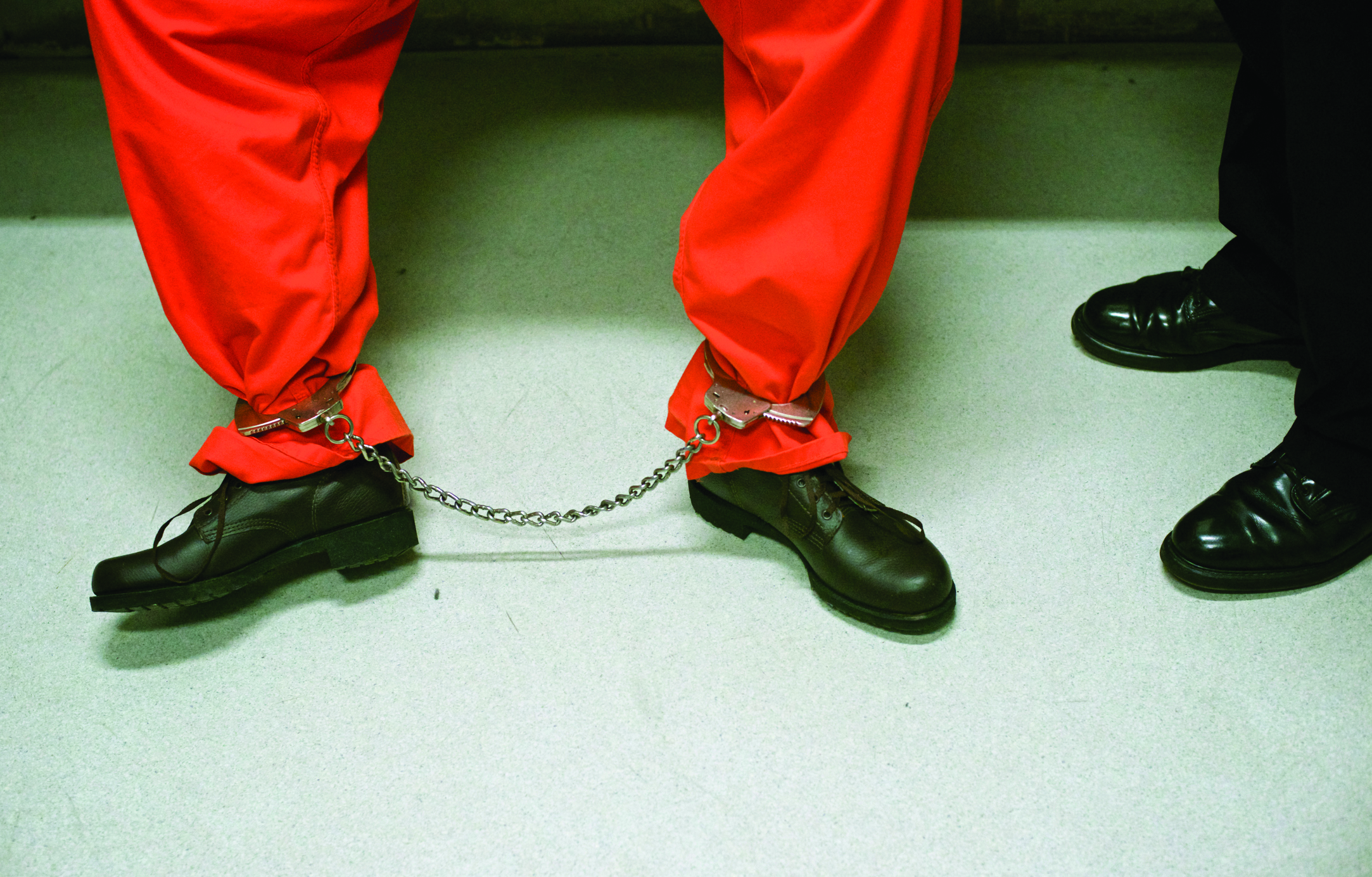

(Credit: istockphoto.com/Bastiaan Slabbers)

A Writ of Habeas Corpus

Ad Prosequendum

Federal Authority to Secure Soldiers Who Are State Prisoners at Court-Martial

Captain Patrick S. Wood

Imagine that an active duty Soldier begins to sexually abuse his minor daughter while stationed at Fort Sam Houston, Texas.Unfortunately, his criminal behavior continues after his Permanent Change of Station (PCS) to Germany because his daughter is too fearful to report her father’s sexual abuse to authorities. Indeed, the abuse continues even after the family’s next PCS to Virginia. The Soldier is later assigned to Fort Riley, Kansas, but occasionally visits his family who remains in Virginia, where he continues to sexually abuse his daughter. Thankfully, while the Soldier is assigned to Fort Riley, the victim finally develops the courage to report her father’s sexual abuse that occurred in Texas, Germany, and Virginia to Virginia authorities. Ultimately, the accused Soldier confesses to Virginia authorities that he sexually abused his daughter in Virginia.

Crimes have occurred in Texas, Germany, and Virginia while the Soldier was on active duty. Can the Army assert jurisdiction in each instance? How should a trial counsel proceed after learning of these allegations? Presumably, the easiest way forward would be for each of the civilian jurisdictions to defer prosecution to the military because the military has jurisdiction over all of the offenses.1 However, Virginia is adamant about prosecuting the offenses that the Soldier committed in Virginia. The commonwealth has a confession and feels strongly about prosecuting this Soldier for the heinous crimes that occurred within its borders. Further, Virginia intends to expeditiously prosecute its case in light of the strength of its evidence. The accused eventually pleads guilty in Virginia for the crimes committed there, and a circuit court sentences the accused to twelve years in prison.

Assuming that charges have been preferred covering the crimes that occurred in Texas, Germany, and Virginia, what should Fort Riley do now? Let the crimes that occurred in Texas and Germany go unpunished and simply eliminate the Soldier based on the conviction in Virginia?2 Transfer the case to an Army installation in Virginia in order to facilitate easier transportation of the Accused to and from proceedings? Proceed with a court-martial at Fort Riley? Ultimately, with the goal of ensuring that the Accused is adequately punished for the entirety of his criminal conduct, Fort Riley decides to pursue the charges against the Accused covering his criminal behavior that occurred in Texas and Germany. Now, Fort Riley is faced with logistical and procedural obstacles. The accused is sitting in a Virginia prison. How will the Army coordinate his release from state authorities in order to stand trial at Fort Riley, Kansas?

This article discusses the authority for, and benefits of, using a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum3 in order to secure the presence of a Soldier, who is confined in a state prison, at a court-martial; highlights why a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum should be preferred over a detainer under the Interstate Agreement on Detainers Act4; and attempts to provide a practical framework that can be used if a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum is pursued.

The All Writs Act and the Military Judge

The All Writs Act5 allows the “Supreme Court and all courts established by an Act of Congress [to] issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.”6 Importantly, military courts are included as courts established by an Act of Congress empowered to issue writs.7 “[M]ilitary courts, like Article III tribunals, are empowered to issue extraordinary writs under the All Writs Act.”8

Debate exists as to what all “military courts” this grant of authority extends. Case law and the Rules for Courts-Martial are clear that military appellate courts are courts created by Congress for purposes of the All Writs Act and as such can resort to and entertain petitions for extraordinary relief.9 Unfortunately, few courts have answered whether or not the military judge presiding over a court-martial has powers under the All Writs Act.

Albeit in dissent, Senior Judge Gray of the Air Force Court of Military Review—while discussing how a general court-martial in session is a court of the United States provided for by an Act of Congress where the military judge performs in the image of a civilian judge—made an eloquent argument in favor of the military judge exercising such power when he stated: “It necessarily follows, then, that the military judge in the present case possesses all of the inherent powers necessary or appropriate in aid of the jurisdiction of the court-martial, including those expressly conferred upon Federal courts by the All Writs Act. It is inconceivable to me that Congress in ‘revolutionizing military justice’ and establishing a completely independent trial judiciary whose judges are to perform in the image of a Federal district judge during the trial, intended him not to exercise power to grant relief on an extraordinary basis, when the circumstances so require.”10 In the same case, Senior Judge Gray, while discussing how no civilian jurisdiction had permitted extension of All Writs powers to courts of limited jurisdiction, stated the following: “In this connection I repeat that a general court-martial is a court of unlimited jurisdiction albeit only with respect to military criminal cases. The fact that a court is empowered by Congress to act only in a specially defined area of law does not make it any the less a court established by Congress.”11 Additionally, when presented with an opportunity to state whether or not a military judge presiding over a court-martial has power under the All Writs Act, the United States Court of Military Appeals has avoided answering the question.12

Considering the reasoning laid out above and judicial reluctance to answer the question, the argument can be made that once a military judge is detailed to a general court-martial that has been properly convened pursuant to a congressional statute, then that court is “established” for purposes of the All Writs Act.13 The counter argument is that Congress does not establish specific courts-martial and did not intend for military judges, given that they do not sit on courts of continuous jurisdiction and only deal with a specific court-martial, to have authority under the All Writs Act.

Congress does not pick who sits on the military appellate courts and it has no say as to who sits on the bench at Fort Sill; yet the former clearly have authority under the All Writs Act.14 Concerns about military judges at the court-martial level abusing authority under the All Writs Act can be allayed by the fact that the military appellate courts and the Supreme Court provide additional layers to correct the military judge that has lost their way.15 More importantly, the writ is an exceptional remedy and the professional judges in our military understand that only extraordinary circumstances will warrant its issuance. Further, case law supports the notion that, unless Congress has said otherwise, federal judges should have the authority to craft and issue writs in the pursuit of justice.16 “Unless appropriately confined by Congress, a federal court may avail itself of all auxiliary writs as aids in the performance of its duties, when the use of such historic aids is calculated in its sound judgment to achieve the ends of justice entrusted to it.”17 If no common law form of habeas corpus fits a situation where it is necessary to bring a prisoner to court, the court may issue its own generic variety of habeas corpus to insure the prisoner’s presence.18 If desired, Congress or the Supreme Court should state that military judges at the general court-martial level do not have power under the All Writs Act. Until such time, military judges at this level should issue extraordinary writs when appropriate.

Finally, an argument can be made that the writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum, our focus here, more closely resembles regular criminal processes and really was not intended to be an extraordinary writ. “Moreover, when federal courts have had occasion to resort to habeas corpus in aid of jurisdiction, the writ has been used primarily as a procedural device to obtain a prisoner’s presence in court where such presence was vital to determination of a pending cause. This use of habeas corpus as an auxiliary writ seems in no way to involve a grant of extraordinary relief, but instead resembles the ordinary judicial process to secure the presence of parties and witnesses.”19

The Writ of Habeas Corpus Ad Prosequendum

“[E]xpressly included within this authority [to grant writs of habeas corpus] is the power to issue such a writ when it is necessary to bring a prisoner into court to testify or for trial.”20 Further, “the statutory authority of federal courts to issue writs of habeas corpus ad prosequendum to secure the presence, for purposes of trial, of defendants in federal criminal cases, including defendants then in state custody, has never been doubted.”21 As for timing, writs of habeas corpus ad prosequendum are issued by a court when charges have been lodged against the prisoner.22

The purpose of the writ is to request that the individual who has custody of the accused make him available to stand trial in another sovereign.23 Moreover, a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum “is a court order requesting the prisoner’s appearance to answer charges in the summoning jurisdiction.”24 More importantly, “a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum . . . is not a ‘detainer’ within the meaning of the Agreement on Detainers.”25 Unlike a detainer, which merely puts prison officials on notice that the individual is wanted in another jurisdiction, the writ is immediately executed.26 In fact, a prisoner is not even in custody when he appears in another jurisdiction’s court pursuant to an ad prosequendum writ.27 Rather, the prisoner is merely loaned to that jurisdiction.28 Thus, the sending sovereign’s custody and control over the incarcerated accused is never interrupted.29 As such, the prisoner remains within the legal custody of the sending state. “The writ swiftly runs its course, and is no longer operative after the date upon which the prisoner is summoned to appear.”30 Principles of comity require that when the federal ad prosequendum writ is satisfied, the receiving federal jurisdiction returns the incarcerated accused to the sending sovereign.31

Accordingly, as outlined above, once charges have been referred to a properly convened general court-martial, All Writs Act jurisdiction attaches, and the military judge detailed to the case has the power to issue a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum in order to secure a state prisoner for that court-martial.32 The military judge can issue such a writ to the state official who has custody of the accused directing the state prisoner’s appearance at a court-martial. Because the writ is to be immediately executed and the state prisoner will merely be on loan to the U.S. Army, the state never loses legal custody of the state prisoner. Once the Accused has been tried at a court-martial, the federal government must return the prisoner to state officials as soon as possible. Rule for Courts-Martial 1107(d)(3) supports this process in that it allows the convening authority to defer service of the sentence until the Accused has been permanently released to the armed forces by a state.33

Most importantly, once the state receives a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum from a military judge, it must comply with the order.34 In United States v. Pleau, the court stated:

That a state has never had authority to dishonor an ad prosequendum writ issued by a federal court is patent. Under the [Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution], 28 U.S.C. § 2241(c)(5)—like any other valid federal measure—overrides any contrary position or preference of the state, a principle regularly and famously reaffirmed in civil rights cases . . . . State interposition to defeat federal authority vanished with the Civil War.35

In Pleau, the federal government wanted to prosecute a state prisoner on charges that carried the possibility of the death penalty.36 The governor opposed the death penalty, so he cited the Interstate Agreement on Detainers Act and principles of comity as giving him the authority to deny the federal request.37 The First Circuit cited United States v. Mauro38 and stated that the federal government always has the authority to obtain a state prisoner by filing a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum and that the Supremacy Clause required that the states comply with issued writs because they have never had the authority to dishonor such a writ.39

Detainer Under the Interstate Agreement on Detainers

The Interstate Agreement on Detainers Act has been enacted by over forty-five states to encourage the expeditious and orderly disposition of charges outstanding against a prisoner.40 “It prescribes procedures by which a member [s]tate may obtain for trial a prisoner incarcerated in another member jurisdiction and by which the prisoner may demand the speedy disposition of certain charges pending against him in another jurisdiction.”41 However, the Act is not triggered until a detainer is filed with the custodial state by another state having untried charges pending against the prisoner.42 Once filed, the detainer only puts the prison on notice that another jurisdiction wants to try the prisoner upon their release from prison. The receiving state must also submit a written request for temporary custody or availability of the prisoner.43

If the federal government files a detainer against a state prisoner, then the terms of the Interstate Agreement on Detainers will be controlling.44 Once filed, “[t]he warden of the institution in which the prisoner is incarcerated is required to inform him promptly of the source and contents of any detainer lodged against him and of his right to request final disposition of the charges.”45 If a prisoner does request final disposition of his charges, then the prisoner must be brought to trial by the requesting jurisdiction within 180 days.46 Once the prosecuting authority has obtained the presence of the prisoner, “trial shall be commenced within [120] days of the arrival of the prisoner in the receiving State.”47 Additionally, the governor of the sending state may disapprove the request, upon his own motion or upon motion of the prisoner, within thirty days after the request is received.48 Further, the request cannot be honored until these thirty days pass.49 In the event that the request is honored, the prisoner must be tried by the receiving state before being returned to the state where he was imprisoned.50 If this does not happen, the charges are of no further force and effect and will be dismissed with prejudice.51

Why the Writ of Habeas Corpus Ad Prosequendum is Preferable to a Detainer

When a military judge issues a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum to the state official with custody of the accused, it is an immediately executable federal court order that the state must comply with. The state must loan the prisoner to the federal government, but the state never loses legal custody of the prisoner. The federal government’s only obligation is to return the prisoner to the state after trying them at a court-martial. Finally, because it is not a detainer, the federal government is not bound by the requirements of the Interstate Agreement on Detainers Act which imposes multiple restrictions and penalties for non-compliance.52

When the federal government lodges a detainer to procure a state prisoner at a court-martial, the federal government is merely providing the state with notice that it wants to try the Accused at a later date.53 This must be followed up with a written request for temporary custody.54 Further, even if both the detainer and a written request are filed, the governor of the sending state can disapprove the request.55 As a result, a properly filed detainer is not immediately effective and offers no guarantee that the state will comply with the request. Additionally, once the detainer is filed, the federal government is bound by the Interstate Agreement on Detainers Act.56 The result is that the state prisoner can request speedy disposition of the charges against them.57 If such a request is made, the federal government must bring the prisoner to trial within 180 days or within 120 days of receiving the prisoner at their installation.58 This can create real problems if a detainer is filed before any real efforts have been made to prosecute the accused. Finally, since the federal government has legal custody of the accused, all outstanding charges against the accused must be disposed of before the accused is returned to the sending state.59 If they are not, all charges will be dismissed with prejudice.60 As a result, filing a detainer does not guarantee that the state will produce the accused for a court-martial, and it imposes requirements that, if violated, can lead to dismissal of the federal charges against the accused. This can all be avoided by the issuance of a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum.

Practical Application

After preferral, but before referral of charges, the trial counsel should coordinate with their installation Provost Marshall Office and the U.S. Marshall Service in order to ensure that seamless transport and custody of the accused can be accomplished from the sending state to the federal government, and vice versa.61 The trial counsel should also coordinate with state officials to see if any additional requirements are likely to be required and to see whether resistance to a writ is likely. Doing these things will allow the military judge acting on the matter to make an informed decision.

Next, the charges should be referred to a general court-martial and served on the accused. Referral to a properly convened general court-martial is critical because there must be primary jurisdiction to which the All Writs Act can attach.62 As stated before, a court-martial does not have continuous jurisdiction and, pursuant to statute, needs the following in order to be properly convened and to establish primary jurisdiction: a convening order issued by the proper convening authority that establishes the court-martial and the referral of charges to that court-martial by competent authority.63 Once properly convened, however, a given court-martial may try an unlimited number of cases so long as they are properly referred to it and will exist indefinitely because customary practice does not include terminating a given court-martial; rather, no new cases are referred to it.64

Following referral, the government should file a motion for appropriate relief with the military judge outlining their authority to issue extraordinary writs and asking that they issue a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum.65

Generally, the military judge will have to determine if issuance would be in aid of existing jurisdiction.66 Assuming there are no jurisdictional issues, this is likely the easier hurdle as the accused’s presence is necessary to decide the case at hand. It is important to make clear to the military judge that issuance would not expand power, but rather only aid in the exercise of authority that the military judge already has.67 The military judge will also have to determine whether or not issuance of the writ would be agreeable to the usages and principles of law.68 In other words, the military judge will have to decide if the case before them is an exceptional case where extraordinary relief is reasonably necessary in the interest of justice.69 A military judge will likely have to decide, amongst other things and with no one factor being dispositive or always relevant, if other adequate means exist to obtain the relief requested.70 Arguing that production of the accused via the writ is agreeable to the usages and principles of law should focus on the writ’s purpose. “The historic and great usage of the writ, regardless of its particular form, is to produce the body of a person before a court for whatever purpose might be essential to the proper disposition of a cause.”71 Further, if proper, arguments should be advanced that, without its issuance, the government does not have other adequate means or any guarantees that ensure the accused will be produced for court-martial.

If granted, the writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum should be signed by a military judge and sent to the prison warden or official that has custody of the accused. A copy of the writ should also be sent to the state department of corrections, the state attorney general, and the installation Provost Marshal Office. At a minimum, the writ should outline the authority for the writ, the accused who will be transported, the location they will be transported to, when this transport will take place, why they are being transported, which federal agents will transport the accused, when and where the accused will be returned by federal agents, and where the accused will be held while awaiting the court-martial.

For example, in Jiron-Garcia v. Commonwealth of Virginia,72 the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia issued a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum directly to the supervisor of the Riverside Regional Jail directing him to surrender Jiron-Garcia to the U.S. Marshal on 20 October 2004 for a 1430 court proceeding.73 “The writ further provided that appellant was to be ‘returned forthwith by the U.S. Marshal’ to Riverside Regional Jail.”74

Proper coordination between the trial counsel, the installation Provost Marshal Office, the U.S. Marshal Service, and the state government officials involved in prosecuting and/or incarcerating the accused should occur to ensure that all logistical requirements are addressed and a clear path that avoids resistance is made before the federal government requests that a military judge issue a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum. Provided that the federal government has proper jurisdiction over an accused, has referred charges against that accused to a properly convened general court-martial, and has filed a motion for appropriate relief, a military judge is empowered by the All Writs Act to issue a writ of habeas corpus ad prosquendum ordering the supervisor of a state confinement facility to deliver a state prisoner to federal agents for a court-martial. The writ is then immediately executed and the state has no power to refuse to turn over the prisoner. Because the prisoner is merely on loan—and never in the custody of the federal government—the prisoner must be returned to the state at the conclusion of the court-martial so that the prisoner can finish serving his state sentence. Absent a concurrent running of the sentence, once the Soldier has served his state sentence, he will be transferred to federal authorities to serve any remaining court-martial sentence.75 Finally, because the writ is not a detainer, there is no room for the state to disapprove the request and the federal government is not bound by the Interstate Agreement on Detainers Act’s restrictions and harsh penalties for non-compliance.76

The scenario presented at the beginning of this article is based on an actual case.77 The military preferred charges against that Soldier for conduct that occurred in Texas, Germany, and Virginia prior to Virginia authorities requesting the Soldier’s presence for a state trial. The Soldier returned to Virginia and was convicted of the charged crimes and sentenced to confinement in the Virginia state prison system.78 Trial counsel at Fort Riley coordinated with the installation Provost Marshal’s Office and Virginia authorities to see if there would be any resistance to the Army seeking the Soldier’s presence for court-martial. Using the steps outlined in this article, the trial counsel—after referral of the charges covering conduct that occurred in Texas and Germany—requested that the military judge issue a writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum.79 The military judge issued the writ and the U.S. Marshal Service ensured the prisoner’s transport to Fort Riley.80 Once at Fort Riley, the Soldier pled guilty to the charged offenses, was found guilty and sentenced, and was promptly returned to Virginia to continue serving his state sentence.81 Once the prisoner has served his state sentence, he will be transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to serve his federal sentence. TAL

CPT Wood is presently assigned as the Senior Attorney, Administrative and Civil Law, United States Military Academy, West Point, New York.

Notes

1. See Uniform Code of Military Justice arts. 2, 5 (2018) [hereinafter UCMJ].

2. See U.S. Dep’t of Army, Reg. 600-8-24, Officer Transfers and Discharges ch. 4 (12 Apr. 2006) (RAR, 13 Sept. 2011).

3. A writ of habeas corpus ad prosequendum is “a writ of habeas corpus which issues for the purpose of removing a prisoner in order to prosecute him in the proper jurisdiction.” Ballentine’s Law Dictionary (3d ed. 2010).

4. See Pub. L. No. 91-358, 84 Stat. 1397 (1970).

5. The All Writs Act is the common nomenclature used when referring to 28 U.S.C. § 1651 (2018).

6. See 28 U.S.C. § 1651 (2018). See also United States v. Frischholz, 16 U.S.C.M.A 150, 152 (1966) (stating that a “court established by Act of Congress” . . . includes courts other than those established by Congress under Article III).

7. See United States v. Denedo, 556 U.S. 904 (2009).

8. Id. at 904–05.

9. See Noyd v. Bond, 395 U.S. 683, 689 (1969). See also United States v. Snyder, 18 U.S.C.M.A 480, 483 (1969). See also Dettinger v. United States, 7 M.J. 216, 219 (C.M.A. 1979). See also Manual for Courts-Martial, United States, R.C.M. 1203 and 1204 (2019) [hereinafter MCM] (Collectively, these rules allow for the Court of Criminal Appeals and the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces to entertain petitions for extraordinary relief and issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their jurisdiction and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.).

10. Gagnon v. United States, 42 C.M.R. 1035, 1042 (A.F.C.M.R. 1970).

11. Id. at 1043 (citing Glidden Co. v Zdanok, 370 U.S. 530, 561 (1962)).

12. See Zamora v. Woodson, 19 U.S.C.M.A. 403, 404 (1970).

13. See UCMJ arts. 22 and 26 (2019); MCM, supra note 9, R.C.M. 504.

14. See UCMJ arts. 26 and 66 (2018). See also Pub. L. No. 90-632, 82 Stat. 1335 (1968).

15. See UCMJ arts. 66, 67, 67a (2018).

16. See Adams v. United States ex rel. McCann, 317 U.S. 269 (1942).

17. Id. at 273.

18. See Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266, 281–284 (1948).

19. Major Thomas Rankin, The All Writs Act and the Military Judicial System, 53 Mil. L. Rev. 103, 113 (1971).

20. United States v. Mauro, 436 U.S. 340, 357 (1978).

21. Id. at 358; see also 28 U.S.C. § 2241(c)(5) (2018) (discussing how a writ of habeas corpus should not extend to a prisoner unless it is necessary to bring him into court to testify or for trial).

22. See Stewart v. Bailey, 7 F.3d 384, 389 (4th Cir. 1993).

23. See Mauro, 436 U.S. at 357–358.

24. Stewart, 7 F.3d at 389.

25. Id. at 390.

26. See id. at 389.

27. See id.

28. See id.

29. See Jiron-Garcia v. Commw. of Va., 48 Va. App. 638, 648 (Va. Ct. App. 2006).

30. Stewart, 7 F.3d at 390.

31. See Jiron-Garcia, 48 Va. App. at 648.

32. See Benson v. St. Board of Parole and Probation, 384 F. 2d 238, 239 (9th Cir. 1968), cert. denied, 391 U.S. 954 (1968) (discussing how jurisdiction conferred by the All Writs Act is ancillary and dependent upon primary jurisdiction conferred by other statutes).

33. See MCM, supra note 9, R.C.M. 1107(d)(3)(A–C).

34. See United States v. Pleau, 680 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2012).

35. Id. at 6.

36. See id. at 3.

37. See id.

38. See United States v. Mauro, 436 U.S. 340, 357 (1978).

39. See Pleau, 680 F.3d at 7.

40. See Mauro, 436 U.S. at 343.

41. Id.

42. See id.

43. See id. at 352.

44. See id. at 349.

45. Id. at 351.

46. See id.

47. Id. at 352.

48. See id.

49. See id.

50. See id.

51. See id. at 353.

52. See 18 U.S.C. App. § 2, Articles III(d), IV(e), and V(c) (2018).

53. See Mauro, 436 U.S. at 351.

54. See id. at 352.

55. See id.

56. See id. at 349.

57. See id. at 351.

58. See id. at 351–52.

59. See id.

60. See id. at 353.

61. See MCM, supra note 9, R.C.M. 202 (court-martial jurisdiction over the person occurs when action with a view to trial is taken).

62. See Benson v. St. Board of Parole and Probation, 384 F. 2d 238, 239 (9th Cir. 1968), cert. denied, 391 U.S. 954 (1968).

63. See UCMJ art. 22 (2018); MCM, supra note 9, R.C.M. 201, 504, 601, 602.

64. See 1-13 Court-Martial Procedure § 13-10.00 (2016).

65. See UCMJ art. 39 (2018) (discussing how once referred charges has been served on the Accused, the military judge may consider motions in an Article 39(a) session).

66. See 28 U.S.C. § 1651 (2018).

67. See United States v. Snyder, 18 U.S.C.M.A 480, 483 (1969).

68. See 28 U.S.C. § 1651 (2018).

69. See Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266, 279 (1948).

70. See Bauman v. United States Dist. Court, 557 F.2d 650, 656 (9th Cir. 1977). See also Dew v. United States, 48 M.J. 639, 648–49 (Army Ct. Crim. App. 1998).

71. Price, 334 U.S. at 283.

72. See Jiron-Garcia v. Commw. of Va., 48 Va. App. 638, 648 (Va. Ct. App. 2006).

73. Jiron-Garcia, 48 Va. App. at 643.

74. Id.

75. See MCM, supra note 9, R.C.M. 1113(e)(2).

76. See Stewart v. Bailey, 7 F.3d 384, 389 (4th Cir. 1993); see also United States v. Pleau, 680 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2012).

77. United States v. Gumataotao, 2016 LEXIS 413, Army 20150765 (Army Ct. Crim. App. 22 Jun 2016) (mem. op.).

78. Virginia convicted the accused of fornication/incest with a child and aggravated sexual battery with a child. The accused was sentenced to serve twelve years confinement.

79. Gov’t Motion for Appropriate Relief: Government Request for Continuance and Writ of Habeas Corpus Ad Prosequendum, United States v. Gumataotao (3d Judicial Circuit, U.S. Army, 2015) (on file with author).

80. Writ of Habeas Corpus Ad Prosequendum, United States v. Gumataotao (3d Judicial Circuit, U.S. Army, 2015) (on file with author).

81. Major Gumataotao was charged with two specifications of willful disobedience of a superior officer in violation of Article 90, UCMJ, three specifications of lewd acts with a child in violation of Article 120b, UCMJ, and two specifications of sexual assault with a child in violation of Article 120, UCMJ. Major Gumataotao was sentenced to a dismissal and twenty years of confinement.