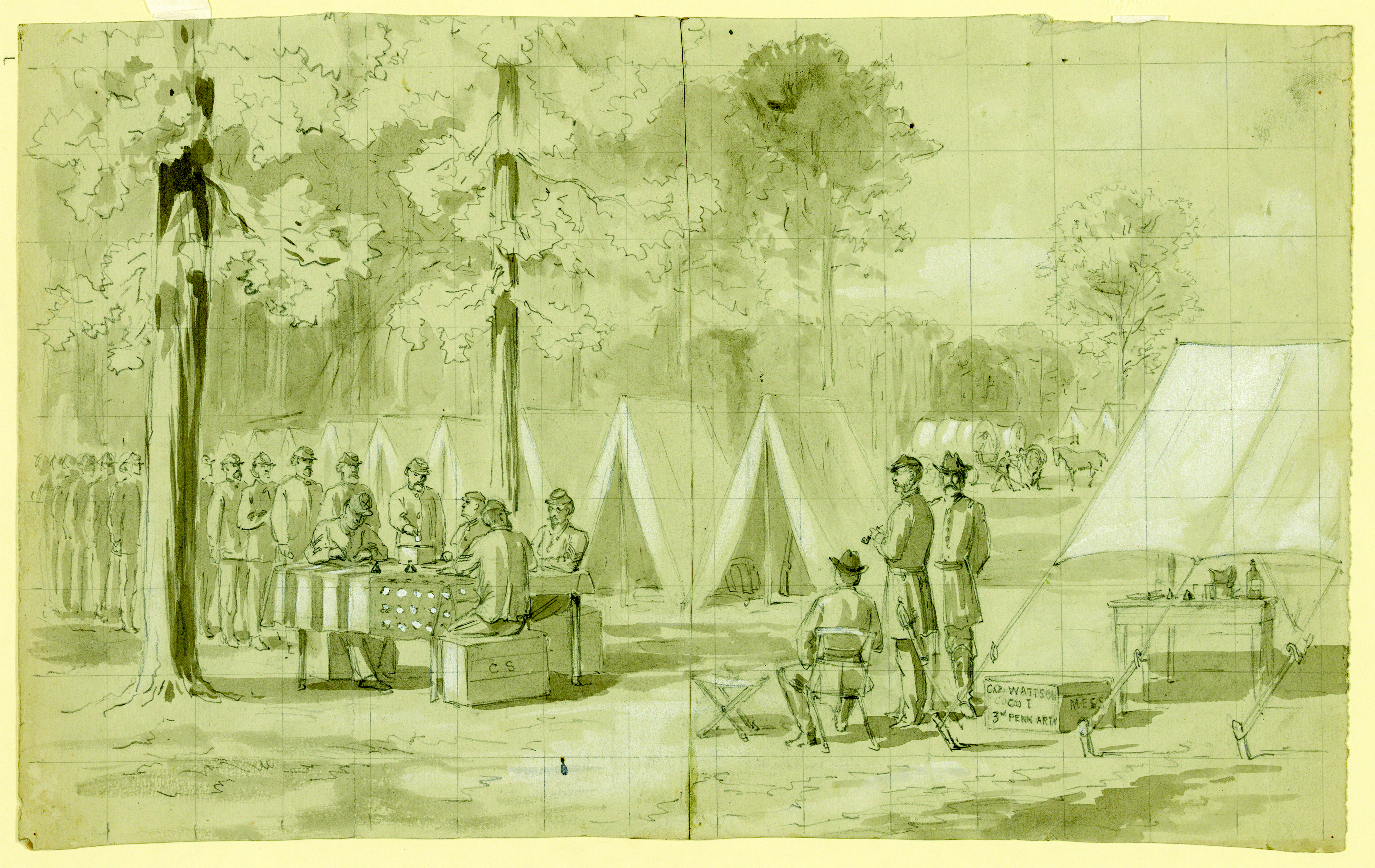

A sketch of members of the Army of the James voting during the Civil War in 1864 (Credit: Waud William/Library of Congress).

Closing Argument

Officers Should Vote Early and Often

By Lieutenant Colonel Jess R. Rankin

The American military jealously guards its status as an apolitical institution.This status is enshrined in regulation and tradition dating back to George Washington.1 Some well-intentioned officers take this tradition and Professor Huntington’s model of a modern apolitical Soldier to a logical and self-defeating extreme when they advocate that officers abstain from voting.2 Persuading officers to abstain from voting to maintain professional impartiality is a cure far more insidious than the proposed disease of political partisanship. It misinterprets our oath of office, ignores American history and constitutional framework, and falsely proposes a bright line separating politics from war. American Soldiers’ connection to their country through the exercise of the secret ballot is not a weakness, but a strength. Voting makes officers more effective and, more importantly, better citizens.

The founding fathers had a fear of standing armies. This fear was inherited from colonial memories of the English Civil War3 and then reinforced during the age of Napoleon.4 A fear of standing armies is reflected in our founding documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Federalist Papers, and the Constitution. However, it is not fear of such a standing army itself, but rather a fear of who controls that standing army. The Declaration of Independence lists all the abuses of the British King. Prominent among those abuses is the maintenance of a standing army in the colonies responsive solely to the King.5 The founders’ fears and experiences with the British monarchial army are reflected in the U.S. Constitution with the most glaring example being the reservation to Congress the ability to fund and raise an Army.6 Additionally, our Bill of Rights explicitly prevents the forced quartering of Soldiers in private homes with the 3rd Amendment.7

The founders feared a standing army that would be used to trample democracy and advocated maintaining a small army with primary reliance on the militia.8 In our modern age, with a large military establishment, suggesting officers should not vote removes one of our most effective democratic safeguards. Officers abdicating their right to vote so they may more loyally fulfill the orders of a president reduces them to mercenary agents of the executive branch. Concern about impartiality to the presidency also blindly ignores the constitutional obligations officers owe beyond a resident under the Constitution. Our oath as officers is to support and defend the Constitution from enemies foreign and domestic.9 In order to support and defend the Constitution, we must serve both Congress and the President.

Arguing officers should abstain from voting also ignores American military history. During our greatest wartime struggles, both in the Civil War and World War II (WWII), Soldiers regularly voted in wartime. While General Grant did not vote in the 1864 election, he regularly encouraged subordinates to support Soldiers’ ability to vote. This verbal encouragement was reinforced in deed with furloughs home and mailed ballots.10 Efforts were also conducted in WWII to ensure GIs could vote in far flung theaters during the decisive year of 1944.11 The Soldiers ballot, including officers, was considered crucial to President Lincoln’s reelection in 1864.12 If officers had abstained from voting in 1864, and thereby allowed General McClellan to be elected on a peace ticket, they would have invalidated the very military purpose for which they had spent the last four years fighting. This highlights the logical absurdity in trying to divorce the political realm from the military application of force.

Perhaps most damning is how overbroad the results would be to abstain from voting to preserve political impartiality under a president. Presidential elections happen every four years, congressional elections every two years, and local elections and initiatives every year. Should someone who is concerned about remaining impartial about the presidential election outcome truly skip the ballot box, thereby forgoing a vote on the local school bond initiative, state environmental proposition, and representative to Congress? This fear of a slippery slope of political contagion seeping into professional advice would cut the very cords that tie us to the society we protect. Officers voting on issues affecting their families and communities constitutes a vital personal tie to the body politic. To remove that intimate connection would be creating conditions for resentment, apathy, and, worst of all, disregard.

Exercising suffrage rights makes officers more effective professionally, not less so. There is a recurring desire to have clean lines separating politics from the use of force. The desire to abstain from voting in order to keep military advice pure reflects this philosophy. It is a false panacea, for it ignores reality as espoused by Clausewitz’s dictum that war is conducted for the purposes of political objectives.13 Politics and warfare cannot be neatly separated, and we forget this at our peril. Officers must understand the political forces involved in the decisions they are ordered to execute, otherwise they are operating blindly. Officers will be most effective if they are invested in the successful outcome of these political decisions by participating in the democratic process. Otherwise we are merely professional employees of the Executive.14 Being an active participant in our political process through the practice of informed voting provides insight and gives us “skin in the game.”15 Armies invested in their society fight more effectively and endure far greater privations than purely professional forces. This can be seen throughout western military history from the Greek Persian wars, through both American and French Revolutionary Wars, and perhaps to the modern wars of counterinsurgency.

Our highest oath as officers is to the Constitution, and we will defend the Constitution far more deeply and effectively if we actually exercise our rights as guaranteed under the Constitution. We will be more successful officers if we understand, and are committed to, the politics driving military decisions, and most importantly, we will be better citizens. TAL

LTC Rankin is an Associate Professor in the Contract and Fiscal Law Department at The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Notes

1. U.S. Dep’t of Def., 5500.07-R, Joint Ethics Regulation ch. 6 (JER) (2018); Ron Chernow, Washington: A life 434–36 (2010).

2. M.I. Cavanaugh, I Fight for Your Right to Vote. But I Won’t Do It Myself, N.Y. Times (Oct. 19, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/19/opinion/i-fight-for-your-right-to-vote-but-i-wont-do-it-myself.html; Samuel Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations (1957).

3. Kevin Phillips, The Cousins’ War 107 (1999).

4. Elizabeth Webber & Mike Feinsilber, Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Allusions 345 (1999). Man on horseback is a military leader who presents himself as the savior of the country during a period of crisis who assumes dictatorial powers. Early in Napoleon’s consulate he tried to draw comparisons to George Washington as a military leader called to political leadership. The irony being, Napoleon later failed to follow President Washington’s example in stepping down from power, instead crowning himself as Emperor. Andrew Roberts, Napoleon 233, 353 (2014).

5. After the preamble in the Declaration of Independence, there is a list of injuries and usurpations by the British King on the American Colonists. These include maintaining a standing army in time of peace without legislature approval, quartering soldiers in private homes, and the utilization of mercenary troops.

6. U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 12; U.S. Const. amend. II.

7. U.S. Const. amend. III.

8. The Federalist No. 8 (Alexander Hamilton). This reliance on the militia as a democratic safeguard was then subsequently enshrined in the 2nd Amendment. U.S. Const. amend. II.

9. 10 U.S.C. § 1031 (2018).

10. James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom 804 (1988).

11. Don S. Inbody, Monkey Cage, Wash. Post (Nov. 11, 2015).

12. McPherson, supra note 10, at 805.

13. Carl Von Clausewitz, On War 87 (Michael Howard & Peter Paret eds., Princeton University Press 1976).

14. Lord Alfred Tennyson, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1854). A famous charge during the Crimean War with no hope of success, but executed regardless and with great loss of life.

15. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Skin in the Game (2018). Chernow, supra note 1, at 434–36.