The Decker Auditorium entrance to The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School in Charlottesville, Virginia. (Credit: Jason Wilkerson/ TJAGLCS)

Court Is Assembled

Can Principled Counsel Be Taught?

By Colonel Sean T. McGarry

There is a new leader in your organization. First impressions are

good.

The leader projects confidence, charisma, and competence. Initially, the

rapport developed across the organization is strong. However, as time

goes on, what was initially projected as confidence increasingly gives

way to an aggressiveness approaching bullying. The leader vents his

frustrations in public, often in a pointed way at particular

individuals. As first-impression good behavior wears off in favor of

familiarity and comfort, poor language and boorish humor becomes more

frequent. The leader’s Type-A performance and the results they produce

remain top-notch, but organizational morale is significantly slipping.

Nobody wants to complain for fear of becoming the next target or

becoming embroiled in an investigation that may not end well for anyone.

What do you do?

Leadership and Principled Counsel

Every organization needs to know who they are and what they are about.

Mission and vision statements are not unique to the military and are

ubiquitous across organizations of all types because they provide

superordinate goals that bring people together and guide unified effort

in the same direction. The Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) Corps is no

exception. In order to facilitate and sustain our diverse and high

performing organization, we need to clearly and repeatedly identify, not

just what we do, but how we do it—that is who we are and how we bring

our individual teammates together to continue providing the gold

standard of legal support across a world-wide practice that is “the most

consequential practice of law on earth.”1

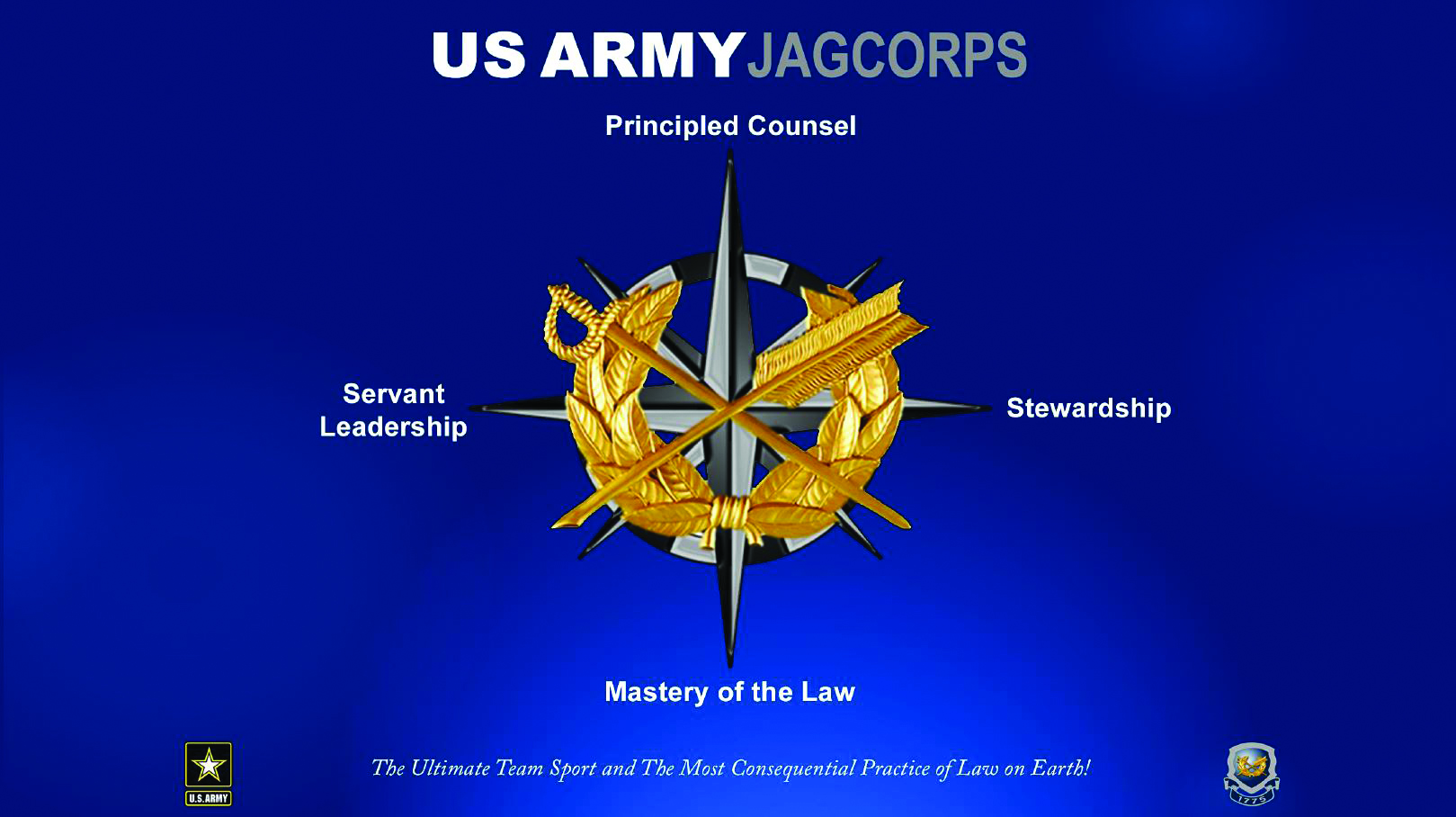

The JAG Corps’s identity and core values are firmly rooted in the “North

Star of our Regiment—Substantive Mastery, Stewardship, Servant

Leadership, and the spirit behind each of them—Principled Counsel.”2

Those Four Constants start with our JAG Corps senior leaders and

permeate throughout the Regiment as we collectively develop and grow

formal and informal leaders across our formation. The ultimate goal, of

course, is to have those North Star elements—our Four Constants—be

naturally occurring and instinctive guides for what we collectively do

every day across the globe.

Our senior leaders cannot be like the individual described above;

instead, they must emphasize and cultivate the Four Constants—especially

that of Principled Counsel—to retain and attract the kind of people we

want in our Corps. Senior leaders must serve as the reference point for

what right looks like—it is through their words and deeds that office

and Corps climates will develop and maintain social mores and norms

consistent with our organization’s identity. In a situation where local

leadership behavior is not consistent with senior leader messaging,

those local leaders will likely be viewed as paying trite lip service to

our Corps’s core values, and in turn, to its identity. That effect can

increase our teammates’ dissatisfaction with “bait and switch”

bitterness, which will result in low morale, poor performance, and,

ultimately, loss of talent from our ranks. Exit surveys continue to

discuss the importance of the Corps’s leadership in talent retention,

and also how it relates to both personal and professional

satisfaction.3The Fort Hood Independent Review Committee’s report is a recent example of the damage that can be done within an organization when local culture is seen as inconsistent with institutional values and messaging.4 The report also further highlights the importance of equipping our leaders to avoid those pitfalls.

Teaching Principled Counsel

So, how do we best prepare our JAG Corps leaders to exemplify our core values for our junior members? The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School (TJAGLCS) inculcates Principled Counsel through early and repeated exposure to our JAG Corps’s Four Constants—reinforced with Army doctrine5 and modeled behavior at the organizational and individual level. The process begins with early exposure for our initial entry populations with basic concepts like the Army Values, officership, and the basic premise for Principled Counsel. Acculturation to the important tenets of our Corps is continued at the institutional level throughout JAG Corps-specific Professional Military Education.

During the Graduate Course (GC), students are exposed to a robust leadership curriculum rooted in Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession; they then continue the transition from student to formal leader through a GC/Officer Basic Course (OBC) crossover program that matches GC and OBC students in a mentor-type relationship. The intent of the crossover is to expose OBC students to basic leadership concepts while further internalizing those same concepts in the GC counterparts as they prepare to assume formal leadership positions when they return to the field. Small GC peer-seminar groups are also key for both substantive material as well as network-building discussion. The seminar highlights more common challenges our newest field-grade officers will face in the field and provides a platform to discuss approaches to those challenges in light of doctrine, leadership lessons, and the experiences brought to the table by seminar participants.

Does this approach work? Anecdotally, yes, it does. The shared reflection of recent GC graduates as well as feedback from JAG Corps leaders who did not have the benefit of a formal leadership professional development program during their GC experience is illustrative.6 Recent graduates found ADP 6-22 concepts, along with seminar discussions of those concepts, to be powerful tools in recognizing inconsistent behaviors early and formulating an approach to combat them. Similarly, the more seasoned JAG Corps leaders regularly shared how their own developmental experiences would have benefitted from a similar institutional program, especially since they have been responsible for developing Principled Counsel within our junior leaders. It is one thing to intellectually know these concepts, but it is another to utilize them in daily practice. As one recent GC student shared,

you must now do your part to “clean up” this [negative] behavior by setting a positive example as an informal leader. To this end, you must immediately commit to engaging in civil discourse, rather than disrespect. You must operate with integrity by owning your part in the state of the office.7

Recent GC students are more empowered to be effective leaders through their shared experiences and robust discussions during their time at TJAGLCS. Leadership challenges, like legal issues, are generally not completely novel. Whether a particular challenge arises within a brigade, office of the staff judge advocate, or somewhere else, the worldwide JAG Corps network is available to support. Nobody in our Corps is ever alone—when our team is enabled with formal instruction that highlights and reinforces our institutional values, our leaders are best equipped and empowered to ensure Principled Counsel continues to be our enduring hallmark. TAL

COL McGarry is the Dean of The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Notes

1. The Judge Advoc. Gen. & Deputy Judge Advoc. Gen., U.S. Army, TJAG & DJAG Sends, Vol. 41-01, Message to the Regiment (13 July 2021).

2. The Judge Advoc. Gen. & Deputy Judge Advoc. Gen., U.S. Army, TJAG & DJAG Sends, Vol. 40-16, Principled Counsel—Our Mandate as Dual Professionals (9 Jan. 2020).

3. This assertion is based on the author’s recent professional experiences as the Dean, The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, Charlottesville, Virginia, from 15 July 2020 to present, and as the Staff Judge Advocate, 1st Armored Division and Fort Bliss, Texas, from 25 June 2017 to 20 July 2019.

4. Christopher Swecker et al., Fort Hood Indep. Rev. Comm., Fort Hood

Independent Review Committee Report

(2020). In describing the lack of Fort Hood, Texas, Sexual

Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention Program effectiveness, the

Fort Hood Independent Review Committee found that

“[t]he main cause, however, was the failure of leadership to get the message to the ranks where the lion’s share of the violations occurred. Operational imperatives overshadowed the safety and security of the Soldiers who were vulnerable and essentially on their own.” Id. at 43.

5. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession (31 July 2019) (C1, 25 Nov. 2019).

6. This assertion is based on a subjective assessment of individual professional experiences.

7. Leadership Seminar Vignette, 69th Graduate Course, The Judge Advoc. Gen.’s Legal Ctr. & Sch. (2021).