(Credit: istockphoto.com Benjavisa)

People First, Including You

The Importance of Self-Care

By Lieutenant Colonel Aimee M. Bateman

Lawyers work hard and, like us, they’re human, many of them.1

In General James C. McConville’s “Initial Message to the Army Team,” the 40th Chief of Staff of the Army signed off with, “People First—Winning Matters—Army Strong!”2 He made it clear that cultivating the human dimension through teambuilding, training, and respect is a “sacred obligation” required for success on the battlefield.3 We may interpret this as saying that we, as leaders, must putother people first. However, it is just as crucial to remember that each and every one of usare people first, before we are Soldiers, officers, attorneys, or leaders. It is a simple fact. Lawyer jokes aside, we are not machines, and we are not impermeable to stress and mental injuries. It is impossible “to build cohesive teams that are highly trained, disciplined, and fit”4 if you do not first take care of yourself. This article will cover the basics of self-care and implore you to be the best example of such, not only for your personal well-being, but for the sake of overall mission readiness. It will also highlight recommendations from “The Path to Lawyer Well-Being:Practical Recommendations for Positive Change,” a report from the National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being.5 Everyone in our Corps is a stakeholder and a leader. This is a call to action for each and every one of you.

The “What” and “Why” of Self-Care

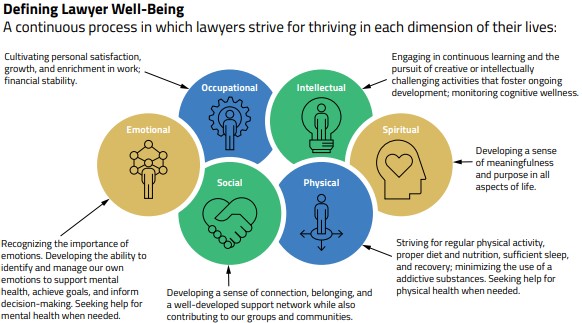

If we take a moment to be honest with ourselves, it is unlikely any one of us is truly a “T”6 in self-care, or can ever be. The National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being (Task Force), defines lawyer well-being as, “[a] continuous process in which lawyers strive for thriving in each dimension of their lives.”7 Unfortunately, many Soldiers and Civilians in our formations merely survive rather than thrive on a daily basis. How many of us in leadership positions are doing the same?

When leaders eschew practicing self-care, it can be disastrous for an organization. A leader who is sleep-deprived, depressed, anxious, or otherwise unwell is much more likely to display what is collectively described as “counterproductive leadership.”8 Such poor leadership includes insulting or belittling individuals; losing temper and being unapproachable; poorly motivating others; and withholding encouragement.9 “Counterproductive leadership behaviors prevent establishing a positive organizational climate and interfere with mission accomplishment, especially in highly complex operational settings.”10 Therefore, we must dispel any misconception that taking the time to take care of yourself when you are in a leadership position is selfish; it is quite the contrary. Whatever short-term gains you might achieve through counterproductive leadership techniques employed in a state of exhaustion and stress will “have a damaging effect on the organization’s performance and subordinate welfare.”11

The “How” of Self-Care

To be clear,this is about the well-being of all legal professionals, even though “the majority of lawyers . . . do not have a mental health or substance use disorder.”12 In addition to diagnosable mental health conditions, low job satisfaction, disengagement, and impaired cognitive functioning prevent lawyers and paralegals from doing their best work. In order to meet the mission and “[p]rovide principled counsel and premier legal services,”13 all judge advocates and paralegals must excel across all domains and dimensions.

Among the myriad resources available, the Task Force’s report, “The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change” (“Report”) is exemplary and will be the focus of the rest of this note.

The graphic from the Task Force’s report further defines lawyer well-being.14

As Army leaders, these dimensions should feel familiar to us. The Army defines “Comprehensive Solider and Family Fitness” through “Five Dimensions of Strength: physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and family.”15 What our regulation fails to capture is the occupational and intellectual dimensions, which are absolutely critical to our psychological health as attorneys and paralegals. Simply being a Soldier is stressful, and our dual profession creates a unique set of circumstances going beyond what most individuals must navigate in order to thrive in all dimensions. Being an attorney frequently means being adversarial; it often means being alone and isolated. In many instances, we succeed by pointing out the mistakes of others and working tirelessly, sometimes relentlessly, to minimize our own.

Our most high-risk personnel are our litigators. The corollary population in the law enforcement community is the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Division Command (CID), which now has a “Wellness Program.” This program “consists of embedded wellness teams within the battalions and the Defense Forensic Science Center (DFSC)).”16 This newly instituted program grew out of the acknowledgement that “repeated exposure to traumatic investigative situations and associated investigative materials can significantly affect psychological well-being, as well as cause strain to family relationships, reduce resilience, and negatively impact readiness.”17

As we implement the Military Justice Redesign (MJR)18 and create dedicated litigation billets, leaders must be aware that any gains in competency achieved through a more specialized practice might quickly deteriorate through psychological strain and injury. As stated in the CID information paper, “Research has shown that cases involving child victims, specifically abuse and child pornography, have a significant impact on psychological functioning either in isolated instances or though repeated exposure. Furthermore, prolonged exposure can have a significant impact on family relationships by way of increased conflict, overprotectiveness, and decreased intimacy.”19 Certainly, this research applies just as much to litigation teams dealing with those same types of cases.

If you are a leader implementing the MJR, I encourage you to talk to the experienced Trial Defense Service and Special Victim litigators at your installation. They can give you a contemporary perspective on the emotional, physical, and psychological strain that comes with being an “untethered trial team” that carries a case from “investigation to trial.”20 During my time as a brigade trial counsel, the relationships I developed with the command teams at the company, battalion, and brigade levels provided a sense of community and balance in my life. Do not sell short the potential effects of removing those who litigate cases for the command from the command. Now more than ever, all leaders must have a plan in place “for minimizing lawyer dysfunction, boosting well-being, and reinforcing the importance of well-being to competence and excellence in practicing law.”21

(Credit: istockphoto.com/Benjavisa)

A Call to Action

[T]o meaningfully reduce lawyer distress, enhance well-being, and change legal culture, all corners of thelegal profession need to prioritize lawyer health and well-being. . . . Each of us shares responsibility for making it happen.22

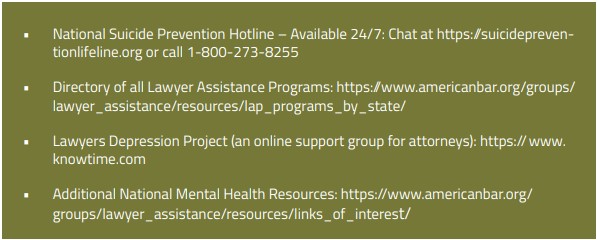

The entire Report of the National Task Force on Lawyer Well-being is a must-read. It provides a roadmap for improving the readiness of your organization through active engagement. A great place to start is the “Recommendations for All Stakeholders” section of the Report.23

Among the thirteen recommendations are:

- Acknowledge the problems and take responsibility.24

- Leaders should demonstrate a personal commitment to well-being.25

- Facilitate, destigmatize, and encourage help-seeking behavior.26

- Build relationships with lawyer well-being experts.27

- Foster collegiality and respectful engagement throughout the profession.28

- Begin a dialogue about suicide prevention.29

Each of these topics lends themselves to their own practice note or leader professional development training. Therefore, I recommend you take the time to read the entire Report, reflect on where you are in your personal journey toward multi-dimensional well-being, and then begin the transformational process within your organization.

Conclusion

Each of us can take a leadership role within our own spheres to change the profession’s mindset from passive denial of problems to proactive support for change. We have the capacity to make a difference.30

I am proud to be part of such an accomplished and resilient community of practice. However, we cannot “outwork” the fact that we are humans. Respect that limitation and use your humanity to your advantage: connect with your clients; show compassion and concern for those you lead; and dare greatly. Be well, and continue this conversation.TAL

LTC Bateman is the Regional Defense Counsel for U.S. Army Trial Defense Service, Great Plains Region, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Notes

1. Dick Cavett, An Innocent Misunderstanding , N.Y. Times Opinionator (Mar. 28, 2007), https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/03/28/an-innocent-misunderstanding/.

2. James C. McConville, 40th Chief of Staff of the Army Initial Message to the Army Team, https://www.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/561506.pdf (last visited Oct. 3, 2019).

3. Id .

4. Id .

5. National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations For Positive Change 9 (Aug. 14, 2017), http://lawyerwellbeing.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Lawyer-Wellbeing-Report.pdf [hereinafter Report ].

6. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Field Manual 7-0, Train to Win in a Complex World para. 1-6 (5 Oct. 2016) (“T is fully trained (complete task proficiency).”).

7. Report, supra note 5.

8. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Doctrine Pub. 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession paras. 8-45–8-50 (31 Jul. 2019).

9. Id. para. 8-49.

10. Id. para. 8-47.

11. Id. para. 8-48.

12. Report , supra note 5, at 7.

13. Leadership – Mission and Vision , The U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) Corps (Mar. 9, 2012), https://www.jagcnet.army.mil/Sites/jagc.nsf/homeContent.xsp?open&documentId=DEE613DFEC84B73B852579BC006142CE#.

14. Report , supra note 5, at 9.

15. U.S. Dep’t of Army, Reg. 350-53, Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness para. 2-1 (18 June 2014).

16. U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Div. Command, Information Paper, Subject: CIDC Wellness Program para. 2 (11 Jun. 2019) (on file with author) [hereinafter Information Paper ).

17. Id . para. 3.b.

18. Major General Stuart W. Risch et al., FOUNDATION SENDS: A Message from The Judge Advocate General and the Leadership Team—The Military Justice Redesign ( July 29, 2019), https://www.jagcnet2.army.mil/Sites/jagc.nsf/xsp/.ibmmodres/domino/OpenAttachment/Sites/JAGC.nsf/8C0BDA8022E3B34B852584460043D402/Attachments/1_Foundation_Sends_MJR.pdf (hereinafter R isch et al. ).

19. Information Paper , supra note 16, para. 3.b.

20. Risch et al. , supra note 18.

21. Report , supra note 5, at 11.

22. Id. at 12.

23. Id. at 12-21.

24. Report , supra note 5, at 12.

25. Id .

26. Id. at 13.

27. Id .

28. Report , supra note 5, at 15.

29. Id. at 20.

30. Id. at 12.