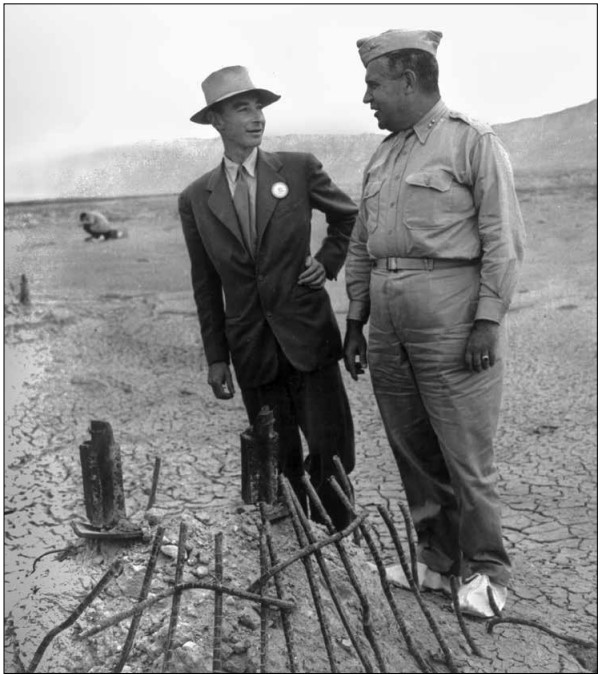

J. Robert Oppenheimer, left , credited with being the “father” of the atomic bomb, stands with then-Major General Leslie R. Groves at the Trinity test site in New Mexico. Groves was the director of the Manhattan Project. The Trinity test was the first test of an atomic bomb. (Courtesy: Atomic Heritage Foundation)

Lore of the Corps

An Army Lawyer and the A-Bomb

By Fred L. Borch III

As 2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, it is time to reflect on the weapon that ended that war and changed the world forever: the atomic bomb. While Americans today and everyone living on this planet have learned to live with—if not ignore—the existence of nuclear weapons, it was truly a shocking event for many adults when the United States dropped the fission bomb “Little Boy” on Hiroshima on 5 August 1945. The devastation wrought by the 8,000-pound bomb—in the form of a mushroom-shaped fireball emitting radiation and heat rays—reduced thousands of buildings to ashes and ultimately killed thousands and thousands of men, women, and children. When a B-29 dropped “Fat Man” on Nagasaki four days later, the power of atomic weapons was evident to all, and the Japanese surrendered.1

While mostly forgotten today, producing this new weapon had been a prodigious undertaking. Major General Leslie R. Groves, who had already achieved fame in overseeing the construction of the Pentagon in just sixteen months, was in charge of all atomic bomb production efforts. Ultimately, Groves coordinated the efforts of factories, laboratories, and mines in thirty-nine states, Africa, and Canada.2 Code-named the Manhattan Project , all basic bomb design and assembly took place at Los Alamos, New Mexico, under the leadership of physicist Robert J. Oppenheimer. A second—and no less important— Manhattan Project site was at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.3 At this location, scientists worked on obtaining the uranium isotope 235 (U235) necessary to build a bomb. The theory was that enormous amounts of energy would be released with the fission (splitting) of the nuclei of U235.4 Consequently, building a device with as little as ten pounds of U235 could deliver explosive power equivalent to several thousand tons of dynamite.5

No one could be certain that these ideas about splitting an atom would really work, much less that nuclear fission could be controlled. In fact, some scientists believed that “the first atom to be split would ignite a chain reaction that would consume the entire universe.”6 In any event, from the time President Roosevelt approved a super-secret crash program to build atomic bombs in the summer of 1941, until August 1945, when the two bombs detonated, some 600,000 men and women worked in some way with the Manhattan Project at a cost of an unprecedented $2 billion.7 This made the project the most sophisticated large-scale effort ever undertaken in human history. By comparison, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote that the Great Pyramid required 100,000 men working for twenty years, and the building of the Great Wall of China may have involved 1,000,000 men.8

Among these thousands of Manhattan Project workers was at least one judge advocate, First Lieutenant (1LT) Philip J. Close. A graduate of the University of Chicago Law School, Close had been a trial lawyer in a law firm in Kansas City, Missouri, from 1934 to January 1944, when he was drafted into the Army at the age of thirty-two. After basic training, Close qualified as a military policeman. He completed eight weeks of training in military government at the Provost Marshal General’s School at Fort Custer, Michigan, and was promoted to corporal (CPL) in September 1944.9

Realizing that he preferred to use his skills as a lawyer in the Army, CPL Close decided to apply to Officer Candidate School (OCS) at The Judge Advocate General’s School, then located on the campus of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. After being informed that the application process was highly competitive, CPL Close looked for ways to enhance his chances of success. He wrote to the senior partner in his old law firm in Kansas City and, through the senior partner, obtained the support of politicians in the area, including then-Senator Harry S. Truman. Whether this political support was the deciding factor will never be known, but when CPL Close submitted his application for OCS, it was accepted.10 He subsequently completed the seventeen-week OCS and basic military law course of instruction and commissioned as a second lieutenant, Judge Advocate General’s Department, on 11 January 1945.

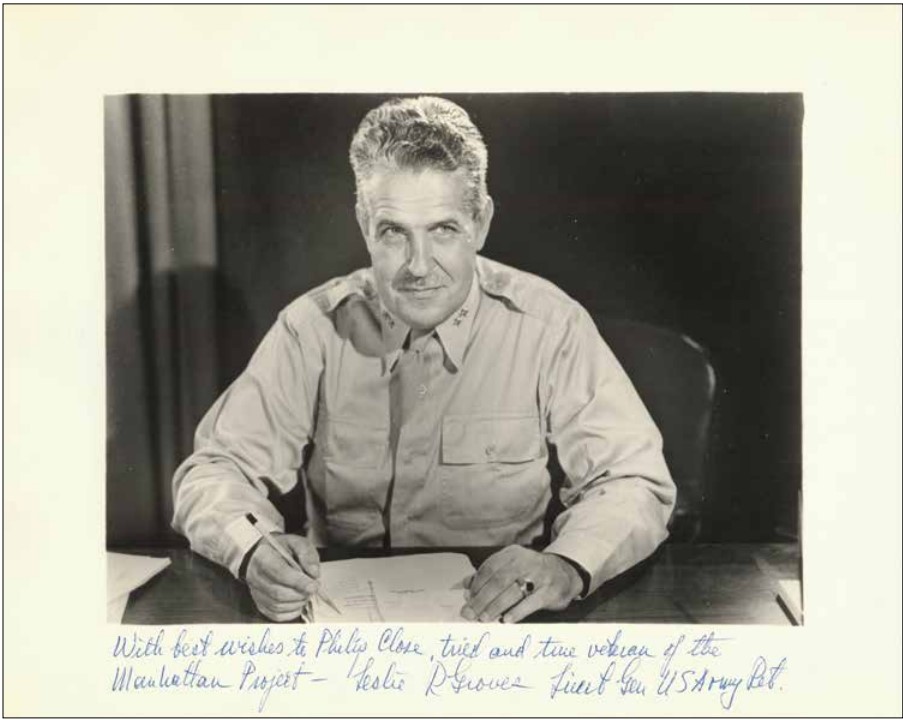

Close reported to the Manhattan Engineer District, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where he assumed duties as the “Staff Judge Advocate to the Commanding Officer.”11 According to his military records, in his eleven months of service in that position, Close “supervised and handled all matters of military justice for the command,” and he also provided legal assistance and served as a claims officer.”12 First Lieutenant Close certainly had an excellent relationship with his boss, then-Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, as evidenced by the inscription from Groves on a photograph given to him. “With best wishes to Philip Close, tried and true veteran of the Manhattan Project.”13

Philip Close served honorably and faithfully, but he was profoundly affected by the Manhattan Project and the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He expressed his heartfelt feelings in a letter written to his parents on 9 August 1945—the day the second bomb destroyed Nagasaki. The letter is worth setting out at some length because it captures what more than a few Americans thought at the time.

Close begins his letter by telling his parents that he and a more senior judge advocate stationed in New York have “really been sitting on a keg of dynamite, or much worse, anticipating the claims and litigation that might result” from the testing of the atomic bomb at Alamogordo on 16 July 1945.14 “Under considerable pressure,” he continues, “I [also] prepared the legislative recommendations that will serve as an initial start toward congressional action to preserve and control the use of atomic energy. Rumor has already indicated that a board would be appointed to produce and control it.”15 According to 1LT Close, he had “to grind out” his legal work “in haste before the impact and real significance of the discovery became apparent.”16 By this “impact and real significance,” Philip Close almost certainly means the events of 5 and 9 August 1945.17

A signed photograph of General Leslie R. Groves. The inscription reads, “With best wishes to Philip Close, tried and true veteran of the Manhattan Project – Leslie R. Groves, Lieut Gen US Army Ret.” (Courtesy: Fred Borch, Regimental Historian)

In the remainder of his letter to his parents, then-thirty-three-year-old Close expresses his deepest feelings about this new weapon. When one remembers that the highly classified nature of the Manhattan Project meant that 1LT Close was unable to write even one word to his parents about the work being done at Oak Ridge, the words and phrases in his letter take on a special meaning. Additionally, the letter is an important window into the zeitgeist of the day because it reflects how an Army lawyer who had been part of the Manhattan Project understood that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a watershed event in history.

As you say in your [earlier] letter [to me], it is an awesome, awful, terrible thing. I say without exaggeration that man has reached or is shortly within reach of the point where all earthly civilization can be obliterated. This is considerable cause for sober thought. Sadly enough, there are only a comparative handful of people in the world who realize this or are stunned with it. History is enough teaching and basis for the realization that if we can do it others can. I draw hope from the fact that it may make war too horrible to contemplate and too ridiculous to be engaged in.

[Author’s note: While the United States had a monopoly on nuclear weapons technology in 1945, 1LT Close’s “if we can do it others can” foreshadows the Soviet Union’s development of an atomic weapons program in the 1940s and 1950s.]

I am impressed but not elated. I am relieved but not enthused. My relief stems from the fact that Providence has permitted us to accomplish a goal which if sooner reached by our enemies would in fact have obliterated the nation. I am not given to exaggeration but I say with due deliberation that it is the greatest discovery of all time. There is no basis for comparison with any other discovery of man.

The destructive power of a mere pinch, or spoonful, produces for thousands of feet, violent and recurring explosions in chain fashion, searing heat, and electrically or electronically charged air which kills and disintegrates all in its path. The ground becomes molten, like lava, and drives with a glaze of porcelain or glass. The air remains charged with electricity (for how long after, we, or at least I, do not know), so that the place or site of explosion remains uninhabitable.

[Author’s note: When 1LT Close writes of “electricity,” he means “radiation.” At the time, no one understood the impact of radiation on the environment, much less upon human beings].

It seems quite unreal to be telling you of it, as I have had it locked in my mind for so many months, disclosure of the least bit of information having been heretofore punishable by court-martial. Among other things, I have been the Military Justice Officer for the whole district, entrusted with initiating and recommending courts-martial. The pressure of this secrecy, in addition to the pressure of work, have weighed upon us heavily to the point of near mental exhaustion at times.

[Author’s note: The secrecy surrounding the Manhattan Project was so great that even Vice President Harry S. Truman did not know about the efforts to build the atomic bomb until President Roosevelt was dead and Truman, now the Chief Executive, had a “need to know.”]18

Nagasaki has this morning disappeared from the map. Buildings and people in the immediate vicinity are not blown to bits but disintegrate and vaporize, if you can imagine such a thing. On the outer extremities, all living tissue and material, organic and inorganic, is seared to destruction beyond recognition.

[Author’s note: Over 100,000 died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Temperatures at ground zero reached 5,400 degrees Fahrenheit; most structures were destroyed by fire or blast. At Hiroshima, for example, all but 6,000 of the city’s 76,000 buildings disappeared.]19

. . . .

Unquestionably Japan will surrender or be destroyed. Also, unquestionably, Russia’s abrupt entry into the war was in my opinion solely due to the atomic bomb. It would not normally have occurred so soon. I can visualize Truman telling the others at Potsdam what he could and would do and I can visualize Stalin, a cold clear thinker, pooh-pooh-ing the statement as fantastic and saying he would wait and see. He needed no further sales talk after Monday August 6th.

[Author’s note: Today, there is much historical controversy over the reasons for the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan; Philip Close’s belief that Stalin took action “solely due to the atomic bomb” is inaccurate. Additionally, scholars today know that Stalin knew about the Manhattan Project long before he met with Truman and Churchill at Potsdam.]20

I say to you Mother and Dad that you have never known me to go on so, at great length. I am shaken by the whole thing, not impulsively or inconsiderately, but intelligently and reasoningly, and this three days after the original disclosure. It is not a mere event in a war but it is an epoch, the ultimate results of which we cannot now foresee or predict. It may, and I hope will, be soon turned to constructive good rather than destructive evil. I am endeavoring to translate my thought to you and convey an appreciation of its significance.

. . . .

But now I want to come home. I want to be home and stay home. I want to enjoy my family. I want to do and enjoy simple things in a normal, simple fashion.

Your loving son, Phil21

First Lieutenant Close was not alone in his feelings about the atomic bomb and the danger that nuclear weapons posed to humanity. As the world nears the seventy-fifth anniversary of the end of World War II, and seventy-five years since an atomic weapon was last used in war, much of the fear has dissipated with the passage of time. In fact, as early as the 1960s, Americans were able to satirize, if not laugh, about nuclear war. Actors Peter Sellers, Slim Pickens, and George C. Scott (who would later achieve fame in Patton ) starred in Stanley Kubrick’s “political satire black comedy film” Dr. Strang elove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb , which made fun of Cold War fears of nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union.22 The actual title of the movie says it all. The movie was released in 1964 and received rave reviews from both critics and the public; popular film critic Roger Ebert called it “arguably the best political satire of this century.”23 Yet not even twenty years had passed since judge advocate Phil Close had written his poignant letter to his parents in which he expressed deep-seated fears about the future.

As we enter the third decade of the twenty-first century, 1LT Philip Close’s experiences as a judge advocate in the Manhattan Project are worth reading about, even though he and most likely all of those men and women who were part of this human endeavor have died. As for Close, he was honorably discharged from active duty on 29 December 1945 at Fort McPherson, Georgia. He then returned to Kansas City, Missouri, where he again took up the practice of civilian law. Philip J. Close died in 1963 at the age of 52.24 TAL

Mr. Borch is the Regimental Historian, Archivist, and Professor of Legal History and Leadership.

Notes

* The author thanks Ms. Janet Close Ewert for her help in preparing this article about her father.

1. “Little Man” referred to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Oxford Companion to the Second World War 530, 773 (I.C.B. Dear et al. eds., 1995) [ hereinafter Oxford Companion] . “Fat Man,” the nickname given to the second atomic bomb, referred to Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Id.

2. Patrick Feng, Lieutenant General Leslie R. Groves, Jr. , On Point, Spring 2016, at 18.

3. While Los Alamos and Oak Ridge arguably were the most important Manhattan Project locations, engineers and scientists in the United States also worked on the atomic bomb at Berkeley (California), Hanford (Washington), Milwaukee (Wisconsin), Detroit (Michigan), Chicago and Decatur (Illinois), and New York (New York). For more on the project, see Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1986).

4. Oxford Companion, supra note 1, at 773.

5. Id.

6. Don Demark, Manhattan Project , in Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Army 296 (2001).

7. Oxford Companion, supra note 1, at 773.

8. Id .

9. War Department, Adjutant General’s Office Form No. 55, Enlisted Record of Philip J. Close, 11 January 1945.

10. Interview with Ms. Janet Close Ewert, 1LT Close’s daughter (Sept. 18, 2019) [hereinafter Ewert Interview].

11. War Department, Adjutant General’s Office Form 100, Separation Qualification Record, Philip J. Close.

12. Id.

13. Id.

14. Letter from Philip J. Close to Mr. and Mrs. Close (9 Aug. 1945) (on file with author).

15. Id.

16. Id.

17. Id.

18. David McCullough, Truman 377-78 (1992).

19. Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan 477 (2008).

20. Id . at 445-47, 480-81, 488.

21. Hastings, supra note 19.

22. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0057012/ (last visited Oct. 2, 2019).

23. Dr. Strangelove, RogerEbert.com, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-dr-strangelove-1964 (last visited Oct. 2, 2019).

24. Ewert Interview, supra note 10.