An aerial view of a portion of the Spratly Islands, all of which are contested features in the South China Sea. (Credit: hit1912-stock.adobe.com)

Competing Claims in the South China Sea

By Major Sean R. Tyler

The South China Sea is one of the most hotly disputed areas in the world. Due to its key location as a major trade route with abundant natural resources, Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam have all asserted competing sovereignty claims to portions of the South China Sea.1 Maritime features in the South China Sea are similarly disputed, with the claimant states frantically building installations on varied rocks, reefs, and other features to expand their exclusive economic zones.2

For the adjoining states, the region’s importance cannot be understated. The South China Sea is a large tropical ocean space covering an area of roughly 1.4 million square miles.3 Located between the mainland coast of Southeast Asia and the archipelagic island groups of the Philippines, Borneo, and Indonesia, it is one of the world’s most heavily trafficked waterways.4 Approximately one-third of the world’s maritime trade passes through the South China Sea every year, equating to an estimated $3.37 trillion in ship-borne commerce.5 More than 30 percent of global maritime crude oil trade (15 million barrels per day) and almost 40 percent of global liquefied natural gas trade (4.7 trillion cubic feet) moves through the South China Sea each year.6 The South China Sea, however, is not only a major trade route. It is also rich in natural resources and is estimated to contain approximately 11 billion barrels of oil, 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and other undersea resources.7 It is home to an area of globally significant biological diversity, accounting for an estimated 12 percent of the global fishing catch worth over $21 billion per year.8 The competing sovereignty claims, encompassing one of the world’s most important trade routes and abundant natural resources, makes the South China Sea a regional flashpoint.

However, these competing sovereignty claims are not just regional disputes. Over the last decade, the South China Sea also emerged as an arena of strategic competition between the United States and China.9 Observers in the United States are increasingly concerned that China is gaining effective control of the South China Sea through their extensive island building, base construction activities, and use of maritime forces to assert their sovereignty claims.10 The 2021 U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) China Military Power Report states that China’s outposts in the South China Sea are capable of supporting military operations and include advanced weapon systems.11 The report also notes that China deploys navy, coast guard, and civilian ships to maintain a presence in disputed areas to deny fishing and oil and gas exploration by rival claimants.12 Further, Hainan Island, an island province in the South China Sea at the southernmost part of China, is home to Yulin Navy Base.13 Yulin Navy Base is one of China’s most important military facilities, as it houses China’s growing fleet of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines—some of which are dedicated to launching nuclear weapons.14 Especially relevant from a military strategy standpoint, the deeper waters of the South China Sea are key for China’s submarine fleet. Those deeper waters allow access to the Pacific Ocean outside of the traditional access points through the East China Sea, which has a concentration of U.S. and Japanese anti-submarine forces.15

The 2022 National Security Strategy and 2022 National Defense Strategy highlight U.S. leaders’ concerns with China’s behavior. As expressed in the 2022 National Security Strategy, U.S. President Joseph R. Biden stated China “is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it.”16 Similarly, the 2022 National Defense Strategy lists four Defense priorities, with one specifically focused on defending the homeland from China’s growing multi-domain threat and another prioritizing preparation for potential conflict with China in the Indo-Pacific.17 Specifically focused on the South China Sea, U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken stated China’s coercive and intimidating tactics in the region are the greatest threat to the rules-based maritime order and freedom of navigation.18 Similarly, Admiral John C. Aquilino, Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, stated China’s unlawful sovereignty claim negatively impacts all the countries in the region and the United States must urgently execute a strategy of integrated deterrence.19

Consistent with these statements, U.S. leaders have also made statements in support of regional allies and partners. At a summit between the United States and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), President Biden underscored the U.S. commitment to the region and pledged to deepen cooperation with allies and partners to defend against threats to the international rules-based order and to promote a free and open Indo-Pacific.20 Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam are all ASEAN member states.21 Specifically regarding the Philippines, a phone conversation between Secretary Blinken and the Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs “stressed the importance of the Mutual Defense Treaty for the security of both nations, and its clear application to armed attacks against the Philippine armed forces, public vessels, or aircraft in the Pacific, which includes the South China Sea.”22

As an area of strategic, political, military, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners, it is imperative that judge advocates (JAs) advising on operational and international law understand the South China Sea. In such a complex environment, a U.S. freedom of navigation operation could escalate into an international conflict.23 Similarly, a territorial dispute in the South China Sea between China and the Philippines could draw the United States into a conflict due to Mutual Defense Treaty obligations.24

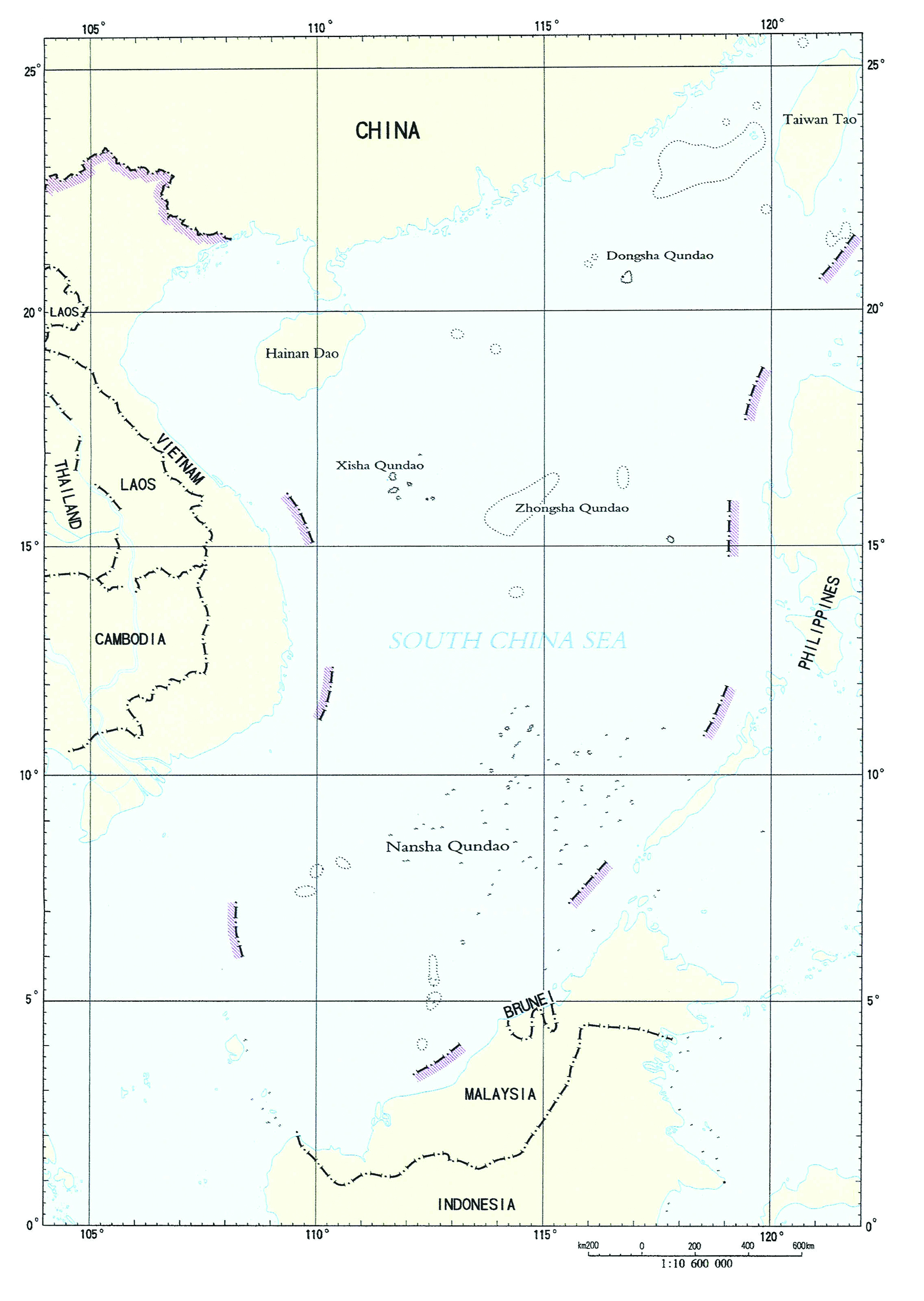

Figure 1. Sovereignty Claims in the South China Sea25

To provide JAs a baseline understanding of this complicated region, this article describes the major players in the South China Sea, the various sovereignty claims in the South China Sea, and the current international legal status of those claims. Specifically, it provides an overview of customary international law relating to maritime zones and features and navigational regimes, which are codified in the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Law of the Sea. It then describes the competing maritime sovereignty claims in the South China Sea, the 2016 Philippines-China arbitration ruling, and the current state of affairs post-arbitration. Finally, it provides an overview of the principal features in the South China Sea and the outposts each claimant placed on these features.

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea

Background

To provide legal context to this article’s discussion of the South China Sea, this background provides an overview of relevant customary international law26 and its eventual codification by treaty. Traditionally, the oceans were “classified under the broad headings of internal waters, territorial seas, and high seas.”27 “In the latter half of the twentieth century, new concepts evolved, . . . such as the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and archipelagic waters, . . . that dramatically expanded the jurisdictional claims of coastal and island states over wide expanses of the oceans previously regarded as high seas.”28 These expanding maritime jurisdictions entered international negotiation between 1973 and 1982 during the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea.29 That conference produced the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).30 To date, there are 169 state parties to UNCLOS.31

The United States was a driving force in these negotiations and a major proponent of a comprehensive treaty, but it never actually ratified UNCLOS due to concerns over its deep seabed mining provisions.32 Still, the United States generally considers the rest of UNCLOS to be a reflection of customary international law, or “existing maritime law and practice.”33 All South China Sea claimant states are state parties to UNCLOS except for Taiwan.34 Taiwan is not recognized by the UN and cannot be a party to UNCLOS, but it generally follows its provisions.35 Presently, UNCLOS is “the globally recognized regime addressing all matters related to the law of the sea.”36 Especially relevant to this article, it defines the maritime zones and associated navigational regimes, defines the various maritime features, and establishes international institutions to help interpret those provisions.

Maritime Zones and Associated Navigational Regimes

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea permits coastal states to establish several different maritime zones. These maritime zones are intended to balance a coastal state’s right to regulate and exploit ocean areas and natural resources under their jurisdiction with the navigational rights of all states.37 Maritime zones are drawn using “baselines,” which UNCLOS generally defines as “the low-water line along the coast as marked on large-scale charts officially recognized by the coastal [s]tate.”38 Figure 2 below displays the primary maritime zones.

Figure 2. Legal Boundaries of the Oceans and Airspace39

First, internal waters are all waters landward of the baseline (such as lakes, rivers, and tidewaters).40 Next, a state may claim a territorial sea measured seaward up to twelve nautical miles from their baseline, which is subject to its sovereignty.41 Contiguous zones then extend seaward from the baseline up to twenty-four nautical miles; they exist to bolster a state’s law enforcement capacity and prevent criminals from fleeing the territorial sea.42 Within the contiguous zone, the coastal state has the right to both prevent and punish infringement of fiscal, immigration, sanitary, and customs laws.43 Additionally, an EEZ is a resource-related zone that a state can claim.44 An EEZ extends seaward from the baseline up to 200 nautical miles and the coastal state has the exclusive right to exploit or conserve any resources found within the water, on the sea floor, or under the sea floor’s subsoil.45 Finally, high seas include all parts of the ocean seaward of the EEZ and are open to all states.46

For operational purposes, the waters of these maritime zones can be divided into two parts. While not legal terms of art, the international community widely accepts47 the distinction of these parts as “national waters” and “international waters.”48 Using the term “international waters” helps avoid confusion between the UNCLOS zone “high seas” and other UNCLOS zones (such as the contiguous zone and EEZ) where states enjoy “high seas freedom of navigation”49 in accordance with customary international law.

The first part, national waters, includes internal waters and territorial seas. These waters are subject to state sovereignty with certain navigational rights reserved to the international community.50 Ships (but not aircraft) of all states enjoy the right of innocent passage for the purpose of continuous and expeditions traversing territorial seas.51 “Passage is innocent so long as it is not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal [s]tate.”52 The second part, international waters, includes the contiguous zone, EEZ, and high seas.53 These are international waters where all states enjoy the freedoms of navigation and overflight.54

Another maritime area is the continental shelf. Unlike the maritime areas described above, which generally relate to the water, a continental shelf “comprises the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond [a state’s] territorial sea.”55 It extends either to the continental margin, or for a distance of 200 nautical miles from the baseline where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that distance not to exceed 350 nautical miles from the territorial sea baselines.56 The coastal state has the exclusive right to explore and exploit the continental shelf’s natural resources (mineral and other non-living resources and sedentary living resources).57

Maritime Features

Maritime zones are determined starting with the baseline of the coastal state; however, maritime features can affect how these zones are drawn. In the South China Sea dispute, the relevant maritime features are islands, rocks, and low-tide elevations. Artificial islands, installations, or structures are disputed in the South China Sea as well. “An island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide” and can sustain human habitation or economic life.58 Islands generate the same maritime zones as other landmasses, including a territorial sea, contiguous zone, EEZ, and continental shelf.59

A rock is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide but cannot sustain human habitation or economic activity.60 Unlike islands, rocks only generate a territorial sea and contiguous zone.61 “A low-tide elevation is a naturally formed area of land,” which is “above water at low tide but submerged at high tide.”62 Low-tide elevations do not generate maritime zones on their own, but if a low-tide elevation is within a state’s territorial sea, then that state may draw a baseline from the low-water line of the low-tide elevation rather than from the shore.63

In an EEZ, a coastal state has the exclusive right to construct, operate, and use artificial islands or structures.64 These artificial structures are typically built on low-tide elevations that are attached to the coastal state’s continental shelf. These artificial structures do not possess the status of islands, have no territorial sea of their own, and their presence does not affect the delimitation of the territorial sea, EEZ, or continental shelf.65 A coastal state is also permitted to create a safety zone of up to 500 meters to ensure safety of navigation and safety of the artificial structure.66

Excessive Maritime Claims and Freedom of Navigation Operations

Excessive maritime claims are “attempts by coastal [s]tates to unlawfully restrict . . . freedoms of navigation and overflight [and] other lawful uses of the sea.”67 These claims are generally made through domestic laws, regulations, or other pronouncements that are inconsistent with UNCLOS.68 Examples of excessive maritime claims include claiming a territorial sea on a low-tide elevation or requiring authorization for innocent passage of warships through a territorial sea.

The U.S. Freedom of Navigation Program upholds the U.S. policy of exercising and asserting its navigation and overflight rights and freedoms around the world.69 The program consists of both diplomatic and operational efforts.70 The Department of State protests excessive maritime claims through diplomatic communications.71 The DoD exercises U.S. “maritime rights and freedoms by conducting operational challenges against excessive maritime claims.”72 For example, as a persistent objector to China’s expansive maritime claims, the United States (and other nations)73 consistently conducts operational challenges throughout the South China Sea.74 These challenges are conducted to avoid Chinese claims from becoming established state practice.75 The classification of maritime features under UNCLOS, and the maritime zones they generate, is a focal point for many disputes over excessive maritime claims.76 Understanding that states would interpret these provisions differently, and that varied interpretations could lead to disputes, UNCLOS established three new international institutions to aid in its application.

International Institutions Established by UNCLOS

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea established the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (the tribunal),77 the International Seabed Authority (the authority),78 and the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (the commission).79 The following section focuses on the commission as it is relevant to the competing sovereignty claims in the South China Sea.

The commission principally examines and makes recommendations on coastal state claims of an extended continental shelf.80 When a state intends to establish the outer limits of its continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, it must submit “supporting scientific and technical data” to the commission for review.81 The commission consists of twenty-one members that UNCLOS member states elect.82 These members are experts in geology, geophysics, or hydrography, and they serve in their personal capacity.83 The commission reviews the submission and provides a recommendation back to the state.84 If the state then establishes its extended continental shelf outer limits based on the commission’s recommendation, those outer limits are “final and binding.”85 It is important to note that “actions of the commission shall not prejudice matters relating to delimitation of boundaries between [s]tates with opposite or adjacent coasts.”86 As discussed below, China frequently points to this provision when arguing that UNCLOS and the commission do not apply to the South China Sea sovereignty dispute. The following section provides an overview of the varied submissions to the commission and the ensuing diplomatic disputes.

Sovereignty Disputes

Background

Between 2009 and 2019, the commission received three submissions significant to the sovereignty disputes in the South China Sea. These submissions and the Philippines-China arbitration (addressed below) shape the current political and legal landscape of the disputes. The submissions include the 2009 Joint Submission by Malaysia and the Philippines,87 the 2009 Partial Submission by Vietnam,88 and the 2019 Partial Submission by Malaysia.89 To date, the commission has not acted on any of the submissions due to the contentious nature of the sovereignty claims between these states with opposite or adjacent coasts.90 Still, the diplomatic communications provide an outline of the varied legal claims to this heavily disputed area.

2009 Submissions to the Commission

The 2009 Joint Submission by Malaysia and the Philippines and the 2009 Partial Submission by Vietnam both claimed extended continental shelfs.91 These submissions are especially important because they triggered China to formally present the U-shaped “nine-dash line” concept to the international community for the first time; on 7 May 2009, China communicated two diplomatic notes to the UN Secretary-General objecting to both submissions.92 The Chinese notes stated:

China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof . . . . The above position is consistently held by the Chinese Government, and is widely known by the international community.93

Figure 3 below includes the map that China attached to these submissions.

Figure 3. China’s “Nine-Dash Line” Map from Notes Verbales of 7 May 200994

China’s claims prompted a flurry of responses from neighboring states.95 Vietnam countered that the nine-dash line has no “legal, historical or factual basis, therefore is null and void.”96 Vietnam further stated that the Paracel Islands and Spratly Islands “are parts of [Vietnam],” over which it has “indisputable sovereignty.”97 Similarly, the Philippines claimed sovereignty over the “Kalayaan Island Group” (located in the northeastern section of the Spratly Islands).98 On 14 April 2011, China responded to the Philippines and stated the Philippines claims are “totally unacceptable.”99 The response stated that the “so-called Kalayaan Island Group (KIG) claimed by the Republic of Philippines is in fact part of China’s Nansha Islands,” and that the Philippines’ “occupation of some islands and reefs of China’s Nansha Islands” infringes on their sovereignty.100 The note continued that China’s Nansha Islands are fully entitled to a territorial sea, EEZ, and continental shelf.”101 On 3 May 2011, Vietnam reiterated their claims to both the Paracel and Spratly Islands.102 These diplomatic disputes and increased Chinese activity throughout the South China Sea led the Philippines to seek formal dispute resolution with China under UNCLOS.

Philippines-China Arbitration

On 22 January 2013, the Philippines initiated arbitral proceedings against China under UNCLOS Annex VII.103 Generally, the Philippines requested arbitration on China’s nine-dash line historic rights claim, the status of several maritime features in the South China Sea and the entitlements they are capable of generating, and the lawfulness of certain Chinese actions (including land reclamation, building artificial islands, and blocking Filipino fishing and oil exploration activities).104 China refused to participate in the arbitration and stated that any tribunal established to decide these issues would have no jurisdiction.105 China’s main argument against jurisdiction was that the essence of the arbitration was territorial sovereignty over South China Sea maritime features (land, not water), which does not concern the interpretation or application of UNCLOS.106 However, when there is a dispute “as to whether a court or tribunal has jurisdiction, the matter shall be settled by decision of that court or tribunal.”107

Following this provision, a five-judge tribunal under the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague constituted to consider the matter.108 The tribunal’s jurisdiction determination rested on whether the dispute concerned the interpretation or application of UNCLOS.109 Contrary to China’s argument, the tribunal determined that UNCLOS applied and it had jurisdiction over the dispute.110 Specifically, the tribunal determined it could assess the Philippines’ claims without determining territorial sovereignty of the maritime features in the South China Sea.111

On 12 July 2016, the tribunal released its award.112 It ruled against China on most issues.113 The tribunal concluded that China’s nine-dash line historic rights claim is invalid.114 The tribunal also concluded that neither Scarborough Shoal nor any of the high-tide features in the Spratly Islands in their natural condition “are capable of sustaining human habitation or an economic life on their own.”115 Therefore, these features are “legally rocks for purposes of Article 121(3) and do not generate entitlements to an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.”116 Finally, the tribunal concluded that China’s land reclamation, artificial island building, and use of maritime forces to block Filipino fishing and oil exploration violated UNCLOS and infringed upon the Philippines’ sovereign rights in the Filipino EEZ.117

As a state party to UNCLOS, China is legally bound by the tribunal’s decision. However, China promptly rejected the lawfulness of the award. On the day of the award, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated the ruling was “null and void.”118 The day after the award, it released a white paper that insisted, “In addition [to internal waters, territorial sea, contiguous zone, EEZ and continental shelf], China has historic rights in the South China Sea.”119 To date, China refuses to comply with the award.120 The difficulty for the international community is that there is no enforcement mechanism. China took the “might trumps right” approach, and the international community is now left where they were before the arbitration. Not surprisingly, the tribunal’s award and China’s noncompliance laid the groundwork for another diplomatic dispute at the commission.

2019 Submission to the Commission

On 12 December 2019, Malaysia submitted the first post-arbitration communication to the commission.121 It was a partial submission outlining the northern part of its purported extended continental shelf.122 While not specifically mentioned, Malaysia implicitly endorsed the award by stating “the subject of this [p]artial [s]ubmission . . . is not located in an area which has any land or maritime dispute between Malaysia and any other coastal [s]tate.”123 This 2019 submission renewed the South China Sea legal debate and prompted a flurry of diplomatic responses from both claimant states and other interested parties.124

China’s response to Malaysia did not mention the nine-dash line but instead claimed sovereignty over “Nanhai Zhudao” (basically all the islands of the South China Sea), which they claim generates an EEZ and a continental shelf.125 The Philippines then responded to China, claiming for itself both the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal, dismissing the Chinese historic rights claims, and citing the award’s decision that no maritime feature in the Spratly Islands are high-tide features generating an EEZ or continental shelf.126

In response to the Philippines, China stated it “neither accepts nor participates in the South China Sea arbitration, neither accepts nor recognizes the awards, and will never accept any claim or action based on the awards.”127 Vietnam responded to China, claimed both the Paracel Islands and Spratly Islands, and, while not specifically mentioning the award, also stated that the South China Sea maritime features “do not, in and of themselves, generate entitlements to any maritime zones.”128 In response to Vietnam, China stated Vietnam is violating its sovereign rights to the Spratly Islands and demanded that “Vietnam withdraw all the crews and facilities from the islands and reefs it has invaded and illegally occupied.”129

The diplomatic exchanges, however, were not limited to South China Sea claimant states. Listed chronologically, other countries also provided notes, including: Indonesia; the United States; Australia; a joint submission from the United Kingdom, France, and Germany; Japan; and New Zealand.130 Generally, these notes stated that China must comply with the tribunal award, China’s historic rights claims are illegal, and no maritime feature in the South China Sea generates an EEZ or continental shelf.131 The 1 June 2020 letter from the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Secretary-General stated:

In asserting such vast maritime claims in the South China Sea, China purports to restrict the rights and freedoms, including the navigational rights and freedoms, enjoyed by all [s]tates. The United States objects to these claims to the extent they exceed the entitlements China could claim under international law as reflected in the Convention.132

The United States further clarified its position one month later when Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo outlined the U.S. policy regarding maritime claims in the South China Sea.133 Specifically, Secretary Pompeo noted that the “Arbitral Tribunal’s decision is final and legally binding on both parties” and that “[t]oday we are aligning the U.S. position on [China’s] maritime claims in the [South China Sea] with the tribunal’s decision.”134 The policy further denounced China’s regional “bullying,” highlighted the tribunal award, and stated that “America stands with our Southeast Asian allies and partners in protecting their sovereign rights to offshore resources, consistent with their rights and obligations under international law.”135 On 11 July 2021, Secretary Blinken reaffirmed the policy under the Biden Administration.136

China, however, consistently holds to its “legal” position. In every submission where a country criticized a Chinese claim, China provided a note in response.137 Since Malaysia’s Partial Submission, China has provided eleven responsive diplomatic notes.138 In response to the U.S. letter, China opposed the “completely wrong accusations made by the United States,” maintained their historical rights claims, and stated it complies with UNCLOS.139 The Annex to their response concluded by stating:

China also urges the United States not to cause troubles in the South China Sea, not to conduct military provocation and not to sow discord between China and ASEAN countries, but to fully respect China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea, and to respect the joint efforts made by China and ASEAN countries to maintain peace and stability in the South China Sea.140

Diplomatically, China vociferously defends their claim to the South China Sea. Over the last decade, however, China paired this diplomatic pressure with an increased military capability.

Figure 4. Occupied Features in the South China Sea141

Figure 5. Chinese Military Features on Contested Features in the South China Sea.142

China militarized artificial islands built on their occupied features to bolster control over the disputed waters. While China does not control all the features in the South China Sea, the ones it does control are exponentially more developed and capable of projecting power. Figure 4 above provides the locations of all the occupied outposts in the South China Sea. Figure 5 above displays the Chinese-occupied features and their military capabilities. To aid in understanding how China uses this military strength to further their sovereignty claims, the following section discusses what entities claim the relevant maritime features, what entities actually control them, and what the United States does to protest what it deems as excessive maritime claims.

Occupied Features in the South China Sea

Background

Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam all assert sovereignty over maritime features in the South China Sea.143 Brunei has yet to occupy any contested feature, but the other five claimants collectively occupy nearly seventy disputed features and have built more than ninety outposts on these contested features. The Chinese outposts are especially developed, and China claims, contrary to the tribunal’s award, they generate territorial seas, EEZs, and continental shelfs. As discussed above, China continues to claim almost the entirety of the South China Sea based on territorial sovereignty over the maritime features.144 Within the last five years, in response to these excessive maritime claims, the United States conducted thirty-one freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea.145 Figure 6 below shows these operations and summarizes instances of U.S.-China military interactions. Each occupied outpost is described in detail below to highlight their military capabilities and underscore the seriousness of U.S. freedom of navigation operations in the area. Of note, while many of the maritime features discussed below are named “islands,” the name does not square with their legal nature (as most are not islands but rocks and low-tide elevations).

Figure 6. Approximate Reported Locations of Some Freedom of Navigation Operations since 2016146

Paracel Islands

The Paracel Islands “are located in the northeast corner of the South China Sea, approximately equidistant from the [eastern] coast of Vietnam and the [southeast coast of the] Chinese island of Hainan.”147 They are “composed of 130 small coral islands and reefs divided into the northeast Amphitrite Group and the western Crescent Group.”148 China, Taiwan, and Vietnam all claim sovereignty over the Paracel Islands.149 China, however, has occupied the Paracel Islands since 1974, when they forcibly ejected Vietnamese troops from the western Crescent Group.150 In ousting these Vietnamese troops, China consolidated control of both island groups, as they already occupied the northeast Amphitrite Group.151

China maintains twenty outposts in the Paracel Islands.152 To date, they remain the only state with any outposts in this location.153 Woody Island, China’s administrative center for the Paracel Islands, is the largest base with over 1,000 residents, and “includes an airstrip with fighter aircraft hangars, naval facilities, surveillance radars, and defenses such as surface-to-air missiles and anti-ship cruise missiles.”154 Seven other outposts also have military characteristics such as helipads and protected harbors.155

Spratly Islands

The Spratly Islands are in the eastern South China Sea, west of the Philippine island of Palawan and northeast of the island of Borneo.156 They are composed of more than 100 reefs, rocks, shoals, and sandbanks.157 China, Taiwan, and Vietnam claim the Spratly Islands in their entirety.158 Malaysia and the Philippines claim specific portions.159 Brunei also informally claims a small portion that overlaps a southern reef.160

China

China maintains seven outposts in the Spratly Islands.161 From 2013 to 2015, China engaged in unprecedented dredging and artificial island-building for these outposts, creating 3,200 acres of new land by late 2015.162 The other South China Sea claimants reclaimed only 172 acres over the past forty years.163 Specifically, Vietnam reclaimed approximately 80 acres; Malaysia, 70 acres; the Philippines, 14 acres; and Taiwan, 8 acres.164 Thus, China’s two years of reclamation work accounts for 95 percent of all reclaimed land in the Spratly Islands.

Since 2015, however, China generally stopped the land reclamation efforts and focused on completing their military infrastructure.165 In September 2015, China’s President, Xi Jinping, made a public commitment not to “militarize” these artificial islands, but satellite images show otherwise.166 The four small outposts on Cuarteron, Gaven, Hughes, and Johnson reefs contain administrative buildings, weapon stations, and sensor emplacements.167 The three large outposts on Fiery Cross, Mischief, and Subi reefs have established air bases with runways, helipads, and aircraft hangars.168 The aviation improvements on these outposts give China the capacity to house up to three regiments of combat aircraft.169 Currently, no large-scale presence of combat aircraft has been observed.170 However, future deployments of combat aircraft operating from these outposts could feature extended range and loiter time over the South China Sea or even reach into the Indian Ocean.171

These outposts also have naval port facilities, surveillance radars, air defense and anti-ship missile sites, and other military infrastructure such as communications, barracks, maintenance facilities, and ammunition and fuel bunkers.172 In 2018, the outposts were equipped with advanced anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems and military jamming equipment.173 In 2020, China deployed KJ-200 anti-submarine warfare and KJ-500 airborne early warning aircraft to Fiery Cross Reef.174 The militarization of these outposts, and the corresponding capacity to project power, bolsters China’s ability to defend their sovereignty claims over the entirety of the South China Sea.

Taiwan

Taiwan has one outpost in the Spratly Islands—Itu Aba Island.175 Taiwan constructed a runway, helipad, pier, and several administrative buildings on Itu Aba Island.176 It is the largest natural feature in the Spratly Islands and arguably the only feature in the entire South China Sea with a natural water source.177 Still, the tribunal concluded that no feature in the Spratly Islands, to include Itu Aba Island, can legally be categorized as an island under UNCLOS because none are “capable of sustaining human habitation or an economic life on their own.”178 Taiwan, however, still argues for island status. The focus of their argument is their four freshwater wells, natural vegetation (banana and coconut trees), and small vegetable gardens.179

Vietnam

Vietnam maintains outposts on twenty-seven features in the Spratly Islands.180 Spratly Island itself is the largest Vietnamese outpost, and the only Vietnamese outpost with a runway.181 Spratly Island also has aircraft hangars, naval port facilities, administrative buildings, weapon stations, and sensor emplacements.182 Several other outposts are similarly established, but have helipads instead of a runway.183 Other outposts are basically concrete buildings built atop reefs.184 These outposts are generally referred to as “pillboxes,” and consist of between one and four separate concrete structures connected by bridges, often with jetties allowing small boats to dock.185 Vietnam also has isolated outposts known as “economic, scientific, and technological service stations,” or Dịch vụ-Khoa (DK1) structures, built at six other locations.186 These DK1 stations are generally one- or two-story buildings built on steel trusses to house a small garrison of troops and are topped with a helipad.187

Malaysia

Malaysia maintains five outposts in the southern part of the Spratly Islands.188 Swallow Reef has a runway, helipad, and aircraft hangars.189 The other outposts all have helipads.190

The Philippines

The Philippines occupies nine features in the Spratly Islands.191 Thitu Island is the most established feature and is the administrative center of the Philippine municipality of Kalayaan.192 It has a mayor and functions as the seat of local government for the other eight features the Philippines occupies.193 Thitu Island also has a small town (approximately 200 people) composed mostly of members of the Filipino military and their families.194 Thitu Island has a runway, naval port facilities, and other administrative buildings.195 The other eight features are only minimally improved.196 Second Thomas Shoal, where the Philippines intentionally grounded the BRP Sierra Madre (a U.S. Navy landing ship from World War II transferred to the Philippines after the Vietnam War) in 1999, serves as a military outpost and base for a rotating force of Filipino Marines.197

Brunei

Two features in the Spratly Islands are located within Brunei’s South China Sea maritime claim (Louisa Reef and Riflemen Bank), but Brunei has never established an outpost on either feature.198 Malaysia also claimed Louisa Reef, but that dispute was seemingly resolved in favor of Brunei when the two countries’ leaders met in 2009.199 Rifleman Bank (which includes Bombay Castle, Kingston Shoal, and Orleana Shoal) is an undersea bank where Vietnam established isolated DK1 platforms as “economic, scientific, and technological service stations.”200

Pratas Islands

The Pratas Islands are located in the northern part of the South China Sea, approximately 170 nautical miles southeast of Hong Kong and 260 nautical miles southwest of Taiwan.201 Taiwan maintains the only outpost in the Pratas Islands, which contains a military airport and administrative buildings.202 China also claims sovereignty over the Pratas Islands, but states no competing claims exist since “China treats Taiwan as its integral part.”203

Macclesfield Bank

Macclesfield Bank, located to the east of the Paracel Islands, is a permanently submerged feature with no outposts.204 Both China and Taiwan claim sovereignty over the area.205 Similar to the Pratas Islands, China states no competing claims exist as “China treats Taiwan as its integral part.”206

Scarborough Shoal

Scarborough Shoal is an unimproved rock located “120 nautical miles west of the Philippine island of Luzon.”207 China, Taiwan, and the Philippines all claim Scarborough Shoal.208 While considered inside the Philippines’ EEZ, China has effectively controlled it for almost ten years.209 To maintain control of Scarborough Shoal, China permanently anchored several coast guard ships and consistently deploys navy, coast guard, and civilian ships to increase their presence.210 The Chinese presence deters Filipino fishermen, whose livelihood depends on fishing the abundant waters around the shoal.211

Conclusion

The South China Sea is now an area of strategic competition. China’s increased assertiveness and the U.S. shift to the Indo-Pacific make this matter especially relevant to JAs practicing international and operational law in the region. Judge advocates need to understand the South China Sea’s major players, the various sovereignty claims, and the current international legal status of each claim. This is especially relevant when advising on freedom of navigation operations, because China uses their military to enforce their excessive maritime claims. If there are any questions, JAs should seek guidance up the chain of command to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Office of the Staff Judge Advocate. Further, China’s artificial islands now have the capacity to house at least three regiments of combat aircraft and are equipped with advanced anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems as well as military jamming equipment.

The competing claims in the South China Sea are also relevant to JAs stationed outside the Indo-Pacific. While the tribunal award invalidated the Chinese nine-dash line claim, China continues to maintain historic rights arguments over the South China Sea and uses control over maritime features to bolster their claims. In response, the United States committed to defending its regional allies, the international rules-based order, and a free and open Indo-Pacific. A conflict between China and a rival claimant could quickly escalate to the global stage, and JAs must understand this complex dispute. TAL

Maj Tyler is the Deputy Staff Judge Advocate for 1st Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California.

Notes

1. See Lori Fisler Damrosch & Bernard H. Oxman, Agora: The South China Sea: Editors’ Introduction, 107 Am. J. Int’l L. 95 (2013); see also Maritime Claims of the Indo-Pacific, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/maritime-claims-map (last visited Dec. 4, 2023) (showing maritime claim boundaries through an interactive map and listing the documents to which each country cites for their claim).

2. Occupation and Island Building, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/island-tracker (last visited Dec. 4, 2023).

3. Beina Xu, South China Sea Tensions, Council on Foreign Rels. (May 14, 2014, 8:00 AM), https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/south-china-sea-tensions.

4. Ben Dolven et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., IF10607, China Primer: South China Sea Disputes 1 (2021).

5. How Much Trade Transits the South China Sea, ChinaPower, https://chinapower.csis.org/much-trade-transits-south-china-sea (last visited Dec. 4, 2023). The global economy is heavily dependent on shipping. The United Nations (UN) Conference on Trade and Development estimates that approximately 80 percent of global trade by volume is transported by sea. See U.N. Conf. on Trade and Dev., Review of Maritime Transport 21 (2020).

6. More than 30% of Global Maritime Crude Oil Trade Moves Through the South China Sea, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (Aug. 27, 2018), https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=36952; Almost 40% of Global Liquefied Natural Gas Trade Moves Through the South China Sea, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (Nov. 2, 2017), https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=33592.

7. South China Sea, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (Oct. 15, 2019), https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/regions-of-interest/South_China_Sea.

8. Rashid Sumaila &William Cheung, Boom or Bust: The Future of Fish in the South China Sea 3 (2016). The authors also note that this is only the “landed value” and believe the numbers would be significantly higher if “unreported catches” were included. Id. at 3-4.

9. Ronald O’Rourke, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R42784, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress 1 (2023).

10. See id. at 1-3.

11. See U.S. Dep’t of Def., Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 103 (2021) [hereinafter 2021 China Military Power Report].

12. Id. at 18, 80-81, 121.

13. See A Glimpse of Chinese Ballistic Missile Submarines, Ctr. for Strategic & Int’l Studs. (Aug. 4, 2021), https://www.csis.org/analysis/glimpse-chinese-ballistic-missile-submarines (noting that China’s Type 094 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine carries missiles that, if launched from waters near China, could threaten Guam, Hawaii, and Alaska).

14. Id.; 2021 China Military Power Report, supra note 11, at 49.

15. Geography Will Drive China’s Navy into South China Sea, Oxford Analytica (Feb. 11, 2016), https://dailybrief.oxan.com/Analysis/GA208397/Geography-will-drive-Chinas-navy-into-South-China-Sea.

16. The White House, National Security Strategy 23 (2022).

17. U.S. Dep’t of Def., 2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America 7 (2022).

18. Press Release, Antony J. Blinken, U.S. Sec’y of State, Fifth Anniversary of the Arbitral Tribunal Ruling on the South China Sea (July 11, 2021), https://www.state.gov/fifth-anniversary-of-the-arbitral-tribunal-ruling-on-the-south-china-sea.

19. C. Todd Lopez, U.S. Will Continue to Operate in South China Sea to Ensure Prosperity for All, U.S. Dep’t of Def. (Aug. 4, 2021), https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2720047/us-will-continue-to-operate-in-south-china-sea-to-ensure-prosperity-for-all. Integrated deterrence is the U.S. Department of Defense approach to preventing conflict through the synchronization of all elements of national power, with joint force actions in all domains, together with allies and partners. See Hearing to Receive Testimony on the Posture of United States Indo-Pacific Command Before the Senate Committee on Armed Services, 117th Cong. (2022) (statement by Admiral John Aquilino, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command).

20. Press Release, White House, Readout of President Biden’s Participation in the U.S.-ASEAN Summit (Oct. 26, 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/10/26/readout-of-president-bidens-participation-in-the-u-s-asean-summit.

21. ASEAN Member States, Ass’n of Se. Asian Nations, https://asean.org/member-states (last visited Dec. 5, 2023).

22. Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of State, Secretary Blinken’s Call with Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs Locsin (Jan. 27, 2021), https://www.state.gov/secretary-blinkens-call-with-philippine-secretary-of-foreign-affairs-locsin.

23. This is even the premise for 2034: A Novel of the Next World War, a popular fictional book written by Admiral James Stavridus and Elliot Ackerman. Elliot Ackerman & James G. Stavridis, 2034: A Novel of the Next World War (2021).

24. Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines, Phil.-U.S., Aug. 30, 1951, 3 U.S.T. 3947.

25. Fisler Damrosch & Oxman, supra note 1, at 96.

26. “Customary international law results from a general and consistent practice of states followed out of a sense of international legal right or obligation.” Restatement (Fourth) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States § 404(b), at 149 (Am. L. Inst. 2018).

27. U.S. Dep’t of Navy et al., NWP 1-14M, The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations para. 1-1 (Mar. 2022) [hereinafter Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations].

28. Id.

29. Id.

30. U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397 [hereinafter UNCLOS].

31. See Chronological Lists of Ratifications of Accessions and Successions to the Convention and the Related Agreements, Div. for Ocean Affs. & L. of the Sea, United Nations (Oct. 24, 2023), https://www.un.org/depts/los/reference_files/chronological_lists_of_ratifications.htm.

32. See Law of the Sea Convention, Dep’t of State, https://www.state.gov/law-of-the-sea-convention (last visited Dec. 6, 2023) (providing a timeline for U.S. action on UNCLOS and links to key statements and documents). Further negotiations resulted in an additional agreement regarding Part XI (covering the deep seabed), which the United States signed on 29 July 1994. See Agreement Relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982, July 28, 1994, 1836 U.N.T.S. 3. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee voted UNCLOS out of Committee in both 2004 and 2007, but the full Senate never acted on the Committee’s recommendations. See Law of the Sea Convention, supra. New hearings were held in 2012, but later suspended. Id. To date, no further action has been taken. See id.; Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, supra note 27, para. 1-1.

33. Statement on United States Oceans Policy, Ronald Reagan Presidential Lib. & Museum (Mar. 10, 1983), https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/statement-united-states-oceans-policy.

34. The dates of ratification of these five claimant states are as follows: Brunei, 5 November 1996; China, 7 June 1996; Malaysia, 14 October 1996; the Philippines, 8 May 1984; and Vietnam, 25 July 1994. See U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, Status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Agreement Relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the Convention and the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the Convention Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, as at 31 July 2019, at tbl.1 (2019), https://www.un.org/depts/los/reference_files/UNCLOS%20Status%20table_ENG.pdf (listing all member states and their participation in UNCLOS).

35. See Huynh Tam Sang, UNCLOS’s Relevance to Taiwan Amid a Raging Storm, FULCRUM (Oct. 4, 2022), https://fulcrum.sg/uncloss-relevance-to-taiwan-amid-a-raging-storm; G.A. Res. 2758 (Oct. 25, 1971) (the U.N. General Assembly decided “to restore all its rights to the People’s Republic of China and to recognize the representatives of its Government as the only legitimate representatives of China to the [UN], and to expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek [(former leader of the Republic of China)] from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the [UN] and in all the organizations related to it”).

36. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982: Overview and Full Text, U.N. Div. for Ocean Affs. & L. of Sea (July 21, 2023), https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_overview_convention.htm.

37. Chapter 2: Maritime Zones, Law of the Sea: A Policy Primer, Tufts Univ., https://sites.tufts.edu/lawofthesea/chapter-two (last visited Dec. 6, 2023).

38. UNCLOS, supra note 30, pt. II, art. 5.

39. Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, supra note 27, at 1-3.

40. UNCLOS, supra note 30, pt. II, art. 8.

41. Id. pt. II, art. 3.

42. See id. pt. II, art. 33.

43. Id.

44. Id. pt. V, arts. 55, 56.

45. Id. pt. V, arts. 56, 57.

46. Id. pt. VII, arts. 86, 87.

47. See, e.g., Oceans: The Lifeline of our Planet: Anniversary of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: 20 Years of Law and Order on the Oceans and Seas (1982-2002), U.N. Div. for Ocean Affs. & L. of Sea, https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_20years/oceansthelifeline.htm (last visited Dec. 6, 2023) (“One of the most fundamental achievements reached during the negotiations and reflected in UNCLOS was a consensus on the line separating national and international waters where all [s]tates can exercise freedom of navigation, which up until this time had been a major bone of contention among coastal [s]tates. UNCLOS established a 12-nautical mile territorial sea, within which [s]tates are free to enforce any law, regulate any use and exploit any resource.”); S.C. Res. 1801 § 12 (Feb. 20, 2008) (“Encourages [m]ember [s]tates whose naval vessels and military aircraft operate in international waters and airspace adjacent to the coast of Somalia to be vigilant to any incidents of piracy therein and to take appropriate action to protect merchant shipping . . . .”); S.C. Res. 552 § 2 (June 1, 1984) (“Reaffirms the right of free navigation in international waters and sea lanes for shipping en route to and from all ports and installations of the littoral [s]tates that are not parties to the hostilities . . . .”).

48. See Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, supra note 27, paras. 2.5, 2.6 (providing overviews of navigation in and overflight of national and international waters).

49. See Off. of Staff Judge Advoc., U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, General Principles of Law of the Sea, 97 Int’l L. Stud. 27, 35 (2021) [hereinafter General Principles of Law of the Sea].

50. See UNCLOS, supra note 30, pt. II, art. 18.

51. Id.

52. Id. pt. II, art. 19 (providing a list of activities that violate innocent passage).

53. See General Principles of Law of the Sea, supra note 49, at 32-36.

54. See UNCLOS, supra note 30, pt. II, art. 33, pt. III, art 58, pt. VII, art. 87.

55. Id. pt. VI, art. 76.

56. See id. art. 76(3) (“The continental margin comprises the submerged prolongation of the land mass of the coastal [s]tate, and consists of the seabed and subsoil of the shelf, the slope and the rise. It does not include the deep ocean floor with its oceanic ridges or the subsoil thereof.”).

57. Id. pt. VI, art. 77.

58. Id. pt. VIII, art. 121, ¶¶ 1, 3.

59. Id. pt. VIII, art. 121, ¶ 2.

60. Id. pt. VIII, art. 121, ¶ 3.

61. Id.

62. Id. pt. II, art. 13.

63. See id.

64. Id. pt. V, art. 60, ¶ 1.

65. Id. pt. V, art. 60, ¶ 8.

66. Id. pt. V, art. 60, ¶¶ 4, 5.

67. U.S. Dep’t of Def., Annual Freedom of Navigation Report 2 (2022) [hereinafter 2022 Freedom of Navigation Report].

68. See id.

69. Id.

70. Id.

71. Id.

72. Id.

73. E.g., France, UK Announce South China Sea Freedom of Navigation Operations, NavalToday.com (June 6, 2018), https://www.navaltoday.com/2018/06/06/france-uk-announce-south-china-sea-freedom-of-navigation-operations.

74. See 2022 Freedom of Navigation Report, supra note 67, at 5 (identifying China’s excessive maritime claims that U.S. forces operationally challenged over the last fiscal year).

75. See Michael Wood (Special Rapporteur), Second Rep. on Identification of Customary International Law, U.N. Doc. A/CN.4/672, at 23 (May 22, 2014) (noting that the “passage of ships in international waterways” is an action identified as “[p]hysical action of [s]tates” evidencing customary international law).

76. See, e.g., 2022 Freedom of Navigation Report, supra note 67, at 5 (listing excessive maritime claim against China asserting “[i]mplied claim to territorial sea and airspace around features not so entitled (i.e., low-tide elevations)”).

77. The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea is an independent judicial body that has jurisdiction over any dispute concerning the interpretation or application of UNCLOS. See Int’l Tribunal for L. of Sea, https://www.itlos.org/en/main/latest-news (last visited Dec. 6, 2023). It is not, however, the only means to which contracting parties can resolve UNCLOS-related disputes. Contracting parties can also resolve disputes through the International Court of Justice or through arbitration. See UNCLOS, supra note 30, pt. XV, art. 287.

78. The authority regulates all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area. See International Seabed Authority, https://www.isa.org.jm (last visited Dec. 6, 2023).

79. See UNCLOS, supra note 30, annex VI (the Tribunal), pt. XI, art. 156 (the Authority), and annex II (the Commission).

80. See Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, U.N. Div. for Ocean Affs. & L. of Sea, https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/clcs_home.htm (last visited Dec. 6, 2023).

81. UNCLOS, supra note 30, annex II, art. 4.

82. Id. annex II, art. 2, ¶ 1.

83. Id.

84. See id. annex II, art. 3.

85. Id. pt. VI, art. 76, ¶ 8.

86. Id. annex II, art. 9.

87. Executive Summary, Joint Submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf Pursuant to Article 76, Paragraph 8 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 in Respect of the Southern Part of the South China Sea (May 2009) [hereinafter 2009 Malaysia-Vietnam Joint Submission], https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/mys_vnm2009excutivesummary.pdf.

88. Executive Summary, Partial Submission in Respect of Vietnam’s Extended Continental Shelf: North Area (VNM-N) (May 2009) [hereinafter 2009 Vietnam Partial Submission], https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/vnm37_09/vnm2009n_executivesummary.pdf.

89. Executive Summary, Malaysia Partial Submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf Pursuant to Article 76, Paragraph 8 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 in the South China Sea (Nov. 2017) [hereinafter 2019 Malaysia Partial Submission], https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mys85_2019/20171128_MYS_ES_DOC_001_secured.pdf. While dated November 2017, Malaysia submitted the document to the UN on 12 December 2019. Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf Beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Baselines: Submissions to the Commission: Partial Submission by Malaysia in the South China Sea, U.N. Div. for Ocean Affs. & L. of Sea (July 25, 2022), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_mys_12_12_2019.html.

90. See supra note 86 and accompanying text.

91. See 2009 Malaysia-Vietnam Joint Submission, supra note 87, at 3; 2009 Vietnam Partial Submission, supra note 88, at 3.

92. Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. CML/17/2009 (May 7, 2009) [hereinafter CML/17/2009], https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/chn_2009re_mys_vnm_e.pdf; Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. CML/18/2009 (May 7, 2009) [hereinafter CML/18/2009], https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/vnm37_09/chn_2009re_vnm.pdf.

93. CML/17/2009, supra note 92; accord CML/18/2009, supra note 92.

94. CML/17/2009, supra note 92; accord CML/18/2009, supra note 92.

95. For access to all communications in response to the joint submission, see Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS): Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf Beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Baselines: Submissions to the Commission: Joint Submission by Malaysia and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, U.N. Div. for Ocean Affs. & L. of Sea (May 3, 2011), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_mysvnm_33_2009.htm. For access to all communications in response to Vietnam’s partial submission, see Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS): Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf Beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Baselines:Submissions to the Commission: Submission by the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, U.N. Div. for Ocean Afs. & L. of Sea (May 3, 2011), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_vnm_37_2009.htm.

96. Permanent Mission of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. 86/HC-2009 (May 8, 2009), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/vnm_chn_2009re_mys_vnm_e.pdf.

97. Id.

98. Permanent Mission of the Republic of the Philippines to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. 11-00494 (Apr. 5, 2011), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/phl_re_chn_2011.pdf.

99. Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. CML/8/2011, at 1 (Apr. 14, 2011), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/chn_2011_re_phl_e.pdf.

100. Id.

101. Id. at 1-2.

102. Permanent Mission of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. 77/HC-2011 (May 3, 2011), https://www.un.org/Depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/vnm_2011_re_phlchn.pdf.

103. Republic of the Philippines, Dep’t of Foreign Affs., No. 13-0211, Notification and Statement of Claim 23 (Jan. 22, 2013) [hereinafter Notification and Statement of Claim], https://dfa.gov.ph/images/UNCLOS/Notification%20and%20Statement%20of%20Claim%20on%20West%20Philippine%20Sea.pdf. Part XV of UNCLOS provides for two means of dispute resolution, consensual means and compulsory settlement. See UNCLOS, supra note 30, pt. XV. Consensual means can take the form of conciliation, negotiation, or diplomacy. Id. pt. XV, art. 280. Under Article 287, there are four types of compulsory dispute settlement: the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea; the International Court of Justice; arbitration in accordance with UNCLOS Annex VII; or creation of a special arbitration tribunal in accordance with UNCLOS Annex VIII. Id. pt. XV, art. 287. When parties cannot agree on a compulsory form of settlement, Annex VII arbitrations prevail. Id.

104. In the Matter of the South China Sea Arbitration (Phil. v. China), Case No. 2013-19, Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility, ¶ 99 (Perm. Ct. Arb. 2016) [hereinafter South China Sea Arbitration Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility], https://pcacases.com/web/sendAttach/2579.

105. Position Paper of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Matter of Jurisdiction in the South China Sea Arbitration Initiated by the Republic of the Philippines, Ministry of Foreign Affs. of People’s Republic of China ¶ 2 (Dec. 7, 2014), https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/gjhdq_665435/2675_665437/ 2762_663528/2763_663530/201412/ t20141207_520915.html.

106. Id. ¶ 3.

107. UNCLOS, supra note 30, pt. XV, art. 288, ¶ 4.

108. See South China Sea Arbitration Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility, supra note 104.

109. Id.

110. Id. ¶¶ 151-78.

111. Id. ¶ 152.

112. In the Matter of the South China Sea Arbitration (Phil. v. China), Case No. 2013-19, Award, pt. X, ¶ 1203(B)(2) (Perm. Ct. Arb. 2016) [hereinafter South China Sea Arbitration Award], https://pcacases.com/web/sendAttach/2086.

113. See id. pt. X, ¶ 1203(B).

114. Id. pt. X, ¶ 1203(B)(2).

115. See id. pt. VI, ¶¶ 643, 646, pt. X, ¶ 1203(B)(3).

116. See id. pt. VI, ¶ 646.

117. Id. pt. X, ¶¶ 1203(B)(8)-(15).

118. Statement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China on the Award of 12 July 2016 of the Arbitral Tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration Established at the Request of the Republic of the Philippines, Embassy of People’s Republic of China in the United Arab Emirates (July 12, 2016), http://ae.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/xwdt/201607/t20160712_1036800.htm.

119. China Adheres to the Position of Settling Through Negotiation the Relevant Disputes Between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea, State Council: People’s Republic of China para. 70 (July 13, 2016), http://english.www.gov.cn/state_council/ministries/2016/07/13/content_281475392503075.htm.

120. There are numerous analyses on Chinese compliance with the award. See, e.g., Sourabh Gupta, The South China Sea Arbitration Award Five Years Later, Lawfare (Aug. 3, 2021, 2:42 PM), https://www.lawfareblog.com/south-china-sea-arbitration-award-five-years-later; Failing or Incomplete? Grading the South China Sea Arbitration, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (July 11, 2019), https://amti.csis.org/failing-or-incomplete-grading-the-south-china-sea-arbitration.

121. 2019 Malaysia Partial Submission, supra note 89.

122. Id.

123. Id. pt. I, ¶ 4.1.

124. For access to all communications in response to Malaysia’s partial submission, see Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS): Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf Beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Baselines: Submissions to the Commission: Partial Submission by Malaysia in the South China Sea, U.N. Div. for Ocean Affs. & L. of Sea (July 25, 2022) [hereinafter Partial Submission by Malaysia Submissions], https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_mys_12_12_2019.html.

125. Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. CML/14/2019 (Dec. 12, 2019), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mys85_2019/CML_14_2019_E.pdf.

126. Permanent Mission of the Republic of the Philippines to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. 000191 (Mar. 6, 2020), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mys_12_12_2019/2020_03_06_PHL_NV_UN_001.pdf.

127. Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. CML/11/2020 (Mar. 23, 2020), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mys_12_12_2019/China_Philippines_ENG.pdf.

128. Permanent Mission of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. 22/HC-2020 (Mar. 30, 2020), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mys_12_12_2019/VN20200330_ENG.pdf.

129. Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to U.N., Note Verbale to the U.N. Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. CML/42/2020 (Apr. 17, 2020), https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mys_12_12_2019/2020_04_17_CHN_NV_UN_003_EN.pdf.

130. Partial Submission by Malaysia Submissions, supra note 124.

131. See generally id.

132. Permanent Rep. of U.S. to U.N., Letter dated 1 June 2020 from the Permanent Representative of the United States to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. A/74/874 (June 2, 2020), https://undocs.org/a/74/874.

133. Press Release, Michael R. Pompeo, U.S. Sec’y of State, U.S. Position on Maritime Claims in the South China Sea (July 13, 2020), https://2017-2021.state.gov/u-s-position-on-maritime-claims-in-the-south-china-sea/index.html.

134. Id.

135. Id.

136. See Blinken, supra note 18.

137. See Partial Submission by Malaysia Submissions, supra note 124.

138. See id.

139. Permanent Rep. of China to U.N., Letter dated 9 June 2020 from the Permanent Representative of China to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. A/74/886 (June 10, 2020), https://undocs.org/en/a/74/886.

140. Id. annex, para. II.

141. Karen Leigh et al., Troubled Waters: Where the U.S. and China Could Clash in the South China Sea, Bloomberg (Dec. 17, 2020), https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2020-south-china-sea-miscalculation.

142. O’Rourke, supra note 9, at 12.

143. Dolven et al., supra note 4, at 1.

144. See supra note 93 and accompanying text.

145. See O’Rourke, supra note 9, tbls.2, 3 at 32-35; see also DoD Annual Freedom of Navigation (FON) Reports, U.S. Dep’t of Def., https://policy.defense.gov/OUSDP-Offices/FON (last visited Dec. 11, 2023) (providing, by fiscal year, a report of all operational challenges).

146. O’Rourke, supra note 9, at 38.

147. Robert Beckman, The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Maritime Disputes in the South China Sea, 107 Am. J. Int’l L. 142, 144 (2013).

148. Paracel Islands, World Factbook (Nov. 14, 2023), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/paracel-islands.

149. Id.

150. Stein Tønnesson, Why Are the Disputes in the South China Sea So Intractable? A Historical Approach, 30 Asian J. Soc. Sci. 570, 574 (2002).

151. Id.

152. Paracel Islands, supra note 148. The following is a list of all features where China has an outpost: “Antelope, Bombay, and North reefs; Drummond, Duncan, Lincoln, Middle, Money, North, Pattle, Quanfu, Robert, South, Tree, Triton, Woody, and Yagong islands; South Sand and West Sand; Observation Bank.” Id.

153. See Island Features of the South China Sea, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/scs-features-map (last visited Dec. 11, 2023) (providing an interactive map that shows what entities claim or occupy the various features in the South China Sea).

154. Paracel Islands, supra note 148.

155. See Update: China’s Continuing Reclamation in the Paracels, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (Aug. 9, 2017), https://amti.csis.org/paracels-beijings-other-buildup.

156. Beckman, supra note 147, at 143.

157. Spratly Islands, World Factbook (Nov. 14, 2023), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/spratly-islands.

158. Id.

159. Id.

160. Id.

161. See China Island Tracker, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/island-tracker/china (last visited Dec. 11, 2023) (providing a complete list of all Chinese-occupied features in the South China Sea: Cuarteron, Fiery Cross, Gaven, Hughes, Johnson, Mischief, and Subi reefs).

162. U.S. Dep’t of Def., Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 102 (2020) [hereinafter 2020 China Military Power Report].

163. See U.S. Dep’t of Def., The Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy 16 (2015) [hereinafter 2015 Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy].

164. Id.

165. 2020 China Military Power Report, supra note 162, at 102.

166. Jeremy Page et al., China’s President Pledges No Militarization in Disputed Islands, Wall Street J. (Sept. 25, 2015), https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-completes-runway-on-artificial-island-in-south-china-sea-1443184818.

167. See Comparing Aerial and Satellite Images of China’s Spratly Outposts, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (Feb. 16, 2018), https://amti.csis.org/comparing-aerial-satellite-images-chinas-spratly-outposts.

168. Id.

169. U.S. Dep’t of Def., Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 12 (2017) [hereinafter 2017 China Military Power Report].

170. U.S. Dep’t of Def., Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 124 (2023) [hereinafter 2023 China Military Power Report].

171. Id. at 85.

172. Comparing Aerial and Satellite Images of China’s Spratly Outposts, supra note 167; see also U.S. Admiral Says China Has Fully Militarized Islands, Politico (Mar. 20, 2022, 3:25 PM), https://www.politico.com/news/2022/03/20/china-islands-militarized-missiles-00018737.

173. 2021 China Military Power Report, supra note 11, at 104.

174. Id.

175. See Itu Aba Island, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/itu-aba-island (last visited Dec. 18, 2023).

176. Taiping Island: An Island or a Rock Under UNCLOS, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (May 7, 2015), https://amti.csis.org/taiping-island-an-island-or-a-rock-under-unclos/.

177. Steven Lee Myers, Island or Rock? Taiwan Defends Its Claim in South China Sea, N.Y. Times (May 20, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/20/world/asia/china-taiwan-island-south-sea.html.

178. South China Sea Arbitration Award, supra note 112, para. 626, at 254.

179. Myers, supra note 177.

180. See Vietnam Island Tracker, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/island-tracker/vietnam (last visited Dec. 18, 2023) (providing a complete list of all Vietnam-occupied features in the South China Sea; noting that Vietnam constructed multiple outposts on single reefs or banks, leading to confusion about how many features it actually occupies; and noting that the status of two construction projects on Cornwallis South Reef is unclear).

181. Vietnam Shores Up Its Spratly Defenses, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (Feb. 19, 2021), https://amti.csis.org/vietnam-shores-up-its-spratly-defenses; Vietnam Rapidly Builds Up South China Sea Reef, Radio Free Asia (Nov. 6, 2023), https://www.rfa.org/english/news/southchinasea/vietnam-reef-11062023032009.html.

182. See id. The outposts are located at these features: Amboyna Cay, Central Reef, Grierson Reef, Namyit Island, Sand Cay, Sin Cowe Island, Southwest Cay, and West Reef. Id.

183. See Vietnam Island Tracker, supra note 180.

184. See id. The outposts are located at these features: Alison Reef, Barque Canada Reef, Collins Reef, Cornwallis South Reef, Discovery Great Reef, East Reef, Ladd Reef, Landsdowne Reef, Pearson Reef, Petley Reef, South Reef, and Tennent Reef. Id.

185. Vietnam Builds Up Its Remote Outposts, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (Aug. 4, 2017), https://amti.csis.org/vietnam-builds-remote-outposts.

186. See id. The DK1 stations are located at these features: Alexandra Bank, Grainger Bank, Prince Consort Bank, Prince of Wales Bank, Rifleman Bank, and Vanguard Bank. Id.

187. See id. (describing the DK1 structures and their capabilities and providing aerial photographs).

188. See Malaysia Island Tracker, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/island-tracker/malaysia (last visited Dec. 19, 2023) (providing a complete list of all Malaysia occupied features in the South China Sea: Ardasier Reef, Erica Reef, Investigator Shoal, Mariveles Reef, and Swallow Reef).

189. Airpower in the South China Sea, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (July 29, 2015), https://amti.csis.org/airstrips-scs.

190. See Malaysia Island Tracker, supra note 188.

191. See Philippines Island Tracker, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/island-tracker/philippines (last visited Dec. 18, 2023) (providing a complete list of all the Philippines occupied features in the South China Sea: Commodore Reef, Flat Island, Loaita Cay, Loaita Island, Nanshan Island, Northeast Cay, Second Thomas Shoal, Thitu Island, and West York Island).

192. Philippines Launches Spratly Runway Repairs, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (May 25, 2018), https://amti.csis.org/philippines-launches-spratly-repairs; Daily Life on Thitu Island, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative (Dec. 10, 2015), https://amti.csis.org/daily-life-on-thitu-island.

193. Daily Life on Thitu Island, supra note 192.

194. Id.

195. See Thitu Island, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/thitu-island (last visited Dec. 20, 2023).

196. See Philippines Island Tracker, supra note 191.

197. Manuel Mogato, Exclusive: Philippines Reinforcing Rusting Ship on Spratly Reef Outpost, Reuters (July 13, 2015, 5:09 PM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southchinasea-philippines-shoal-exclu/exclusive-philippines-reinforcing-rusting-ship-on-spratly-reef-outpost-sources-idUSKCN0PN2HN20150714.

198. Spratly Islands, supra note 157.

199. See J. Ashley Roach, Malaysia and Brunei: An Analysis of their Claims in the South China Sea 3 (2014) (detailing the dealings between Brunei and Malaysia and their agreements pertaining to their maritime boundaries).

200. Vietnam Builds Up Its Remote Outposts, supra note 185; see Rifleman Bank, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/rifleman-bank (last visited Dec. 18, 2023).

201. See Yoshiyuki Ogasawara, The Pratas Islands: A New Flashpoint in the South China Sea, The Diplomat (Dec. 10, 2020), https://thediplomat.com/2020/12/the-pratas-islands-a-new-flashpoint-in-the-south-china-sea.

202. Id.

203. Keyuan Zou, Introduction to Routledge Handbook of the South China Sea 1 (Keyuan Zou ed., 2021).

204. See Island Features of the South China Sea, supra note 153.

205. See Maritime Claims of the Indo-Pacific, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/maritime-claims-map (last visited Dec. 18, 2023) (displaying that both China and Taiwain claim Macclesfield Bank, which sits just to the left of the “S” in “Sea” on the interactive map).

206. Zou, supra note 203.

207. See Scarborough Shoal, Asia Mar. Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/scarborough-shoal (last visited Dec. 18, 2023).

208. O’Rourke, supra note 9, at 7.

209. Jason Gutierrez, Overwhelmed by Chinese Fleets, Filipino Fisherman ‘Protest and Adapt,’ N.Y. Times (July 11, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/11/world/asia/philippines-south-china-sea-fishermen.html.

210. Id.

211. Id.