U.S. Dep’t of Def., 315 F. Supp. 3d 266 (D.D.C. 2017) (filing a class action suit on behalf of those who have not received Form N-426 certifications of honorable service from the DoD).

11. See, e.g., Sean Bigley, What’s New in the World of MAVNI?, ClearanceJobs (Jan. 31, 2021) https://news.clearancejobs.com/2021/01/31/whats-new-in-the-world-of-mavni/ (noting a substantial number of MAVNI recruits receiving favorable adjudication after a period of no movement on their appeals until summer 2020); Lorelei Laird, When Things Go Wrong, Immigrants Serving in the Military Look to

Margaret Stock, ABA J. (Jan. 1, 2019, 1:05 AM), http://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/immigrants_military_margaret_stock_mavni.

12. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Reg. 135-178, Army National Guard and Reserve

Enlisted Administrative Separations (7 Nov. 2017).

13. See Military Accessions Memorandum, supra note 4, attach. 1, 2, as modified by Memorandum from the Under Sec’y of Def. to Sec’y of the Military Dep’t. et al., subject: Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest Pilot Program (13 Oct. 2017) (detailing screening requirements); Off. of the Dir. of Nat’l Intel., Security Executive Agent Directive 4, National

Security Adjudicative Guidelines (8 June 2017) [hereinafter

Directive 4] (establishing the single, common adjudicative criteria for all covered individuals who require initial or continued eligibility for access to classified information or eligibility to hold a sensitive position).

14. Directive 4, supra note 13 (providing the adjudicative guidelines as (i) Allegiance to the United States, (ii) Foreign Influence, (iii) Foreign Preference, (iv) Sexual Behavior, (v) Personal Conduct, (vi) Financial Considerations, (vii) Alcohol Consumption, (viii) Drug Involvement and Substance Misuse, (ix) Psychological Conditions, (x) Criminal Conduct, (xi) Handling Protected Information, (xii) Outside Activities, and (xiii) Use of Information Technology Systems).

15. Memorandum of Temporary Suspension,

supra note 9.

16. Tiwari v. Shanahan, No. 17-cv-242 (W.D. Wash. 2019).

17. See U.S. Dep’t of Def., Manual 5200.02, Procedures for the DoD Personnel Security Program

(PSP)

(3 Apr. 2017) (C1, 29 Oct. 2020) (designating proponent

responsibilities, investigative requirements, and determination

authorities).

18.

Off. of Mgmt. & Budget, INV 100, Freedom of Information/Privacy

Act Records Request for Background Investigations

(Mar. 2020). You should submit a copy of two forms of government-issued

identification and the form OMB No. 3206-0259 to the Defense

Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA).

Id.

See also Exec. Order No. 13,869, 84 Fed. Reg. 18125, § 925 (Apr. 24, 2019). Note that, effective 27 September 2019, DCSA’s predecessor—the National Background Investigation Bureau—officially transferred from the Office of Personnel Management to the Department of Defense. Id.

19. 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(A), (B) (prescribing twenty working days to respond and a ten-day extension for unusual circumstances such as voluminous records or need for consultation with another agency). For more information on FOIA, see 32 C.F.R. pt. 286, DoD Freedom of Information Act Program (2020); U.S. Dep’t of Def., Dir. 5400.07, DoD Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Program

(5 Apr. 2019); U.S. Dep’t of Def., Manual 5400.07, DoD Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Program

(25 Jan. 2017);

U.S. Dep’t of Army, Reg. 25-55, The Department of the Army Freedom of

Information Act Program (19 Oct. 2020).

20. Directive 4, supra note 13.

21. Id. at 9.

22. Id.

23. Id. at 10.

24. See, e.g., JAGConnect-Legal Assistance, milBook, https://www.milsuite.mil/book/groups/army-legal-assistance (last visited Mar. 29, 2021) (note that access to the website’s content requires membership in the group).

25. See, e.g., 1064 Policies, Immigr. Pol’y Tracking Project, https://immpolicytracking.org/policies/ (last visited Mar. 15, 2021) (tracking changes from 2017 through 2021);

MAVNI Fed. Class Action Litig., https://dcfederalcourtmavniclasslitigation.org/ (last visited Mar. 15, 2021).

26. U.S. Dep’t of Def., Adjudicative Desk Reference

(Mar. 2014).

27.

Def. Off. of Hearings & Appeals, https://search.usa.gov/search?affiliate=doha (type in relevant

adjudicative guideline into the search bar; then select relevant result)

(last visited Jan. 25, 2020).

28. Digital signatures and/or notarized handwritten signatures can

contribute to the credibility of their authors.

29. The MAVNI Operations Team is nested in Headquarters, Department of

the Army (HQDA) DCS, G-1 (DAPE-MPA). The email address for the MAVNI

Operations Team’s general inquiries is

usarmy.pentagon.hqda-dcs-g-1.mbx.dmpm-mavni-ops@mail.mil. See the

appendix for more addresses and contact information of agencies involved

in the security clearance revocation and separation process, current as

of 19 March 2021.

30.

U.S. Dep’t of Army, Reg. 635-200, Active Duty Enlisted Administrative

Separations

(19 Dec. 2016).

31. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Reg. 601-210, Regular Army and Reserve Components

Enlistment Program

(31 Aug. 2016).

32. See 8 U.S.C. § 1451(a).

33. 8 U.S.C. § 1440(c).

34. Notario fraud is a form of fraud involving individuals holding themselves out to be qualified to offer legal advice or services without possessing such qualifications. See About Notario Fraud, Am. Bar Ass’n (Nov. 11, 2020), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_interest/immigration/projects_initiatives/fightnotariofraud/about_notario_fraud/.

35. See Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, U.S. Dep’t of State, https://www.state.gov/reports-bureau-of-democracy-human-rights-and-labor/country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/

(last visited Mar. 29, 2020).

See also Country Conditions Research, U.S. Dep’t of Just., https://www.justice.gov/eoir/country-conditions-research (Oct. 9, 2020)

(click on the letter for the country that you wish to view; select the

country that you wish to view; and click on the relevant file).

36. 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42)(A).

37. Id. §§ 1229a(c)(4)(A)(ii), 1229b.

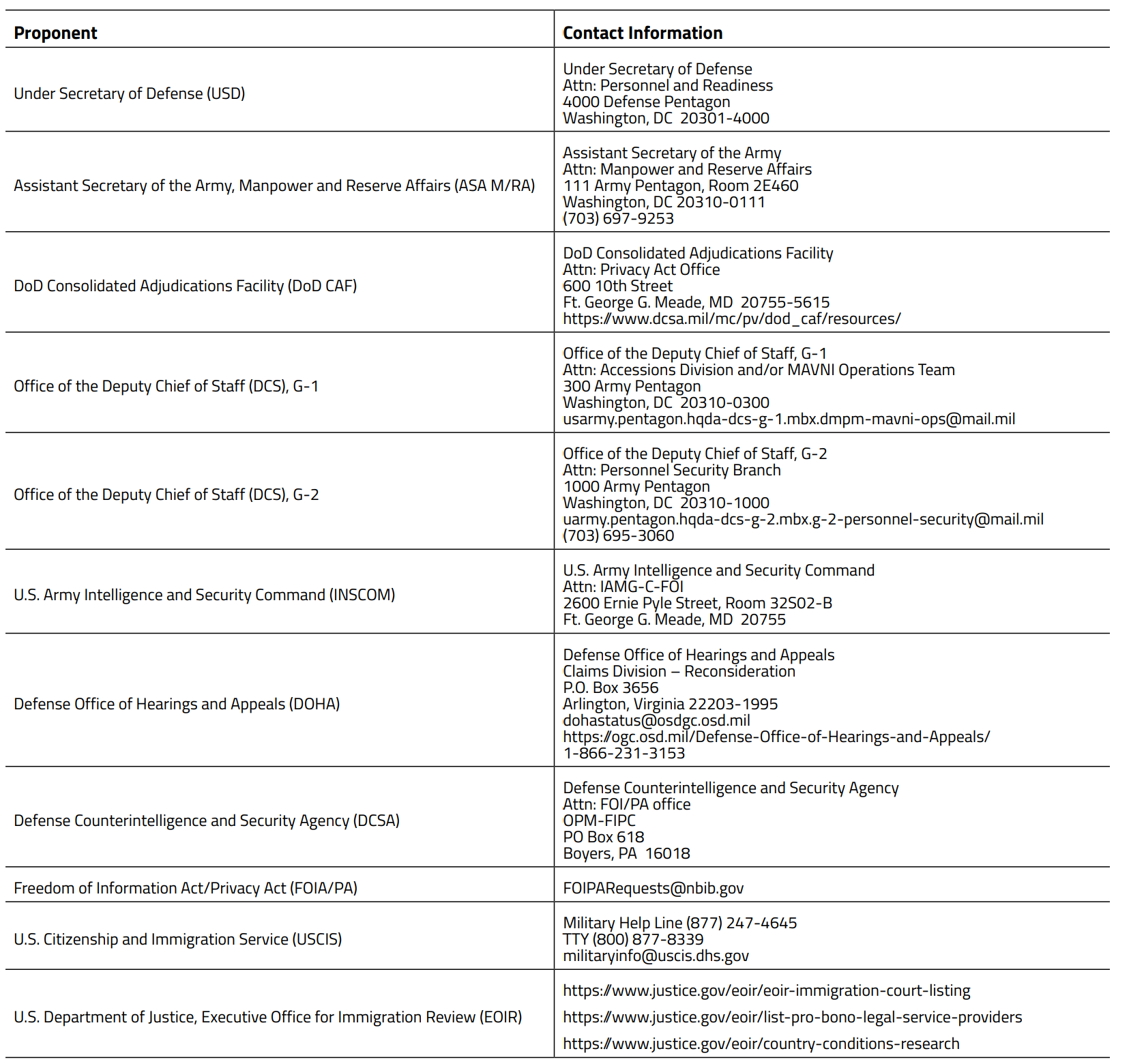

Appendix: Agency Contact Information

The most difficult part of defending a MAVNI client is the lack of agency transparency. Therefore, here are the proponents and contact information available at the time of publication discussed throughout this article: